Back in 1960, a story got around about a TV viewer in the South who thought he saw a black man kissing a white woman on a popular TV show. So he wrote to the sponsor of the show to complain. The sponsor acted quickly to calm the man and assure him that they would never sponsor a show on which such an act occurred. They flew an account executive down to see the man and held a private screening for him, to demonstrate to him that the actor in question was actually white. His local station had accidentally broadcast the show at a high contrast ratio, making the actor appear darker than he really was.

, heard about this, he was outraged. To him, it epitomized the corporate urge to be bland and inoffensive so as to never lose a customer, even when offending a racist would have been the morally courageous stance to take.

It's worth noting that it's not clear whether the story of the account executive and the racist viewer is true. Krassner insisted it was, but he never provided a source for the tale, nor any specific details. So it's possible he was reacting to an urban legend. Nevertheless, the story inspired him to take action. He decided a hoax was in order.

His idea was to convince a TV network and its sponsors that they had offended a whole bunch of people, but give them no idea how they had done so. He imagined all the account executives sitting around fretting about what they might have done that was so bad, frantically rescreening their TV shows to pinpoint the source of the offense in order to avert a mass boycott of their sponsors' products.

To pull this off, Krassner first selected what he felt was the most bland and inoffensive show on TV —

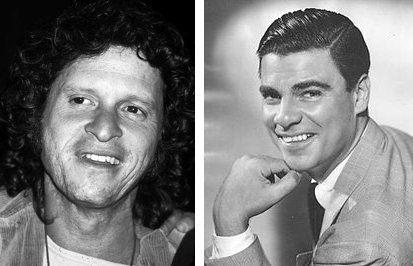

. It was a show hosted by

on which a celebrity came on disguised in a costume, and then a panel of other celebrities had to guess who he or she was.

He then asked his readers to all write in to the show and its sponsors and complain about some imaginary offensive thing that had occurred on one of the shows. Everyone, he instructed, should focus their complaints on the same specific episode airing Friday night, April 1st (1960) on NBC, 9:30 E.S.T. — making it an April Fool's Day prank.

"Use your own wording," Krassner said. "

" The idea was to be indignant but elusive. It was important that the account executives not know what they had done to offend so many people! He referred to it as a "stereophonic hoax" because the complaints would be coming from multiple sources, as if in stereo.

The readers of The Realist eagerly embraced the plan.

Soon after the show aired, John G. Fuller reported in his "Trade Winds" column in the Saturday Review that he had heard that Masquerade Party had received several hundred complaint letters, and that "the sponsors are still screening and rescreening the kinescope to find out just what went wrong."

Krassner provided a more detailed report on the success of the hoax in the June 1960 issue of

. His article, in its entirety, is below.

Case History Of a TV Hoax

Well, boys and girls, as you remember, in our last episode, the Realist was about to crash Masquerade Party with letters from our readers complaining about something "offensive" on their show.

John G. Fuller wrote about the hoax in his column in the

Saturday Review:

"Alarmed at the hypersensitivity of most TV sponsors to often unwarranted public criticism ... [the

Realist] urged ... readers to pick out an innocuous and frequently inane network show on a certain date, and to write the sponsors about some vague and indescribable thing that happened on the show. The letters were to be indignant, but elusive; critical, but undefined."

He reported that more than a hundred

Realist readers wrote in to the show, the sponsors, the ad agencies, etc.

Let us now review four case histories.

Case #1: Bob Calese. He wrote in to co-sponsor Hazel Bishop: "In view of what happened on Masquerade Party Friday night, I can assure you that no woman in my family will ever use any of your products again as long as I live. You know what I mean!"

The next day his wife, Phyllis, got a call from the producer of the show. She said that her husband wrote the letter and that she had no idea what it was that upset him so.

The producer said he'd call back. Bob knew he couldn't possibly carry off the situation without breaking up, so they decided that Phyllis wold take the call and say that he was furious, wouldn't even discuss it with her, didn't want to be bothered by them ever again, and that she'd seen him in these blind rages before and nothing could be done.

