In their 1895 work

Photography: Artistic and Scientific, authors Robert Johnson and Arthur Brunel Chatwood offered a defense of retouching portraits (a practice sometimes maligned even back then). They also showed an example of what was possible. They wrote: "In condemning retouching which is only senseless stippling for the direct purpose of making all faces alike, of bringing them all to one standard of smoothness and roundness, we most heartily join. But that judicious retouching is a very great advantage we have no doubt whatever; it is an absolute necessity, in our opinion, in order to obtain the best result, which is admittedly the object of all art.

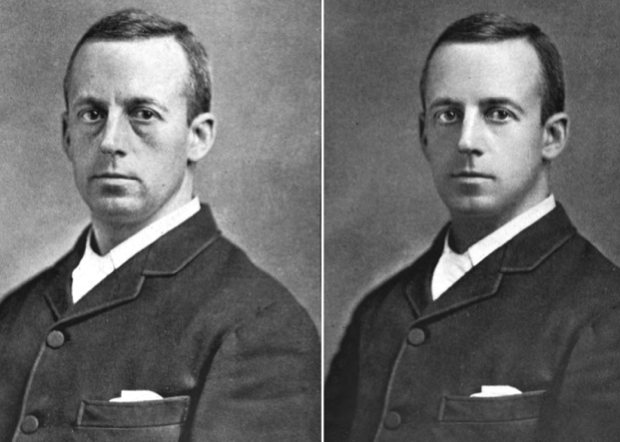

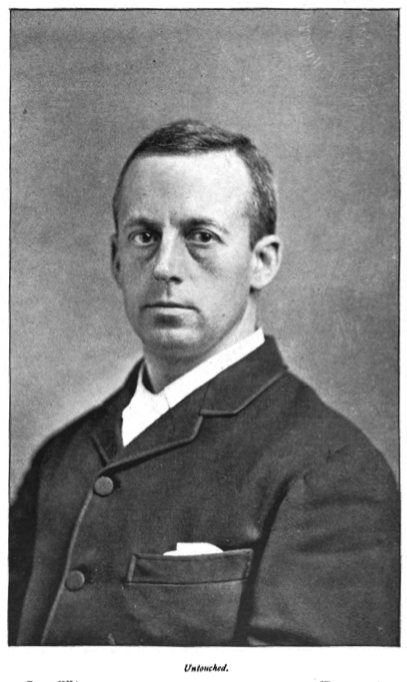

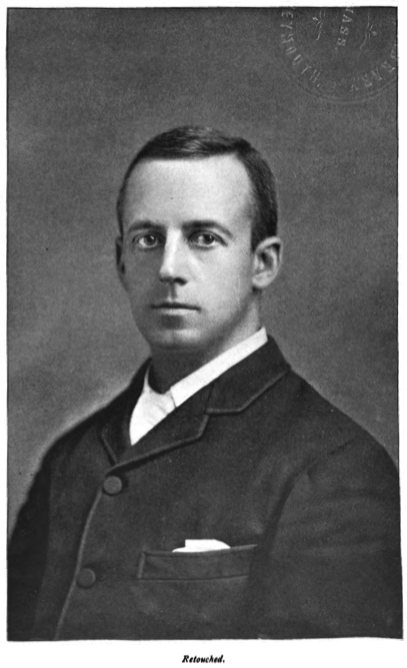

In the accompanying illustration... three different stages of one negative are presented to the reader. The first is a rough proof, nothing in the way of retouching having been done to the negative;

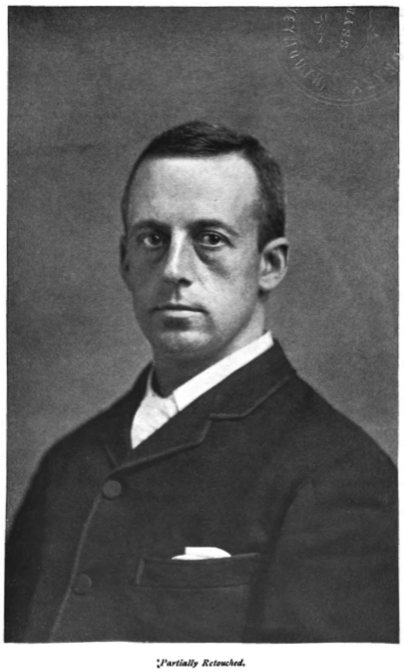

the second is after the knife has been used, and the attention may be drawn to the alterations made, a small patch of light taken from the hair on the outline above the ear, a small patch from the ear itself, the light on the neck caused by the flesh being forced up by the turning of the head (this light on the rough proof is below the outer edge of the jaw); the point of the nose is very slightly scraped, and where the light has caught the muscles round the mouth it has been reduced; the depression between the eyebrows has been altered by scraping the light from one side, and a touch has been taken from the necktie, that is the extent of the scraping.

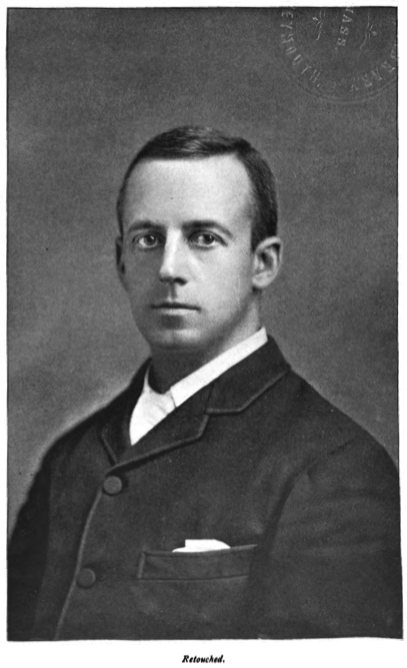

The third illustration shows the retouched picture. It should be mentioned that this negative has been retouched far more than is, as a rule, necessary. The head was posed and lighted with the distinct purpose of needing a great deal of retouching; it is introduced here to show how much can be done without materially altering the shape of a feature or destroying the likeness. If it be closely examine it will be seen that the greatest piece of work has been the addition of light under the eyes. We have omitted to mention another item of scraping, the light on the shaded side of the neck has been reduced; this was a reflected light.

In ordinary portraits of ladies this amount of retouching is expected. In cases of ladies who have been noted for beauty, but whose beauty has somewhat faded, this would be considered a small amount of retouching. One might think that eminent men, whose faces are well known to thousands, would object to so untruthful portrait of themselves going before the public; but it is not so. There seems to be no class, no age, no station in life, no amount of intellectual attainment even, that can divest a man's mind of the idea that he looks younger than he really does; perhaps this is a wise provision of nature, which wilfully blinds us to our own physical, as well as mental, imperfections. Anyhow, the fact remains that scientists, politicans, divines, writers, artists, all are alike in this respect.

Links and References

- Johnson, R. and Chatwood, A.B. (1895). Photography: Artistic and Scientific. Downey and Co. London. pgs: 133-134