Media organizations competed to buy the rights to Hitler's diaries, which turned out to be one of the most outrageous fakes in the history of journalism.

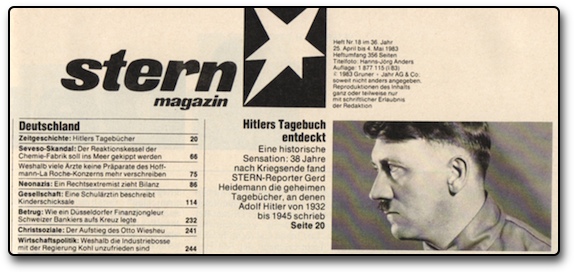

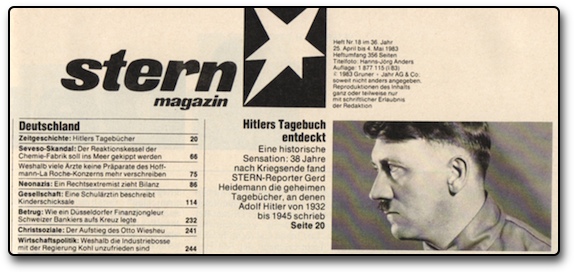

On April 22, 1983 the glossy German news magazine

Stern issued a press release announcing what it promised was "the most important historical event of the last ten years." It had discovered the personal diary of Adolf Hitler -- a massive, multi-volume work spanning the years 1932-1945.

Stern's announcement generated a media frenzy. Magazines and news agencies bid for the right to serialize the diary. Journalists, historians, and World War II buffs eagerly anticipated what revelations it would contain. Skeptics, however, insisted it had to be a fake.

The skeptics turned out to be right. Less than two weeks after

Stern's initial announcement, forensics experts at the West German Bundesarchiv issued a press release of their own, denouncing the diaries as a "crude forgery."

The debunking of the diaries proved just as sensational as their discovery. Careers were ruined, and people went to jail. When all the dust settled, the diaries turned out to be one of the most expensive fakes in history. By some accounts, the entire debacle cost

Stern as much as 19 million marks.

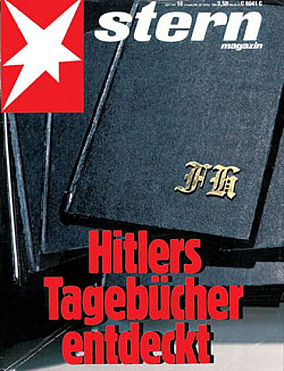

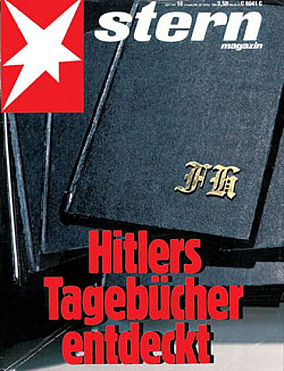

Front cover of Stern's special issue,

announcing the discovery of Hitler's diaries.

