The History of April Fool's Day

An illustrated exploration of the tradition of April Foolery

An illustrated exploration of the tradition of April Foolery

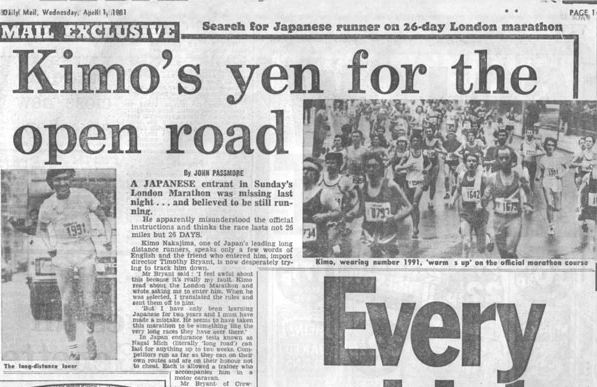

5. The Era of Tall Tales

During the nineteenth century, hoaxes came to play a large role in the newspaper industry. The trend started with the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, in which the New York Sun claimed that life had been discovered on the moon (and then discovered that a clever hoax could sell a lot of papers), and culminated in the era of yellow journalism when hoaxes and falsehoods mixed almost indiscriminately with real news in daily reporting. So it was a natural progression for newspapers to start playing hoaxes on their readers on April 1st, since they were already perpetrating hoaxes throughout the rest of the year anyway. We find media April Fools from as early as the 1840s, when the Boston Post announced that a cave full of treasure had been discovered beneath Boston Common, causing a huge crowd to descend upon the Common in a fruitless quest to see this spectacular sight.

However, it was in the latter half of the nineteenth century that the tradition of playing April Fool hoaxes on readers firmly took hold among newspapers. The model for these hoaxes was the tall tale — a literary genre that had greatly risen in stature during the nineteenth century, popularized by writers such as Mark Twain. The goal was to get readers (and hopefully rival papers) to swallow the most ridiculous story possible.

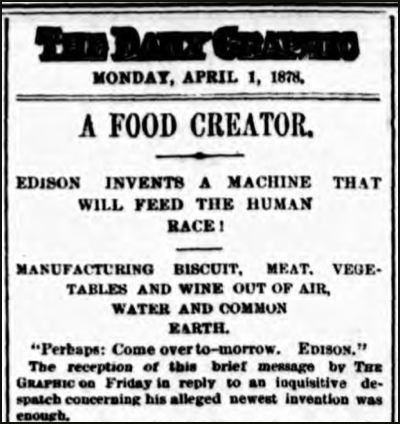

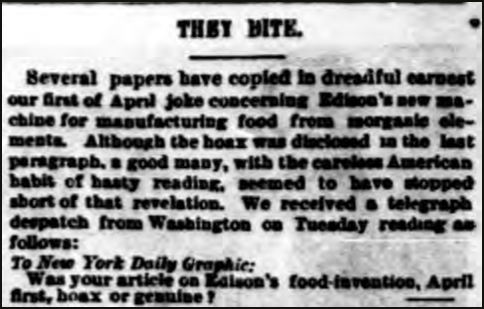

A celebrated example occurred on 1 April 1878, when the New York Graphic revealed that Thomas Edison had invented a machine that could transform soil directly into cereal and water directly into wine, thereby ending the problem of world hunger. Newspapers throughout America fell for the story, repeating the claim and heaping lavish praise on Edison. In response, the Graphic printed a simple, gloating headline: "THEY BITE".

Above: The New York Graphic's April Fool story.

Below: Its gloating gotcha.

