This is another way of asking, how long have people been celebrating April Fool's Day?

The earliest unambiguous reference that is currently known is found in a poem by the Flemish writer Eduard De Dene, published in 1561 (more details below). So we can say that April Fool's Day has existed since at least the mid-sixteenth centuy.

However, some other possible earlier references have been suggested. These earlier possibilities are problematic, but let's review them.

Chaucer

Within the past decade, an argument has gained popularity online claiming that Chaucer alluded to April Fool's Day in

The Canterbury Tales, completed circa 1392. If true, it would be the first time the celebration was mentioned in any language. In fact, it would predate any other reference by a good margin.

Geoffrey Chaucer

The claim derives from a line in the

Nun's Priest's Tale which describes the tale as taking place "Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two" (i.e. 32 days since March began). This would place it on either April 1 or 2.

Coupled with the fact that the tale involves trickery (a fox fooling a rooster, and then getting fooled back), this suggests that Chaucer (so the argument goes) purposefully set the tale on April 1 as an allusion to April Fool's Day.

The argument seems sound, until one considers that four lines later Chaucer goes on to tell us that the tale takes place when the sun "in the signe of Taurus had y-runne / Twenty degrees and one, and somewhat more."

If the sun is in the sign of Taurus (which it is from April 20 to May 21), as Chaucer specifically says it is, how could the tale possibly be set on April 1? The two dates contradict each other.

Many Chaucer scholars resolve this contradiction by arguing that the phrase "syn March bigan" may have been a typo by a medieval scribe, and that Chaucer intended to write "syn March was gone," since if we count 32 days from the end of March, we arrive at May 2 or 3, in the sign of Taurus.

But let's assume that Chaucer did set the

Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1, and that he intended this to be a reference to April Fool's Day. We then would have to explain why there's a complete absence of references to the custom of April foolery in the English literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. There's nothing in the plays of the period — no mention of the day in Shakespeare. Nor is it ever referred to in diaries or letters.

It's not until the late 17th century that we find the first unambiguous English-language references to April Fool's Day. Francis Osborne, in his

Deductions from the History of the Earl of Essex (published in 1659), mentions the "impertinent errands, as the Dutch youth do [put upon] fools on the second of April." And John Aubrey, in his

Remains of Gentilism and Judaism (published in 1686), notes the existence of "Fooles holy day. We observe it on ye first of April. And so it is kept in Germany everywhere."

Both these writers associated the tradition of April Fool's Day with foreign countries (Netherlands and Germany). And Osborne didn't seem very familiar with the custom, given that he thought it was celebrated on the second of April, not the first.

So if English writers of the late seventeenth century believed that April Fool's Day was a foreign custom, it's difficult to understand why Chaucer, writing almost 300 years before, would have known about it. And even if he did somehow know about it, why would he have assumed that his English readers also were familiar with it.

In fact, the evidence suggests that Chaucer had no knowledge of April Fool's Day and therefore couldn't have intended to allude to it. Nor, in all likelihood, did he even intend to set the

Nun's Priest's Tale on April 1.

Note: I examine the Chaucer/April Fool controversy in more detail elsewhere.

Poisson d'Avril

The French term for 'April Fool' is 'poisson d'Avril.' It translates literally as 'April Fish.'

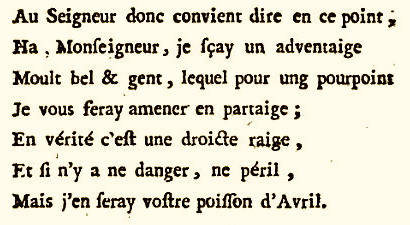

The term appears in several late-medieval French poems — first in the work of

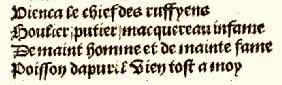

Pierre Michault (1466) and next in

La Livre de la Deablerie (1508), by Eloy d'Amerval. This has led some to suggest, quite reasonably, that these may be early April Fool's Day references.

However, etymologists believe that the phrase 'poisson d'Avril' originally referred to a matchmaker, or to someone who delivered messages between two lovers. It was only in the late 17th century that the phrase acquired its modern association with April Fool's Day.

