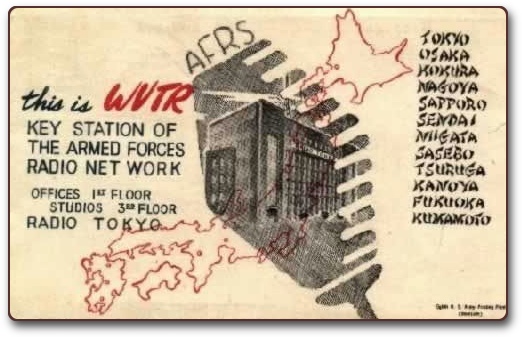

On May 29, 1947, the armed forces radio station in Tokyo, WVTR, interrupted its evening broadcast of dance music with a disturbing news bulletin: a 20-foot sea monster had emerged from the waters of Tokyo Bay and was making its way inland. The entire region was said to have been thrown into chaos.

For the next hour, a series of bulletins updated listeners on the progress of the "dragon" as it proceeded downtown, derailing trains and smashing buildings.

Troops were said to be battling it, although bullets were useless against it. So instead soldiers were using flamethrowers, grenades, teargas, and phosphorous bombs.

Listeners were advised to barricade themselves indoors and to keep phone lines clear for emergency calls.

One listener later recalled that the reports "continued at a frantic pace, included harrowing rescues and escapes, remote radio links, movement of Heavy Weapons and Tanks and all of the stuff of which the truly epic stories are made. Accompanied by the terrifying screams, roars and shrieks of both the beast and the panic stricken populace. As well as the gun fire and bullhorns of the protectors."

Finally, the monster reached downtown Tokyo. An announcer, identified as Cpl. Jim Carnahan of Chicago, who was providing a play-by-play account of the battle, then told listeners he would "draw nearer the beast."

He did so, at which point the monster stopped, turned, and addressed the listeners in a soprano voice. It said that it wished to congratulate the Armed Forces Radio Station on its fifth anniversary.

Response

The hour-long broadcast was intended as a joke in honor of the station's fifth anniversary, but this was lost on many of the listeners who took it seriously. In fact, the broadcast caused widespread panic.

As the broadcast progressed, the phone lines of the station soon were tied up by people seeking more information. Military police were put on alert, and Japanese police were told to stand by to fight the monster.

But during the program, the station personnel declined to respond to requests for more information, which fueled the uncertainty.

As soon as the program ended, it was revealed to be a joke and listeners were asked to stop telephoning the radio station, army headquarters, or any other official agency. These explanations continued until the station went off the air that night. But alarmed queries were being received as late as 14 hours later.

Among those who called was an officer from the British occupation troops who said his men were demanding rifles and grenades so that they could go and join the battle against the monster.

One GI telephoned to say that he had personally seen the monster, which he described as a horrifying, thick-skinned creature that grinned "in an oily and slimy manner."

Even Gen. MacArthur himself was said to have been fooled and to have had a member of his staff call the station.

The broadcast had the greatest effect on members of the U.S. Armed Forces and their families. There were few reports of English-speaking Japanese listeners being alarmed by the broadcast.

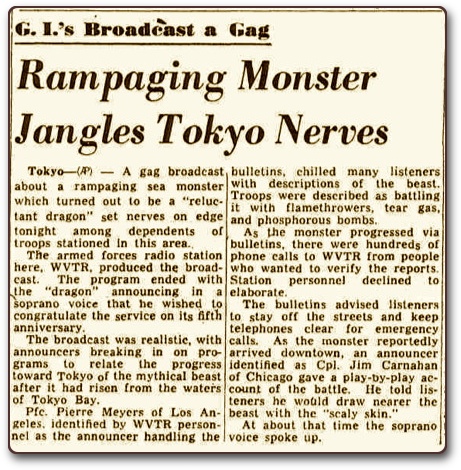

Binghamton Press

Binghamton Press - May 29, 1947

Repercussions

The military authorities were not pleased by the broadcast.

Soon after the program ended, counter-intelligence officers arrived at the station and informed the officer in charge that "there'll be repercussions and they will start from the top on down."

There were two main issues that angered the military. First, no one at the station had told any authorities beforehand of their intention to stage such a stunt. The radio staff later explained that doing so would have "ruined the surprise."

Second, WVTR was considered a particularly inappropriate outlet for such a joke because the station was the official mouthpiece for directives from Gen. MacArthur to English-speaking Japanese.

The day after the broadcast, five men at the station were relieved of their duties, pending an investigation. These were Capt. James B. Teer (commanding officer of WVTR), Cpl. Arthur Bartick and Pfc. Arthur Thompson (authors of the script), Dr. Wilton Cook (the civilian program director), and Pfc. Pierre Meyers (the announcer who read the bulletins).

A number of these men were reportedly later transferred to Korea as their punishment.

Godzilla

In 1954, the film

Godzilla debuted in Japan. The storyline of the movie had close parallels to the 1947 broadcast. Both described a gigantic dragon-like monster rising from Tokyo Bay and wreaking havoc on the city.

The similarities between the two have led some to suggest that the 1947 broadcast inspired the

Godzilla movie. This is possible. However no one involved in the production of

Godzilla ever credited the WVTR broadcast as an inspiration.

What was credited as a direct inspiration for

Godzilla was the 1953 American monster movie

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms which, in turn, was partially based on a 1951 short story by Ray Bradbury.

So it's unlikely that there was a direct connection between the 1947 broadcast and 1954's

Godzilla. But perhaps the makers of

Godzilla had a vague memory of a night in 1947 when a giant monster attacked Tokyo, and on a subconscious level this developed into the story for the film. Or perhaps it's a case of different people independently coming up with a similar story idea.

Links and References

- "WVTR's Sea Monster," Ernest L Gunerious. Radio Heritage Foundation.

- "Army radio gag scares listeners," (May 30, 1947). Schenectady Gazette.

- "Rampaging Monster Jangles Tokyo Nerves," (May 29, 1947). Binghamton Press.

- "Tokyo radio hoaxers face exile in Korea," (Jun 1, 1947). Los Angeles Times.

Comments