The Cradle of the Deep, published in 1929 by Simon and Schuster, was advertised to be the genuine autobiography of Joan Lowell, in which she told the story of her childhood aboard her father's schooner, the

Minnie A. Caine.

According to Lowell, her father, Capt. Nicholas Wagner, took her onto his windjammer when she was only eleven months old, and she lived there almost continuously until she was seventeen. She claimed her father was engaged in the copra trade between the South Sea Islands and Australia, and that she was the only "woman thing" on the schooner — a girl among rough men. She claimed that she didn't see another woman for years at a time, and that she learned about female biology by cutting up a mother shark.

Lowell's memoir recounted the various adventures she experienced during this unconventional childhood: how she learned to "spit a curve in the wind;" how she once single-handedly harpooned a whale; how she learned to cuss for four minutes without repeating herself; how she played strip poker with the crew and "lost her pants"; how she lived through a water spout (which her father busted up by firing a rifle at it); and how she saw men killed by a falling boom and washed overboard.

Lowell's adventures ended, according to her, when the schooner was destroyed by fire and sank three miles off the coast of Australia. She survived by swimming to shore, with three kittens clinging to her back.

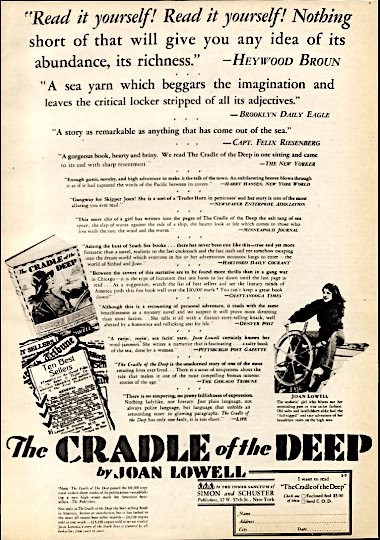

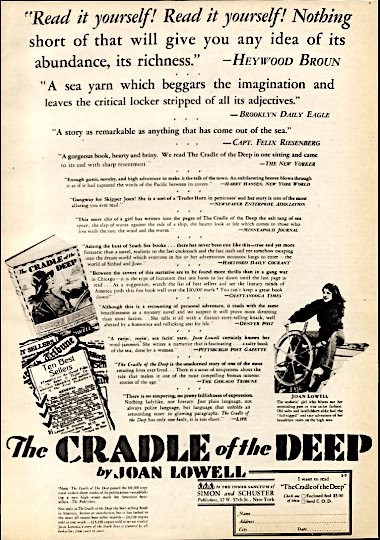

1929 print ad for

The Cradle of the Deep

The memoir was well received by critics and had strong sales, earning Lowell over $50,000 in royalties. The Book-of-the-Month Club chose it as their March 1929 selection. D.W. Griffith bought the film rights for $75,000.

However, doubts about the authenticity of the narrative quickly arose. Lowell's adventures seemed too farfetched, and her depiction of life at sea like something out of a Hollywood movie.

Joan Lowell in 1923

These doubts were confirmed a few weeks after the publication of the book, when reporters for the

San Francisco Chronicle and

Berkeley Gazette investigated Lowell's past and discovered that almost none of it was as she had claimed.

In reality, Lowell had spent very little time at sea during her childhood. She grew up in Berkeley, California as Helen Joan Wagner, where she attended the Garfield School. Classmates remembered her acting in many school plays. After graduating in 1920, she enrolled at a San Francisco business college, and a year later took a job as a private secretary to a San Francisco lawyer, before landing a role in a movie (a feature about a South Sea Island).

As for the

Minnie A. Caine, it was a real schooner, but it hadn't ever sunk. It once caught fire while at pier in Adelaide harbor, but was repaired and sailed home, and in 1929 it was safely docked in San Francisco harbor. Her father had captained it for only one year. Joan Lowell had only spent a few months on board the schooner with her father, during which time she was accompanied by her mother and two brothers.