And if we examine these late-medieval poems, we see that this is the case. For example, Michault's poem describes the advice being given to a page, who is being told how to deliver messages between a lord and lady to further their illicit affair, and how to do this to his own advantage. Michault writes:

Now you should say to the Lord, ah, sir, I know of a fine and pleasing advantage, by which for a doublet I shall bring you together; truthfully, carnal love is a proper desire, and thus there is no danger or peril, but still, I shall be your 'poisson d'avril'.

There's no indication that this has anything to do with April Fool's Day.

Likewise, d'Amerval wrote, "le chief des ruffyens, Houlier, putier, macquereau infame De maint homme et de mainte fame, Poisson d'Apvril." Loosely translated, this means something like, "chief ruffian, whore-monger, pimp of many a man and many a woman, panderer (April fish)." The way d'Amerval is using the phrase doesn't suggest any connection with April Fool's Day.

Therefore, these early uses of the phrase 'poisson d'Avril,' although intriguing, do not appear to be references to April Fool's Day.

Verzenderkensdag

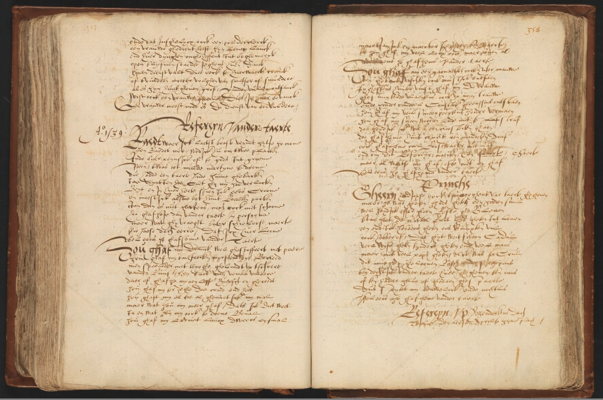

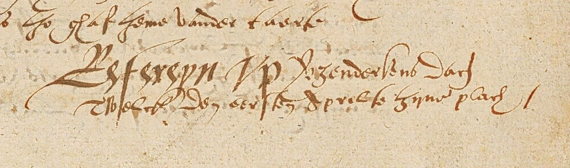

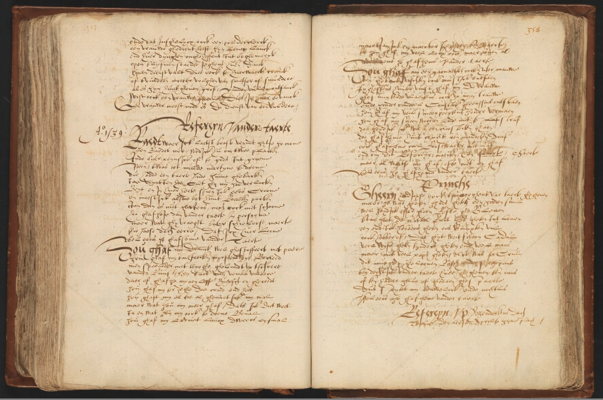

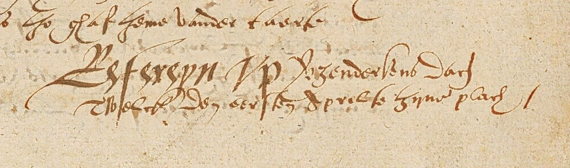

In 1561, the Flemish poet Eduard De Dene, who lived in the city of Bruges, published his

Testament Rhetoricael. The book consisted of a large collection of poems and songs, and 'published' is perhaps not the right word to describe its debut, since it was entirely handwritten. But on page 358, the book included a poem titled "Refereyn vp verzendekens dach / Twelck den eersten April te zyne plach." This is late-medieval Dutch meaning (approximately) "Refrain on fool's errand-day / which is the first of April." The poem described a nobleman who sent his servant back and forth on various absurd errands on April 1st, ostensibly to help prepare for a wedding feast.

De Dene's

Testament Rhetoricael, page 358.

The 'April Fool' poem begins on the bottom of the right-hand page. (Detail below)

There's no doubt that the poem is about April Fool's Day. In fact, in Belgium April 1 is still referred to as "Verzenderkensdag".

So this poem is the earliest unambiguous reference to April Fool's Day that we currently know of. Its existence establishes that the Dutch have been playing pranks on April 1 since at least the mid-sixteenth century.

Given that De Dene assumes his readers are familiar with "verzendekens dach," it's probable that the custom is much older than the 1560s. But exactly how much older, we don't know.

Comments