Actually, on the night of the show, the Caleses were attending a forum on the subject, "The First Amendment and the U.S. Supreme Court." And even if they had been home, they wouldn't have watched the show. They don't have a TV set.

Case #2: Paul I. Lewis. He

was able to carry off the situation without breaking up. Following is the telephone conversation which ensued between a Masquerade Party distaffer and him.

She: You sent us a letter stating that something on our show offended you. Your letter was vague and we have no idea what it was that you found so offensive; could you please be more specific?

He: What do you want me to say?

She: Well, Mr. Lewis, you wrote the letter so you must know what it was that bothered you.

He: Did you watch the show?

She: Mr. Lewis, I happen to work on the show. I know everything that goes on and I don't know of anything that could have been wrong or offensive on Friday's program.

He: Oh. Well, then if you work on the show, I guess you would know everything that went on. You mean you didn't catch it?

She: Catch what, Mr. Lewis? Will you kindly be more specific. You wrote us the letter and it was very vague. I'm calling you to ask you questions and instead you are asking me questions. Now will you tell me what you found that was salacious on our show. We feel that we put on good clean and wholesome entertainment with Masquerade Party and when we get a letter such as yours we want to discover what was considered offensive.

He: I feel that it was fairly obvious. You must have received many letters commenting on it. Perhaps they have been more specific.

She: No, Mr. Lewis. In fact, yours was the only (sic!) letter we received of this kind.

He: Well, if mine was the only letter, I guess it would appear to be a crackpot complaint, If only one viewer saw fit to write to the show I guess this would make him either wrong or just a nut.

She: Our show is viewed by millions of people, Mr. Lewis, and no one has ever called our show salacious or blue as you did in your letter.

He: Then I guess we can conclude that it was a crackpot letter. Why are you people so concerned with just one letter when you have millions who do not complain about what material is used on the show?

She: Mr. Lewis, please stop asking me questions. I have called to find just what it was that moved you to write this slanderous letter. We are concerned with each of our viewers and we feel that your letter made a strong accusation. We feel that you have a responsibility to your letter.

He: What responsibility is that?

She: The responsibility for standing behind what you wrote?

He: Oh, I'll stand by everything I write. What was it you considered slanderous?

She: You said our show was salacious, used blue material that was unfit to be brought into the homes of the viewers. You called our show lewd and dirty.

He: I did not use that last phrase in my letter.

She: You said salacious, Mr. Lewis, and that is what it means. You should look the meaning of the word up before you sit down to write a letter of this kind. Do you often sit down and write letters of this kind?

He: I do know the meaning of the word — and, no, I do not write letters of this kind.

She: then why did you write one this time?

He: I explained that in my letter.

She: Mr. Lewis, you are still being vague. Just what was it that bothered you?

He: The incident on the show.

She: What incident?

He: Perhaps you missed it.

She: I missed nothing. I know everything and every word that was used on the show. I explained to you that I work on the show and I watch the show and I know everything about the show. Now will you please just tell me what it was that prompted you to say we used blue material on our show?

He: Since I'm the only one who wrote a letter, maybe I misinterpreted what I saw. A few friends of mind commented on the incident and I decided to write my opinion on the matter.

She: Did your friends find the same fault with the show?

He: Yes.

She: I found nothing wrong on the show, Mr. Lewis, yet you and your friends did. Would you please tell me exactly what it was that bothered them and you.

He: You want me to say it over the phone?

She: Why not? It was on the show. Millions of people saw it and no one seemed offended ... There was certainly nothing said that could be considered salacious or blue or immoral.

He: That would be a matter of opinion. It would depend on the viewer's moral values as to how he would interpret what he saw and heard.

She: I understand that, Mr. Lewis. But I would like to know how you interpreted what you saw and heard.

He: My letter covered that.

She: Mr. Lewis, are you going to tell me the exact words that you found offensive?

He: I think it would be wise not to.

She: All right, Mr. Lewis. We do not consider our Masquerade Party a salacious or immoral show. The next time you decide to write us a letter of this kind, please be more specific or do not bother to write at all. (Click!)