Controversy

The revelation that almost none of Lowell's memoir was true was particularly ironic since a number of critics had praised the book for its authenticity. Fanny Butcher, reviewing it for the

Chicago Daily Tribune, had written, "There is veracious salt in the air, a simplicity in the telling of tales that are either funny or gruesome or mixed up both, and a record of reality which make 'The Cradle of the Deep' one of the very best of the new school of adventure-autobiographies."

After the exposure, literary critics Lincoln Colcord and Heywood Broun debated the significance of the hoax in

The Bookman journal. Colcord expressed dismay that the hoax hadn't caused a greater sense of outrage:

I believe that today, for the first time in literary history, we have the spectacle of a hoax of first proportions which has been fully exposed, while no one concerned in the fraud, either innocently or deliberately, seems greatly disturbed.

He worried that this signified a decline in ethics within the publishing industry. Broun responded that Colcord's sense of shock and concern was overblown and misplaced, noting that, "From the days of Marco Polo to Joan Lowell's the public has always granted the returned traveller a license even wider than that allowed to poets."

Lowell herself was dismissive about the scandal and insisted, despite the evidence, that most of the book was true. In an interview with

The Pittsburgh Press she said, "Eighty per cent of it was true and the rest I colored up. I made some changes to protect people and the rest to make it better reading. That's an author's privilege."

In another interview she said, "Any damn fool can be accurate — and dull."

Embarrassed by the scandal, the Book-of-the-Month Club offered its readers a refund. However, no action was taken against Lowell herself. The main negative consequence of the scandal for her was that the reputation of being a literary hoaxer clung to her for the rest of her life.

Parody

The Cradle of the Deep inspired humorist Corey Ford to write a parody of it, which he titled

Salt Water Taffy. It was published in June 1929. The

Oakland Tribune offered the following description of its plot:

In this book it is June Triplett who was not more than three hours old when she first reported aboard the schooner of her father, Captain Ezra Triplett. Pictures in the work, and there are many, show Ezra to resemble Heywood Broun.

At seven June cut open a female shark and found a copy of 'What Every Girl Should Know' inside. She was the first white woman who witness the Dance of the Virgins — and even learned how to become one.

Lowell's Later Life

In the early 1930s, Lowell worked briefly as a journalist. This experience served as the basis for her second book,

Gal Reporter.

In 1932, she announced that she and her father were departing on a four-year voyage around the world in a schooner, the

Black Hawk. However, they didn't make it any further than Guatemala. Footage from the trip became the basis for

Adventure Girl, a movie released in 1934 by Van Beuren/RKO. The movie was widely panned.

In 1936, she married a ship captain, Lee Bowen, and moved with him to Brazil where they started a coffee plantation. She wrote a memoir about her life in Brazil, titled

Promised Land, which was published in 1952.

In 1957, she was briefly jailed for writing bad checks. She claimed that she had to because she was "under threats from an organized gang."

She died in 1967 in Brazil.

Links and References

- "Attack truth of girl's thrilling tale of the sea," (Apr 6, 1929), Chicago Daily Tribune: 10.

- Butcher, F. (Mar 9, 1929). "Sea's Girl Child Tells Story of Windjammer," Chicago Daily Tribune: 13.

- Chesnut, A. (Mar 17, 1930). "Joan Lowell, ex-sailor, running farm in Pennsylvania," The Pittsburgh Press: 22.

- "Chums of 'Skipper Joan' doubt story," (Apr 6, 1929), Berkeley Daily Gazette.

- Colby, A. (Mar 14, 2008). "Meet the grandmother of memoir fabricators," Los Angeles Times.

- Colcord, L. & Broun, H. (June 1929). "Are Literary Hoaxes Harmful? A Debate," The Bookman, 69: 347.

- "Writer spends pleasant time in Latin jail," (July 11, 1957), Panama City News: 9.

Comments