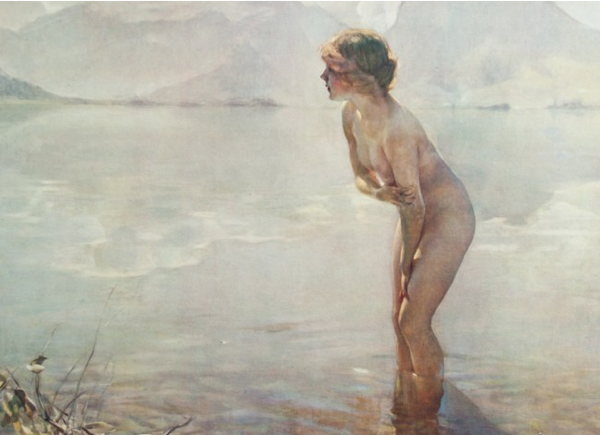

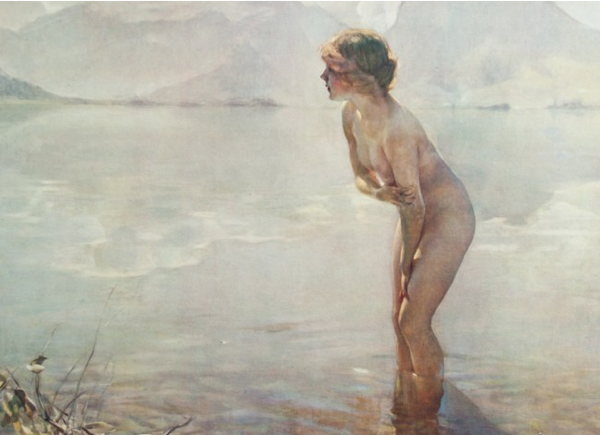

The French painter Paul Chabas completed "September Morn" in early 1912. The painting shows a young woman demurely bathing nude by the edge of Lake Annecy in Haute-Savoie, France. When Chabas showed it that year at the Paris Salon, it won a gold medal of honor. Critics praised it. But when copies of the painting made their way to America, it provoked a bitter controversy there about nudity, art, and public morality. Thanks to this controversy, September Morn became one of the most famous and popular paintings of the twentieth century. It sold millions of copies and was reproduced on a wide variety of merchandise including umbrellas, suspenders, postcards, candy boxes, cane heads, and watch fobs.

September Morn, by Paul Chabas

But in an ironic twist to the September Morn story, the publicist Harry Reichenbach later claimed to have started the controversy by complaining to moral censors about the indecency of the painting. He didn't actually feel the painting was indecent. He was cynically manipulating the self-righteous moralists in order to sell copies of the painting. It was an early example of a marketer staging a phony protest for the sake of publicity -- aka "success by scandal."

The story of how Reichenbach made September Morn the most popular painting in the world has been frequently repeated in books, newspapers, and magazines. It's considered one of the classic tales of clever, though unscrupulous, marketing. But an examination of the chronology of events during the controversy reveals that Reichenbach couldn't have played the role he claimed. He apparently invented the tale of his stunt in order to embellish his reputation as a master salesman.

Reichenbach's Version of Events

According to Reichenbach, he was working for a New York City art dealer in 1913. The dealer had acquired 2000 copies of

September Morn and needed to sell them, so he asked Reichenbach to help. Reichenbach hit upon the idea of generating controversy by calling the painting to the attention of Anthony Comstock, a self-proclaimed moral censor and secretary of an organization called the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. In his autobiography,

Phantom Fame, written with the help of David Freedman and published in 1931, Reichenbach recalled the stunt:

I applied for work at a small art shop that had printed a lithograph of a nude girl standing in a quiet pool. The picture sold at ten cents apiece but nobody would buy it. I could earn my month’s rent if I had an idea for disposing of the two thousand copies in stock. It occurred to me to introduce the immodest young maiden to Anthony Comstock, head of the Anti-Vice Society and arch-angel of virtue. At first he refused to jump at the opportunity to be shocked. I telephoned him several times, protesting against a large display of the picture which I myself had installed in the window of the art shop. Then I arranged for other people to protest and at last I visited him personally. "This picture is an outrage!" I cried. "It's undermining the morals of our city's youth!"