He: 'Bye.

Mr. Lewis (who, incidentally, once won a free trip to Cuba and turned it down because he disapproved of the Batista regime) received a call the next week from an Allstate Insurance agent. Having read in an article by Al Morgan in

Playboy that Allstate wouldn't allow a suicide to take place on

Playhouse 90, he told the agent that he wouldn't even consider buying insurance from Allstate until there was a suicide on a

Playhouse 90 production sponsored by them. The agent said he would take it up with his superiors.

Case #3: Steve Farr. He wrote to co-sponsor Block Drug Company, promising to stop using Poli-Grip. Actually, he has his own teeth. But he doesn't have a telephone, and so instead of a call, he received this letter from the manager of NBC's Department of Information:

"Dear Mr. Farr:

"This is to acknowledge your critical appraisal of a recent Masquerade Party program.

"It is a matter of genuine concern to us that you found this program objectionable.

"We will most certainly note your sensitive expression of criticism and relay it to the Manager of our Continuity Acceptance Department.

"Thank you for the interest which prompted you to write."

A month later, Mr. Farr was standing in City Hall Park, protesting a hoax by the government on

him—the Civil Defense Drill.

Case #4: A young subscriber from Merion, Pa. — identity withheld on request. He wrote a letter to "The Green Mint, Nytol People" with a ball-point pen. Note that right smack in the middle, there is a sentence fragment — a complete non sequitur — just for the hell of it.

"Dear Gentlemen:

"I am a teenager and my parents have tried to raise me as a decent, god-fearing person and have tried to keep me and my mind pure. We often

used to watch Maskkeraid Party and we thought it was a dandy show. But once in a while those people got on their big-city high horse and said some pretty bad things. Of course my parents were upset and turned the sound off so I wouldn't be perverted. I blushed too. But we still thought the show was tops and right good.

"Gramps and Nana used to like the show alright too. And they were much riled when they heard those things too but jiminy crickets they still liked to watch it until last night. Well, last night you went a might too far. My parents just told me to go straight upstairs and they were just going to switch off the show completely. They did this mainly because I asked them too because they're pretty broad-minded on such matters. I was never so embarrassed in my life. I have heard some pretty filthy low-down tacky things but nothing like last night.

"I always used to wash by mouth out with Green Mint because I think Dick Clark is a pretty swell fellow and a really cool guy and he said he liked Green Mint and wanted me to use it too. I did. It can therefore be seen that whenever a country adopted repressive measures. I aint no egghead intellectual but once in a while I stay up real late studying for a subject in a test in school and I couldn't go to sleep so I used Nytol because everybody said I should because it was good for me. But never again. Do you hear, NEVER AGAIN. I'm not going to help support the corrupting of minds that might be corrupted and don't know what's going on like me. I had it last night. Maskkeraid Party shouldn't be allowed on the air.

"Sincerely yours ...

"P.S. I just poured all the Green Mint in the toilet and flushed it away. NEVER AGAIN!!! I am going to tell everyone I know never to use your products again. Just who do you think you are?"

The producer called up, long distance!

"I was out," the young subscriber wrote to us, "but my mother seemed to suffice ... Although I made it clear in the very first line of the letter that I was not an adult, the sponsors had failed to made this clear when they communicated their distress to the producer (on the first call, unlike second, he did not have a copy of the letter in front of him). Therefore, the first few minutes of the conversation were taken up in establishing that I was not my mother's husband but only a teenager.

"The producer then went on to say that the sponsors didn't understand my letter — what was I so upset about? — and that I was the only person who complained. Mother replied that I rarely watched television at all and that she didn't know anything about it. She further told him that I didn't use Green Mint or Nytol; and she told me that on hearing that piece of information, the producer seemed to lose a great deal of interest.

"He called up again the next morning and asked my mother what my reaction was to the news of the first phone call. She told him that I had laughed. He made sure again that I was just a teenager and did not buy either of the products. he then read her the letter. She was embarrassed. 'No, no, no, my son doesn't speak that way at hom. Why, he's a National Merit Finalist. ... '"

* * *

It was precisely because Masquerade Party is the epitome of

inoffensiveness that we chose it for our hoax.