The Beginning: Gerd Heidemann and His Boat

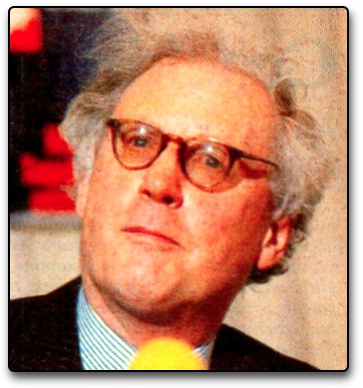

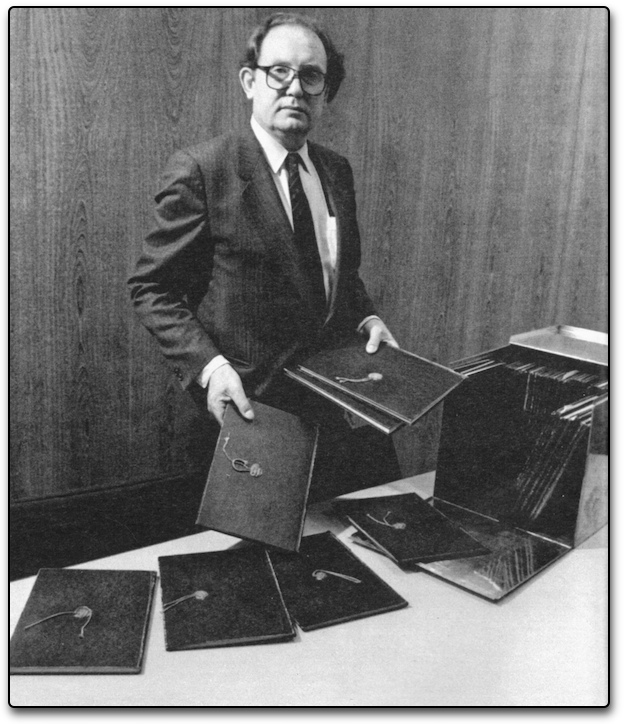

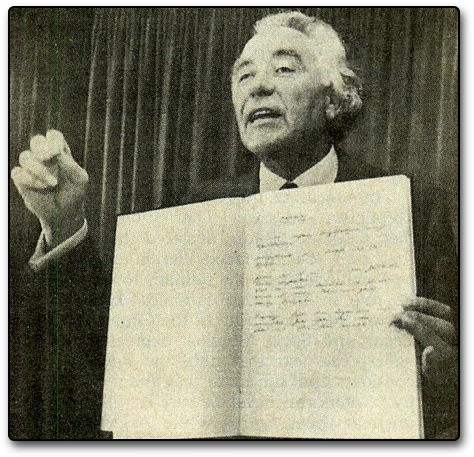

Gerd Heidemann, a reporter for

Stern, stood at the center of the hoax. He was both its primary instigator and, paradoxically, one of its main dupes.

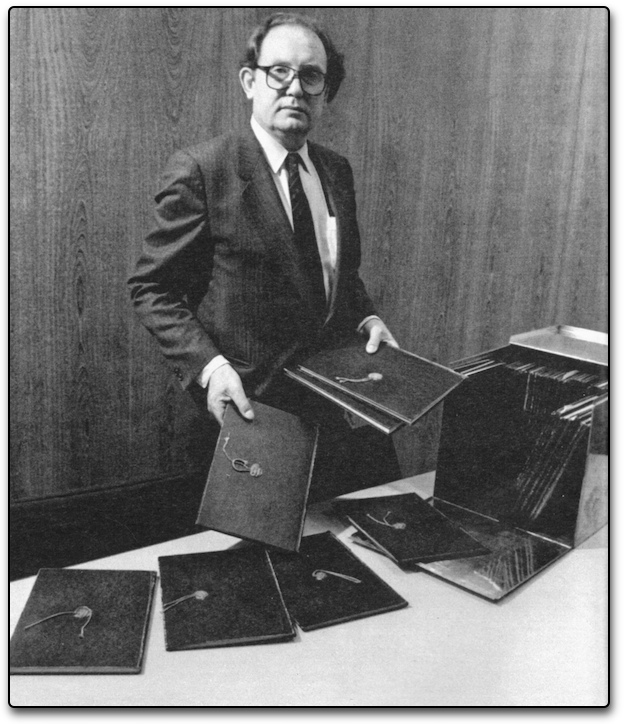

Heidemann poses with the diaries. Image from Stern magazine - Apr 22, 1983.

Heidemann had been a full-time reporter for

Stern since 1955. He was known by his colleagues for being an enthusiastic, though overly gullible, researcher. He was also an avid collector of Nazi memorabilia. The crown jewel of his collection was a boat, the

Carin II, originally owned by the Luftwaffe commander Hermann Goering. Heidemann bought the boat in 1973, planning to fix it up and resell it for a profit, but the repairs proved far more costly and time-consuming than he had anticipated. After seven years he was deeply in debt and needed to sell the boat. It was while trying to find a buyer that he stumbled upon the existence of the Hitler diary.

In January, 1980 Heidemann visited the Stuttgart home of Fritz Steifel, a wealthy collector of Nazi memorabilia, hoping to persuade him to buy the

Carin II. Steifel wasn't interested, but while Heidemann was there, Steifel showed him an unusual and very rare item he had recently acquired. It was a single, black-bound volume of Hitler's diary, covering the period from January to June, 1935.

Heidemann was immediately intrigued. He hadn't been aware that Hitler had kept a diary. This was not surprising, Steifel assured him, since almost no one knew of its existence. Steifel then proceeded to explain where the diary had come from, and why its existence had remained unknown for so long.

It had supposedly been rescued from a plane crash in East Germany at the end of the war. It had subsequently come into the possession of a high-ranking East German military official who, in return for hard currency, had smuggled it over the border to his brother, an antiques dealer in Stuttgart. At least, this is what Steifel had been told by the antiques dealer who sold him the volume. Steifel confided in Heidemann that there were apparently twenty-six other volumes of the diary, each covering a six-month period.

Heidemann was hooked. As a journalist, he knew that the discovery of Hitler's secret diary would be the scoop of the century. He pressed Steifel for further details -- Who was this collector that had sold him the diary? How could he be contacted? -- but Steifel clammed up. (Steifel believed the diary was authentic and didn't want to put the dealer in jeopardy by revealing his identity.)