When we arrived in front of the store window, a group of youngsters I had hired especially for this performance at fifty cents apiece, stood pointing at the picture, uttering expressions of unholy glee and making grimaces too sophisticated for their years. Comstock swallowed the scene and almost choked. "Remove that picture!" he fumed, and when the shopkeeper refused, the Anti-Vice Society appealed to the courts. This brought the picture into the newspapers and into fame. Overnight, the lithograph that had been rejected as a brewer's calendar, became a vital national issue. Songs were written about it, actors wisecracked about it, reformers denounced it, and seven million men and women bought copies of it at a dollar apiece, framed it and hung it on the walls of their homes. The name of the picture was "September Morn." There was no more immorality or suggestiveness to it than sister's photograph as a baby in the family album.

Reichenbach's version of events makes a great anecdote, but there are some problems with it. First of all, placing him at the scene is problematic. He claims that he had "applied for work at a small art shop," but it is odd that he would have needed to seek work at an art store in 1913 since, at that time, he was already working full-time as a press agent. We know this because the August 24, 1913 issue of the

Washington Post contains a brief item about some of his publicity work during that period:

Three press agents have been employed to exploit the three-star combination -- Gertrude Hoffmann, Mlle. Polaire, and Lady Constance Richardson. They are Abraham Levy, Harry Reichenbach, and Nate B. Spingold...

Reichenbach will represent Mlle. Polaire. This selection is thought to be particularly fitting and harmonious, because Polaire is conceded to be the ugliest woman in the world, and Reichenbach never has been mistaken for Adonis. Also he is a globe-trotter, who once on salary decorated windows in South American cities in a state of catalepsy as exhibit A for a traveling hypnotist.

But there's a larger problem with Reichenbach's account. He got the city wrong. The "September Morn" controversy started in Chicago, not New York.

The Chicago Controversy

The American "September Morn" controversy started in early March 1913 when a police detective noticed a copy of the painting hanging in the window of Fred Jackson's art store located at 44 Wabash Avenue in Chicago. The officer, believing the picture to be indecent, ordered Jackson to remove the painting from the window. Initially Jackson complied, but soon returned the painting to the window.

Seeing this, the detective notified his superior officer, Sergeant Jeremiah O'Connor, who then went down to the art store, bought a copy of the painting and took it to show to the mayor. The Sergeant and the Mayor both agreed the painting was indecent and was in violation of the municipal code which banned the exhibit of "any lewd picture or other thing whatever of an immoral or scandalous nature." They decided to prosecute Jackson, believing that the case would be a useful test of whether nudity in art violated the city ordinance.

The police action outraged Chicago's artistic community. Mr. Jackson responded by removing the painting from the window of his store, but replacing it with two statues of the Venus de Milo. One he kept nude. The other he dressed in clothes.

The case was heard on March 20, 1913. Twelve jurors were first instructed to examine the painting. Then the testimony of "experts" was heard. Mrs. Elin Flagg Young, superintendent of schools, testified that she thought the nude in art should not be seen by children younger than fourteen. Father O'Callaghan testified that the picture was immoral because "it stimulates lust. It is an improper exhibition of human nakedness."

Despite this testimony, the jury acquitted Jackson after deliberating for only thirty minutes. Jackson celebrated his victory by giving each of the jurors a copy of the picture, which they all accepted with thanks.

Jackson's victory inspired a mood of celebration in the city. Numerous shopkeepers placed copies of "September Morn" and other artistic nudes in their windows. Irritated by this, the city council amended the ordinance the next month in order to specifically prohibit "nude pictures in any window, except at art or educational exhibitions." This only further inflamed the public's interest in the controversial painting, whose fame had, by then, spread from coast to coast.

The Chicago court case slowly made its way through the appeals process, and a year later, in May 1914, the First District Appellate Court delivered its opinion: “the picture is not indecent, although that may not be said of much of the exploiting to which it has been subjected.” That was the final legal word on the matter.

The New York Controversy

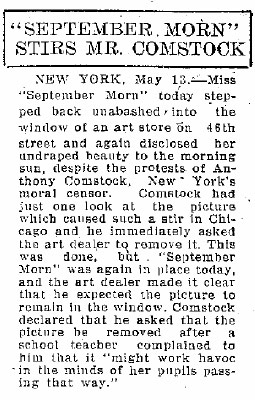

Clipping from

The La Crosse Tribune, May 13, 1913

On May 9, 1913, two months after the first trial in Chicago, Anthony Comstock was walking down West Forty-Sixth Street. When he came to the storefront of Braun & Company art dealers he stopped in shock. There, displayed in the window, was a copy of the now notorious "September Morn."