Take, for instance, the show's emcee, Bert Parks. We'd be willing to bet 20 to 1 that he smiles even while defecating. Apparently, though, this is exactly what the mass audience wants. As a matter of fact, Henry Morgan mentions in next months' "Impolite Interview" that

I've Got a Secret gets letters asking them to fire him because he doesn't smile

enough.

Understand, then, that the name Bert Park is used here as a generic term for an occupational disease. You can easily substitute Ralph Edwards, Kathryn Murray, Jack Bailey, Arlene Francis, Bud Collyer, Loretta Young, Ed Sullivan — yes, that's right, Ed Sullivan: on his St. Patrick's Day show,he bowed to Catholic pressure and deleted a Sean O'Casey segment.

The point being that there is more than one way of smiling into a TV camera.

Playwright O'Casey, you see, is a living symbol of irreverence. In an essay on "The Power of Laughter," he once wrote:

"Laughter tends to mock the pompous and the pretentious; all man's boastful gadding about, all his pretty pomps, his hoary customs, his wornout creeds, changing the glitter of them into the dullest hue of lead. The bigger the subject, the sharper the laugh.

"No one can escape it: not the grave judge in his robe and threatening wig; the parson and his saw; the general full of his sword and his medals; the palled prelate, tripping about, a blessing in one hand, a curse in the other; the politician carrying his magic wand of Wendy windy words; they all fear laughter, for the quiet laugh or the loud one upends them, strips them of pretense, and leaves them naked to enemy and friend.

"Laughter is allowed when it laughs at the foibles of ordinary men, but frowned on and thought unseemly when it makes fun of superstitions, creeds, customs, and the blown-up importance of brief authority. ..."

And so, televised 'humor' is for the most part limited to situation comedies — which are in reality nothing but castrated sermons with a laugh track — and the panel shows.

Betsy Palmer, who has risen in the panel show hierarchy from

Masquerade Party to

I've Got a Secret, crystallizes the philosophy of that institution thusly:

"The thing on a panel show is, you have to seem as if you're having fun. That's what it's all about, you know. The guessing bit doesn't matter al all."

The prevailing theory in the television industry is that every letter received represents 50,000 that

weren't sent — and commercial backers of a medium certainly don't want to alienate their market. The

Realist's hoax in effect satirized the frightened state of mind that propagates this theory.

Accordingly, we'd like to sugest now a few constructive 'hoaxes' in which

Realist readers may want to participate.

1.

CBS Views the Press was a courageous radio program which was pressured off the air. Jack Paar has eulogized it. Paar, however, criticizes the press only when

he is involved, directly or indirectly. Let's call his bluff and request that a qualified journalist appear once a week on his show with a special "Tonight Views the Press" feature.

2. If you have seen Joyce Brothers' show, you have probably been aware that it is devoted to the dissemination of pseudo-liberal advice in a most unspontaneous format. Dr. Albert Ellis is a willing would-be antidote to her conventionality. Channel 13 (NTA) is the most likely late-night spot for him. If you have felt rapport with Dr. Ellis' rationality (issues #16 and #17) — and if NTA is seen in your area — write.

3. There are those afternoon children's programs which exploit family relationships in their commercials ("And be sure to ask your Mommy

nicely"). Letters with

specific grievances about this might have more effect than you think.

We discussed this with syndicated political cartoonist John Fischetti. He has two sons, age 8 and 10. A few years ago, they pestered their mother for Pie-O-My pudding cake, and she finally gave in and bought it — and it was absolutely awful; no one in the Fischetti household could eat it. On another occasion, there was a very dramatic and misleading film of an animated space station. The kids thought they were going to get something like it; instead, it turned out to be a piddling plastic toy.

Twice sold — twice burned.

The kids are now quite disillusioned with advertising, and when an announcer makes his claims, they'll say, "That's a lot of baloney." To what extent this alienation of the

future market is typical, is purely speculative.

But the implications are indescribably delicious.