Undeterred, Heidemann rushed back to

Stern to tell his colleagues about his discovery. Most of them greeted his news with indifference, dismissing it as nonsense. His editor specifically told him not to pursue the story. Only one member of

Stern's staff was interested -- Thomas Walde, head of

Stern's historical research division. Together they decided to lure the mysterious antiques dealer out of hiding with an offer he couldn't refuse.

Using his contacts in the murky subculture of Nazi memorabilia, Heidemann learned that the antiques dealer was a man named "Herr Fischer." He arranged to have a message relayed to him.

Stern, the message said, would pay two million marks in return for the complete set of the Hitler Diaries. The message also guaranteed complete anonymity.

The Backstory

The story that Steifel told Heidemann about where the diaries had come from was a central element in the hoax -- and, as it turned out, some details of the story were true. This provided a veneer of historical credibility, and is important for understanding why so many people would believe the diaries were authentic.

During the last days of the war, the Nazis

had attempted to keep valuable documents from falling into the hands of the occupying forces by removing boxes full of official archives from the Berlin bunker and flying them down to southern Germany. They called this removal project "Operation Seraglio." One of the transport planes crashed in East Germany, near the Czech border. Hans Baur, Hitler's personal pilot who was present in the bunker, later recalled that when Hitler heard of this crash he became visibly upset and exclaimed, "In that plane were all my private archives, that I had intended as a testament to posterity. It is a catastrophe." Days later the third reich dissolved and Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide.

It was plausible that the loss of a personal diary -- even though Hitler had never been known to keep one -- could have provoked such a reaction from Hitler.

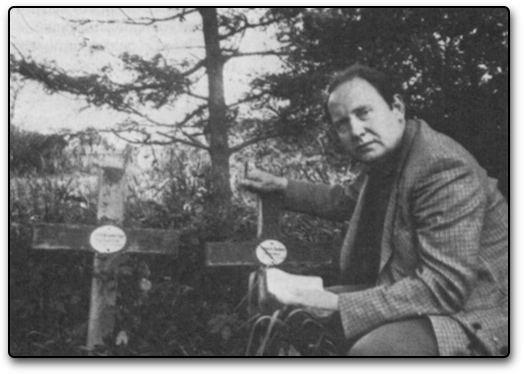

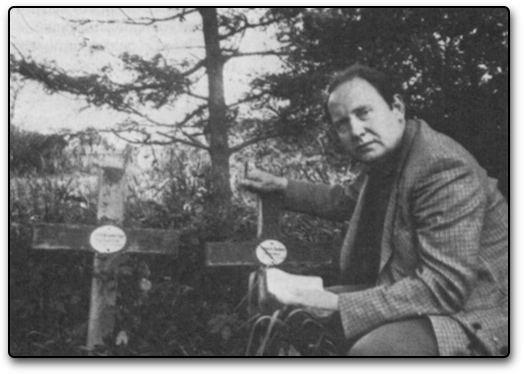

Gerd Heidemann in East Germany, posing beside the graves of the victims of the plane crash from which the diary was supposedly recovered. November, 1980.

Before attempting to contact "Herr Fischer," Walde and Heidemann traveled to East Germany, to try to locate the crashed plane. They succeeded in doing so, and in their minds, this confirmed the entire story about the source of the diary. They could imagine that local villagers must indeed have rescued it from the plane, and that it then came into the possession of an East German military official.

In actuality, there was no evidence that any documents, let alone Hitler's Diary, had survived the crash. The forger had simply stumbled upon Baur's account of the plane crash (Baur had been telling it to whomever would listen for years), and he had then built a fantasy of Hitler's lost diary around the reality of the crashed plane.

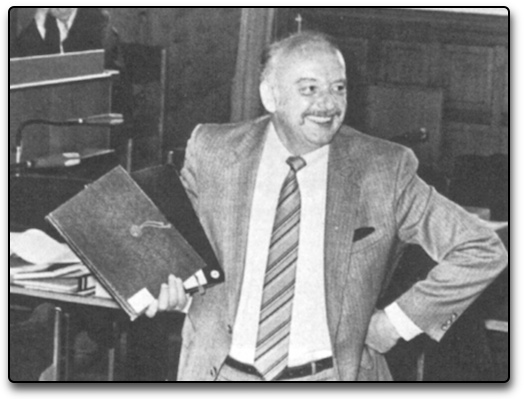

The Forger: Konrad Kujau

Herr Fischer, the Stuttgart antiques dealer, was the pseudonym of Konrad Kujau, a small-time forger. Kujau had dabbled in petty crime before discovering his talent as a forger. During the late 1970s he began making a good living by selling fake Nazi memorabilia to wealthy and gullible collectors such as Steifel. His favorite trick was to add phony "official" certificates of authenticity to fake material. The collectors he sold to rarely asked many questions since they feared attracting the attention of the authorities. Collecting and displaying Nazi memorabilia was illegal in Germany.