Comstock had apparently been tipped off about the painting's presence. Newspaper accounts quote him as saying that a school teacher had telephoned him to complain that the painting, visible from the street, was corrupting the morals of her pupils who could see it as they passed by.

Comstock stormed into the store and ordered the painting's removal. The May 11 edition of the

New York Times reported the conversation that ensued inside the store:

Mr. Comstock entered the store and addressed James Kelly, a salesman.

"Take her out at once."

Kelly looked his surprise.

"The picture of the girl without any clothes on," Mr. Comstock said.

"But that is the famous 'September morning.'" Kelly explained.

"There's too little morning and too much maid." Mr. Comstock said severely. "Take it out."

Kelly refused, saying he did not know what business it was of the visitor to make the demand. Mr. Comstock threw back the flap of his coat, displayed his badge of office, and identified himself. Kelly then got the picture hook and hauled in the picture...

When Manager Ortiz returned and learned what had taken place he ordered the "September Morning" put back in the window. It was there yesterday.

"I will keep it on display if I have to spend the value of my entire stock in contesting the point with Mr. Comstock," Mr. Ortiz said.

Philippe Ortiz, manager of the store, kept "September Morn" in the window for five more days, constantly expecting Comstock to return and charge him with indecency. However, Comstock never returned. Finally, Ortiz removed the picture simply because it had already been up there a week longer than he had originally planned to display it, and the crowds outside the window, gathered to get a peek at the controversial painting, were preventing his regular customers from entering the store. Ortiz wrote an angry letter about his experience with Comstock to the New York Times:

"It has been hinted to me that Mr. Comstock grasped this opportunity to secure for himself a little publicity. If it be true, he has certainly achieved his aim. I think that the little girl in "September Morning," my firm, and myself have already done him far too much honor by giving his name a chance to be printed in connection with ours."

Reichenbach's Role

It's clear Reichenbach could not have played the role in promoting "September Morn" that he later claimed. His account has him as the main architect of the painting's fame. However, even if he did advise the New York art dealer to display the painting in his store window, the painting at that point was already embroiled in controversy, thanks to the Chicago trial, and nationally famous.

Reichenbach probably never even worked for the art dealer. Contemporary news accounts make no mention of Reichenbach, although they mention the store clerk and manager by name. Moreover, the store manager made no mention of having 2000 copies of the painting to sell, as Reichenbach asserted. In fact, the manager noted that the crowds outside his window hurt his business, because it prevented his regular customers from entering the store.

September Morn in Popular Culture

Thanks to the controversy surrounding it, the September Morn image became an iconic part of American popular culture during the early twentieth century. Some put the sales of the painting at over seven million copies. But since the vast majority of these copies were illegally pirated, Chabas never saw much profit from the painting's popularity, though it did make him famous. He once remarked, "Nobody has been thoughtful enough to send me even a box of cigars."

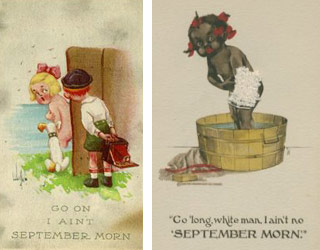

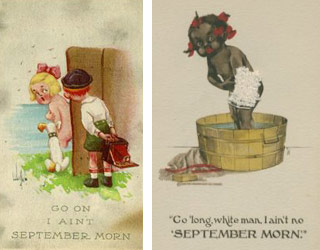

Early twentieth-century parodies of

September MornDespite its enormous sales (or perhaps because of them), art critics later sneered at the painting, classifying it as lowbrow kitsch. However, the controversy surrounding the painting is credited with helping break down American opposition to the display of nudity in art.

September Morn went on to feature in many different ways in popular culture:

Numerous parodies of it were produced (including the two shown to the right).

In 1913 Stanley Murphy penned a popular song: "September Morn (I'd Like to Meet Her)."

In 1913 Florenz Ziegfeld (of Ziegfeld's Follies) presented onstage a recreation of

September Morn starring Ann Pennington, a dancer later known for her dimpled knees. The New York Sun noted that "unfortunately this September Morn wore silk tights which bagged at the knees a bit and wrinkled in the wrong place."

In 1914 a popular musical stage production of September Morn was produced and toured throughout the United States. One newspaper gave this description of the play: "The play, of course, gets its name from the painting of the same name which stirred up comment from coast to coast. The story of the piece has to do with the aspirations of one Rudolph Plastic, owner of an art studio, who claims to have been the painter. Of course, Rudolph does not even know how to paint a picket fence. The model of "September Morn" is laid claim to by an actress who has instructed her press agent to circulate the rumor that she is the original. The ludicrous moments when the two impersonators are dodging each other and when a chesty old army officer who has fallen in love with the actress, discovers that she is a good friend of his wife's, creates enough laughter and plot for six musical plays. The scenery is prettily designed and painted and the costuming introduces the latest Parisian costumes."

In December, 1914 the students of Wooster College in Ohio threw copies of september morn on a bonfire, along with other "erotic literature and questionable pictures of all sorts." The bonfire was the climax of a week long religious revival at the college.

In 1923 the U.S. Army reportedly rejected a recruit who had a tattoo of

September Morn on his biceps on the grounds that it was obscene.

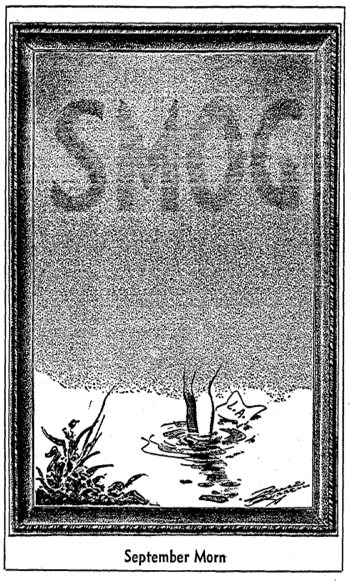

In 1955, the

Los Angeles Times featured

September Morn in an editorial cartoon about the growing smog problem in L.A.

Identity of the Model

Suzanne Delve claimed to have been the model who posed for

September MornPaul Chabas always kept secret the identity of the model who posed for September Morn. However, shortly before his death in 1937, he denied a rumor that his former model was starving and destitute. He stated, "She is now 41, married to a rich French industrialist, and the mother of three lovely children. She is no longer so slender as she was 25 years ago."

A year after he made this statement, an anonymous Hearst press reporter claimed to have found the model. In an article syndicated by King Features, the reporter wrote that the model was a "middle-aged Parisian Matron," childless and divorced, named Suzanne Delve. Delve provided details about posing for Chabas when she was a fifteen-year-old girl, while her mother and Chabas' wife looked on:

Vividly she described the scene. How nervous she was as she disrobed and took up a position on the model's stand in the big room all filled with dancing lights and shadows. How her mother had continued talking to her in an effort to divert her mind and keep her from being overly nervous. How Mme. Chabas, seated at the piano, rendered soothing tunes.

"Instinctively," explained Suzanne Delve, "I took the pose that you have seen immortalized in September Morn, or Le Crepuscule, as it is called on the Continent. "Hold it!" Chabas cried in a quiet but firm voice. And so I remained like that on the model's stand."

Mme. Delve went on to explain that the painting was not made at Lake Annecy as many people still suppose. it was merely filled in and finished there.

However, other women have also been named as the model. According to

some accounts, the body of the

September Morn girl was that of a local peasant, but the head was that of an American, Julie Phillips, whom Chabas sketched while she was sitting in a Paris cafe.

Ownership of September Morn

September Morn was purchased in 1913 by a Russian, M. Leon Mantacheff, who hid it in Moscow during the Russian Revolution. Eventually, it came into the private art collection of Calouste S. Gulbenkian. From there it made its way to a Philadelphia broker, who presented it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1957, where it remains to this day.

Links and References

- "When is art art? When wicked?" Chicago Daily Tribune. March 14, 1913. pg.3.

- "September Morn pits her beauty against censors." Chicago Daily Tribune. March 21, 1913. pg. 1.

- "September Morn Wins Case." Chicago Daily Tribune. March 22, 1913. pg. 3.

- "Comstock Dooms September Morning." The New York Times. May 11, 1913. pg. 1.

- "Wearies of Waiting a Comstock Arrest." The New York Times. May 15, 1913. pg. 7.

- "September Morn given flame bath as college students get 'religion.'" The Washington Post. December 2, 1914. pg.5.

- Harry Reichenbach. Phantom Fame: The Anatomy of Ballyhoo. Simon and Schuster. New York. 1931.

- "Bared at Last -- The Girl Who Was 'September Morn'" The Port Arthur News. January 10, 1937.

- Carson, Gerald. (1961). "They knew what they liked." American Heritage. 12(5).

- September Morn, Sniggle.net.

Comments

And that's the rest of the story 😉