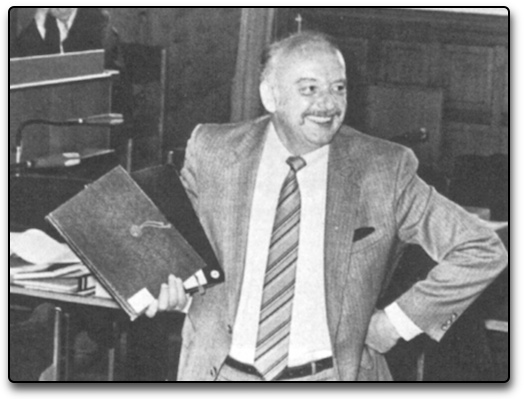

Konrad Kujau

Kujau created the first volume of the Hitler diary almost as an afterthought. He had bought some old school notebooks, intending to use them to catalog his collection. Instead, he hit upon the idea of using one to create a Hitler diary. Steifel immediately bought it.

For Kujau, that might have been the end of the matter. Instead, two years later, he received the extraordinary communication from Heidemann offering two million marks for the complete set of the diaries. Kujau was astounded. That was far more money than he had ever received for any of his forgeries.

Kujau promptly replied to Heidemann that he was willing to do business, but he had a few conditions. First, he stressed the need for absolute secrecy, explaining that his supplier was his brother, who was a general in the East Germany army. If word got back to East Germany of his brother's involvement in such a scheme, it could cost his brother his life. (Part of what Kujau told Heidemann was true. He actually did have a brother in East Germany. However, his brother was a railway porter, not a general.)

Since Kujau hadn't created the diaries yet, he also needed to buy time. So he told Heidemann that the diaries would need to be smuggled out of East Germany one by one -- a process that could take months.

Finally, Kujau insisted that he would deal only with Heidemann himself -- no one else. Heidemann readily agreed to all of these conditions.

Stern Takes the Bait

When Walde and Heidemann made the offer of two million marks, they didn't actually have the money to back that up. Nor did they have approval from

Stern. They were counting on gaining that approval once they knew they could acquire the diaries.

Heidemann and Walde decided to circumvent

Stern's editorial staff and went directly to the managers of

Stern's parent corporation, Gruner and Jahr, with their discovery. The management team, led by Manfred Fischer, was intrigued. They realized that selling the syndication rights to something like Hitler's diary could earn the company a fortune. So, taking Heidemann and Walde at their word that the diary was real, they agreed to pay 85,000 marks for each volume.

Stern's editorial staff, who certainly might have been more skeptical of the diary's authenticity, never learned of this decision until months later. By that time Gruner and Jahr had already spent hundreds of thousands of marks. When

Stern's editors did finally learn what was going on, they assumed that, since so much money had already been spent, the diaries MUST be real.

Delivering the Diaries

Over the course of the next two years, a routine was established wherein Heidemann would transport suitcases full of

Stern's money to Kujau. In return Kujau would present Heidemann with a few more diary volumes.

Heidemann had convinced

Stern to award him a lucrative contract for his role in acquiring the diaries. He was given a large cash advance, promised a royalty of six percent, and thirty-six percent of syndication sales. But the real windfall came from what Heidemann was skimming off the top. What he gave Kujau was a fraction of what

Stern was paying. He squeezed even more money out of

Stern by telling them that the cost of each volume had increased, from 85,000 marks to over 200,000 marks.

Stern obligingly forked over more money.

Meanwhile, Kujau, seeing the cash come rolling in, told Heidemann that more volumes of the diary had been discovered -- over sixty in total.

Stern committed to buying all of them.

Heidemann, flush with cash, went on spending sprees. He bought first-class cruises, new cars, apartments, and large amounts of Nazi memorabilia (most of it fake). At one point he even inquired about the possibility of buying Hitler's childhood home. His spending attracted the suspicion of some at

Stern, but upper management dismissed any concerns about his integrity. In their eyes, he was their star reporter.

Creating The Diaries

Kujau could create the diaries with surprising speed. The most time-consuming part was the initial research to create the content, which mostly consisted of an unimaginative listing of official engagements and party announcements. To obtain this information, Kujau relied heavily on a book by the historian Max Domarus,

Hitler's Speeches and Proclamations, 1932-45.

The sheer tedium of the diary's content ironically made it more credible in the minds of many people. They figured it was so boring, it had to be real. For instance, Henri Nannen, founder of

Stern, said, "I couldn't believe that anyone would have gone to the trouble of forging something so banal."

At the end of each month's entries, Kujau included a "personal" section, for which he invented more speculative material. He had Hitler worrying about his health, or expressing his affection for Eva Braun. Occasionally he had Hitler comment on current events. For instance, he had Hitler write that the "measures against the Jews were too strong for me." The overall effect was to portray Hitler as a far kinder, gentler person than history remembers -- one who was not responsible for the worst atrocities of the Nazi regime. In fact, Kujau's version of Hitler was not even aware of the Jewish holocaust. Some examples of typical diary entries include:

"Opening of the Party Congress. Proclamation. Handing over of Reich insignia to the mayor of the town of Nuremberg. A cultural meeting."

"Meet all the leaders of the Storm Troopers in Bavaria, give them medals. They pledge lifelong loyalty to the Führer, with tears in eyes. What a splendid body of men!"

"My health is poorly -- the result of too little sleep."

"Must get tickets for the Olympic Games for Eva"

"On Eva's wishes, I am thoroughly examined by my doctors. Because of the new pills I have violent flatulence, and - says Eva - bad breath."

After researching the content, Kujau would write a rough draft in pencil. Then he would write in ink in the notebook itself. This final stage was done quite quickly, often taking Kujau as little as four hours. It helped that each volume was quite brief, rarely consisting of more than 1000 words. Kujau wrote the text in an old Germanic script that few could decipher.

The diaries themselves were bound in black, and about 1.5 centimeters thick. Kujau scuffed them up and stained them with tea to give them an old, battered appearance.

He glued initials on to the front cover of each diary. Kujau thought that the initials, which were in a gothic script, were the letters "AH" for "Adolf Hitler." In fact, they were "FH". Luckily for Kujau, no one noticed this mistake.

The Decision to Publish

Stern's original plan was that, after acquiring all the diaries, it would stretch out their publication over as long a period as possible. It hoped, in this way, to squeeze the maximum amount of money from them. According to this strategy, they would first release a book, titled

Plan 3, based upon one volume of Hitler's diary that dealt with Rudolf Hess. It was the most historically interesting of all the volumes, since in it Kujau portrayed Hitler as being aware of Hess's plan to negotiate a peace deal with the British before Hess flew to Scotland.

However, early in 1983

Stern abandoned this plan for two reasons. First, the editors at

Stern convinced Gruner and Jahr that the plan to release the volumes one at a time didn't make journalistic sense. The most exciting scoop was the discovery of the diaries in their entirety. To maximize publicity they had to lead with this story.

Second, other papers had begun to sniff around.

Stern knew that it couldn't conceal the existence of the diaries much longer. If they didn't go public soon, another paper might steal their scoop from right under their nose.

Therefore, the schedule was accelerated.

Stern decided to unveil the diaries as soon as possible, even though Heidemann protested that there was a great deal of material left for them to acquire. (Kujau had been presenting him with an ever-expanding list of Hitler material he could sell them, including a book Hitler had supposedly written detailing his experiences with women, and an opera by Hitler titled

Wieland the Blacksmith.)

The first step, before going public, was to secure syndication deals.

Stern's lawyers began contacting rival news organizations, disclosing the existence of the diaries to them (after swearing them to secrecy). Interest ran high, especially from

Newsweek and Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation.

Stern anticipated being able to negotiate a record-breaking syndication deal. However, before agreeing to a deal, these organizations insisted on being able to send their own experts to verify the authenticity of the diaries.

Examining the Diaries

By early 1983

Stern had already spent approximately nine million marks to acquire the Hitler diaries, but surprisingly it had subjected them to very little expert analysis to verify their authenticity. Part of the reason for this was its obsession with secrecy.

For instance,

Stern had not allowed any professional historian to examine the diaries. If it had, it almost certainly would have learned they were fake. Eberhard Jaeckel, a professor of modern history at the University of Stuttgart, would have been an obvious person to seek an opinion from. And, as it turned out, Jaeckel had previous experience with Kujau's fakes and could have warned them. But

Stern never consulted him.

Stern had relied primarily on handwriting analysis to verify the diaries. It had given handwriting samples from the diaries to three analysts. Unfortunately, it had unknowingly polluted these tests by giving two of the analysts comparison documents that were actually Kujau fakes. Therefore, the analysts were comparing Kujau against Kujau. A third analyst had compared a page of the diaries against genuine samples of Hitler's handwriting, but had nevertheless declared the diary sample to be genuine, which gives some indication of the non-scientific nature of handwriting analysis.

Stern had also submitted a page from the diaries to the german police for forensic analysis, but by the time it decided to go public, it had not received the results of these tests. (Nor had it told the police what it was they were analyzing, which might have prompted the police to give higher priority to the analysis.)

Soon before the public launch of the diaries, on March 28, the German police did provide

Stern with preliminary results from their forensic analysis. They found serious potential problems with the material, but they also indicated that more tests needed to be conducted. Therefore,

Stern decided to press ahead, hopeful that the subsequent tests would turn out okay.

The Experts Arrive

In April both

Newsweek and Murdoch's News Corp. sent independent experts to examine the diaries, in anticipation of signing a syndication deal. Murdoch sent the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

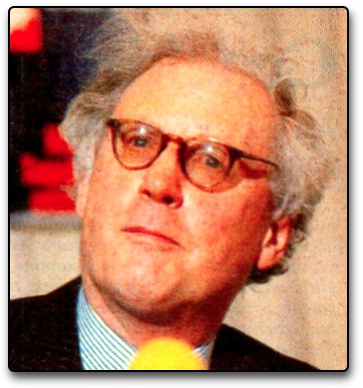

Newsweek sent Gerhard Weinberg of the University of North Carolina.

Historian Hugh Trevor-Roper

Trevor-Roper arrived first, on April 8, 1983. Trevor-Roper, as author of

The Last Days of Hitler, was one of the most famous Hitler experts in the world, even though his formal area of academic expertise was 16th and 17th century British history.

The Last Days of Hitler, published in 1947, was his account of "Operation Nursery" -- an official British government investigation, that he had been charged with leading, into the fate of Hitler. The British had commissioned this investigation immediately after the war in order to confront persistent rumors that Hitler had survived. Trevor-Roper, after exhaustive investigation, concluded that Hitler had committed suicide. The book made him famous, and established his reputation as a Hitler expert.

When Trevor-Roper first learned of the Hitler diaries he was skeptical. He knew that a large number of forgeries circulated in the blackmarket for Nazi memorabilia. He also knew that Hitler famously disliked writing in his own hand. Nevertheless, by his own account, once he saw all the volumes of the diaries displayed before him, his doubts weakened. Rapidly, he became a believer.

In an article written soon after for the London

Sunday Times, Trevor-Roper described how it was the sheer volume of material that won him over:

"letters, notes, notices of meetings, mementoes, and, above all, signed paintings and drawings by Hitler, all covering several decades -- which convinced me of the authenticity of the diaries. For all belong to the same archive, and whereas signatures, single documents, or even groups of documents can be skillfully forged, a whole coherent archive covering 35 years is far less easily manufactured."

Trevor-Roper also claimed that

Stern told him the paper had been chemically tested and that they knew the identity of the german official who supplied the diaries. Both claims were false. But based upon these assurances, Trevor-Roper gave his stamp of approval to the diaries.

Gerhard Weinberg examined the diaries after Trevor-Roper, but he was likewise impressed by them. He noted that he thought it was significant that almost every page bore Hitler's signature. He felt that a forger would not have risked doing such a thing. Therefore, he also gave a prelimary opinion that they were real.

With assurances from two independent experts, the syndication negotiations proceeded. Talks with

Newsweek fell apart after

Newsweek balked at

Stern's aggressive demands, but

Stern was eventually able to ink a deal with Rupert Murdoch for over one million dollars. Rights were also sold to a variety of smaller foreign media corporations such as Paris Match and Grupo Zeta. All told,

Stern netted almost two million dollars, making it one of the largest syndication deals in history up to that time.

Announcing the Diaries to the World

Stern announced the existence of the diaries in a press release issued on Friday, April 22. Three days later it devoted a special issue of its magazine to the diaries. It was the biggest issue in the magazine's history, with a 48-page supplement devoted to the diaries. It had a print run of 2.3 million. The cover showed a picture of one of the diaries with the headline, "Hitler Diary Discovered."

The contents page of the issue in which Stern made the announcement.

The announcement generated worldwide coverage.

Newsweek devoted thirteen pages to the diaries, even though its deal with

Stern had fallen through, and the

New York Times ran articles about the diaries on its front page for four days in a row.

On Monday, April 25, in conjunction with the release of the special issue of the magazine,

Stern held a press conference in which it displayed volumes of the diaries for the media.

Stern intended the press conference to be an opportunity to boast about its scoop. It had prepared a film about the diaries and had prepared to have Trevor-Roper answer questions. But the press conference proved to be a disaster, giving an indication of things to come.

Instead of congratulating

Stern for its scoop, the reporters proved extremely skeptical, insistently raising questions about the authenticity of the diaries. Peter Koch, editor of

Stern, asked Trevor-Roper to address these concerns.

Unfortunately, during the previous week Trevor-Roper had grown increasingly uncertain about whether the diaries were, in fact, real. His doubts were reinforced when he learned that

Stern had lied to him about knowing the identity of the source of the diaries in East Germany. His response to the concerns of the reporters made the editorial staff of

Stern cringe:

"As a historian, I regret that the, er, normal method of historical verification, er, has, perhaps necessarily, been to some extent sacrificed to the requirements of a journalistic scoop."

The Diaries Debunked

Because of the disastrous press conference,

Stern decided that it needed to establish the authenticity of the diaries once and for all. It arranged for the Bundesarchiv (the federal archives of West Germany) to examine three complete volumes of the diaries. This was the beginning of the end for

Stern.

On May 1 the Bundesarchiv presented them with the results of its testing. Chemical analysis indicated the diaries were fake. The report stated, "All three volumes contained traces of polyamid 6, a synthetic textile invented in 1938 but not manufactured in bulk until 1943."

Panicked,

Stern handed fifteen more volumes over to the Bundesarchiv for examination, hoping that perhaps only a few of the diaries were fake. There was no such luck. On Friday May 6, 1983 the Bundesarchiv delivered its final judgement: All the diaries were fake.

Evidence of Forgery

The Bundesarchiv was devastating in its analysis of the diaries. They declared them to be clumsy, almost amateurish forgeries.

Physically, it was clear the diaries were fake. The whitener and fibers in the paper were of postwar manufacture. The labels, supposedly spanning thirteen years, had all been typed on the same machine. The Bundesarchiv determined that the Hess volume had been written within the last two years, and the 1943 diary was less than twelve months old. The ink came from an ordinary artist's shop. And at least one set of the initials glued on the front of the diaries was made of plastic.

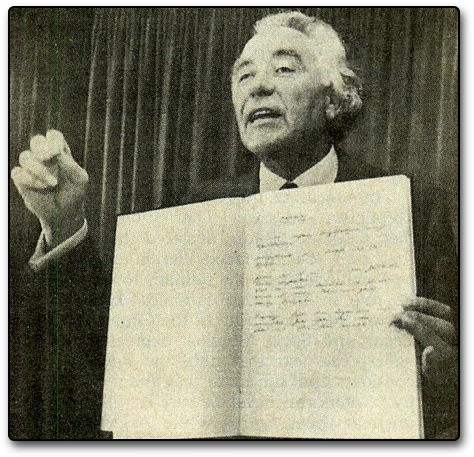

Hans Booms of the Bundesarchiv delivers the verdict: The diaries are fake.

The content of the journals was also a giveaway. The entries contained historical inaccuracies and many of them had been plagiarized from Domarus's

Hitler's Speeches and Proclamations (Kujau's favorite source). Hans Booms of the Bundesarchiv commented:

"It became apparent to us that if there was nothing in Domarus for a particular day, then Hitler didn't write anything in his diary that night either. When Domarus did include something, then Hitler wrote it down. And when an occasional mistake crept into Domarus, Hitler repeated the same error."

Faced with this evidence, there was nothing

Stern could do but admit it had been hoaxed.

Aftermath

The announcement that the Hitler Diaries were fake made front-page news around the world. Heidemann quickly told all he knew, but insisted he had believed the diaries were real. Kujau, however, fled to Austria. But when he learned that Stern had paid nine million marks for the diaries, whereas Heidemann had paid him only slightly over two million, he became so infuriated that he decided to give himself up, just to spite Heidemann.

On May 26, Kujau confessed. To prove his guilt, he wrote out part of his confession in Hitler's handwriting. He also claimed that Heidemann had known all along that the diaries were fake.

Reeling from the embarrassment of the Hitler diaries debacle,

Stern underwent an editorial shake-up. The two top editors, Peter Koch and Felix Schmidt, were forced out, although they were given a generous compensation package for leaving. None of the management team at Gruner and Jahr faced any consequences at all, despite having been the driving force behind Stern's involvement with the diaries.

In August 1984 Heidemann and Kujau were put on trial. Heidemann was accused of stealing 1.7 million marks from Stern, and Kujau of receiving 1.5 million for the diaries. This left over five million marks unaccounted for. To this day, no one is sure what happened to that money, though it is suspected Heidemann somehow managed to spend it. Both men were convicted of fraud and sentenced to over four years in prison each.

All told,

Stern is believed to have lost close to 19 million marks because of the hoax. This included the money it paid for the diaries, the bonuses it gave to Heidemann, the compensation given to the sacked editors, the costs of canceling the subsequent special issues devoted to the diaries, and other miscellaneous costs.

Conspiracy Theories

Many believed the Hitler Diary forgery was too elaborate to have been perpetrated by Kujau alone. This has given rise to a number of conspiracy theories.

• In December 1983 the

Sunday Times suggested that the hoax was organized as a fund-raising operation to pay the pensions of former members of the SS.

• Radio Moscow claimed that the CIA was behind it all. It alleged the CIA planned to use the hoax to divert attention away from the deployment of new US missiles in Germany.

• The East German government was immediately suspected of having some involvement in the hoax. There was talk of the diaries having been produced in an East German "forgery factory." New life was breathed into this theory in 2002, when Gerd Heidemann's Stasi file was released, revealing that he had been recruited by the East German intelligence service in 1953. He had been paid to provide information on "military targets and secret service premises, in particular those of the English [sic] secret service". The files indicated that Heidemann was still active in the service until 1986. However, it is not clear if his role in the service had anything to do with his participation in the Hitler Diary hoax. Heidemann himself claimed to be a double agent working simultaneously for the West German authorities. He claimed that he handed over all the money he received from the East Germans to the West Germans.

Postscript

After being released from prison in 1988, Kujau opened a gallery in Stuttgart. There he sold "authentic fakes." These included not only forgeries of Hitler's paintings, but also reproductions of Dalis, Monets, Rembrandts, and Van Goghs. He signed each painting with both his own name and that of the original artist. Many of these "authentic fakes" sold for tens of thousands of marks. In fact, his work became so popular that other forgers began to create forged copies of Kujau's forgeries.

Kujau tried to use his celebrity status to pursue a political career. In 1994 he ran for mayor of his home of Löbau. Two years later he ran for mayor of Stuttgart. Both campaigns were unsuccessful.

When he was released from prison, Kujau had indicated his intention to write a memoir of his role in the Hitler Diary hoax, to be titled

I Was Hitler. However, he never found the time to write this. In 1998 a book appeared in print under his name titled

Die Originalität der Fälschung ("The Originality of Forgery"). But Kujau denounced this book as a fraud, stating, "I did not write one line of this book."

Kujau died in 2000. His great-niece, Petra Kujau, was subsequently charged with selling hundreds of fakes of his fakes. She would buy oil paintings from art schools in Asia, usually for as little as 10 euros apiece, write Kujau's signature on them, and resell them for up to 3,500 euros.

In 1991 Thames Television broadcast a five-part TV series about the Hitler Diary hoax titled

Selling Hitler, based upon the book by Robert Harris of the same name. The drama featured Jonathan Pryce as Gerd Heidemann, Barry Humphries as Rupert Murdoch and Alexei Sayle as Kujau.

Links and References

- Harris, Robert. (1986). Selling Hitler. Faber and Faber.

- Magnuson, Ed. (May 16, 1983). "Hitler's Forged Diaries." Time: 36-47.

- Hooper, John. (July 29, 2002). "Hitler diaries man was a spy." Guardian.

- West, Patrick. (Jan. 22, 2001). "Faking it big in the 21st Century." New Statesman.

- "Konrad Kujau." (Sep. 14, 2000). The Times (London).

- Hamilton, Charles. (1991). The Hitler Diaries: Fakes that Fooled the World. University Press of Kentucky.

- Crossland, David. (April 22, 2006). "This may look like a fake Mona Lisa. It isn't. It's a fake of a fake Mona Lisa." Times Online.

- Kujau Archive. Website of Konrad Kujau.

Comments

There also is a german comedy (yes,they do exist) called "Sthonk", which quite accurately portrays the whole affair, only the names were changed.Most of the Info in this article is shown, even the bit with the false initials on the book covers, in the movie someone notices it, but they dismiss it as meaning "Führer Hauptquartier", which is obviously wrong.Heidemann is characterized as a bit slimy and greedy while Kujau is portrayed as a likeable smalltime crook, who got in over his head. My favorite scene is when Kujau delivers a freshly finished painting of a nude Eva Braun (for which his lover posed) to "Steifel". But Steifel has an expert at the ready who knew Hitler personally. Kujau is very nervous, he thinks all is up, but then the "expert" declares that he remembers the painting, that he even was present, when it was done, which leaves Kujau quite baffled and stunned by his good fortune.I dont know if there are any english versions of the movie, but its worth checking out.