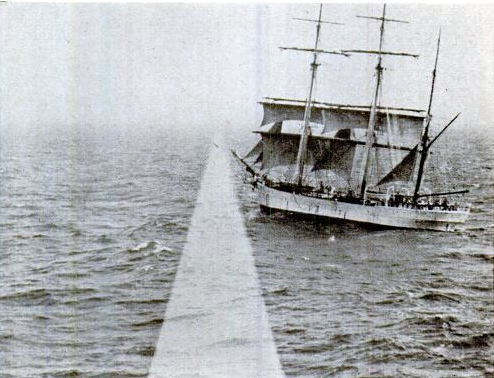

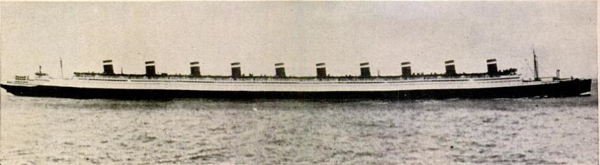

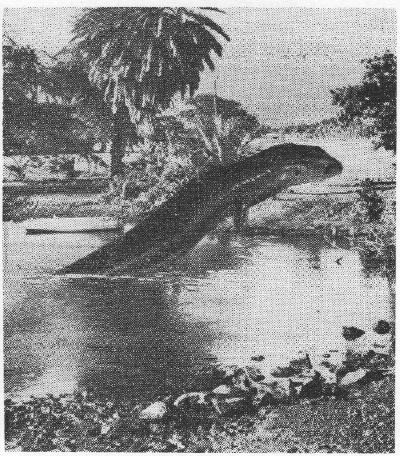

Tall-Tale April Fool Photography

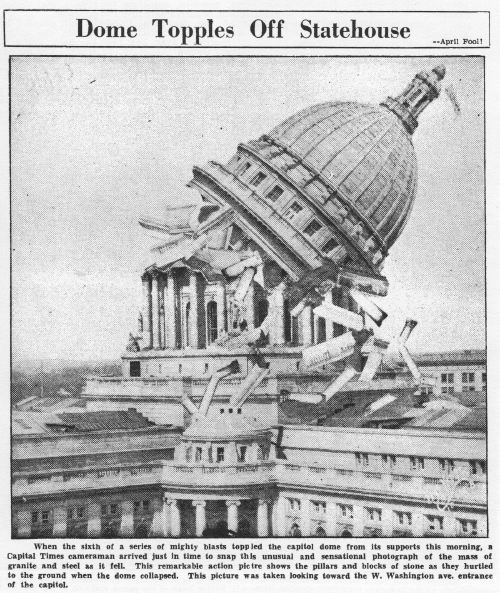

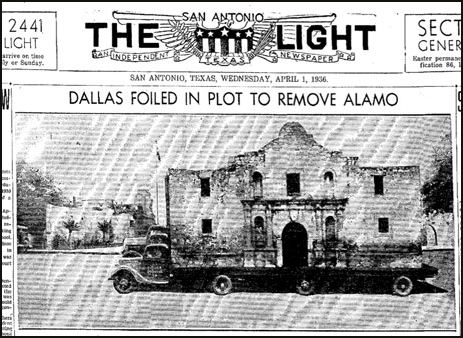

In 1894, the first photo postcards were introduced. They were an immediate success, because tourists loved to be able to send a photo of where they had been back to friends and family. Photo postcards, in turn, soon created a market for a new photographic genre — the visual tall tale. Working in their darkrooms, photographers altered photos in humorous ways to create impossible images such as corn as big as trees or cabbages larger than barns, and then they sold these images as postcards. These "trick" or "freak" postcards, as they came be known, were extremely popular with consumers, and those photographers (such as William 'Dad' Martin) who were particularly skilled at the art of making them grew quite wealthy.During the 1920s, German newspapers, inspired by the 'freak' postcards, began creating joke images that they ran on April 1. Readers loved them, and thanks to the launch of wirephoto services in 1921, the joke photos were rapidly disseminated and reprinted in papers throughout Europe and America. Sometimes the non-German papers didn't realize the photos were jokes and ran them as serious news. By the 1930s, the practice had spread beyond Germany and became particularly popular with the many small newspapers in America serving regional markets. (The larger papers, such as the New York Times, considered such unsophisticated humor to be beneath their dignity.)

These April Fool photos very much took the form of "gentle nonsense" (to use the phrase of historian Curtis MacDougall). Many of the pictures were so silly that they were scarcely believable, even by the standards of the time. They were intended to be no more than jokes in visual form, offering readers a bit of light diversion every April first.

April Fool's Day on TV

The Tradition Continues

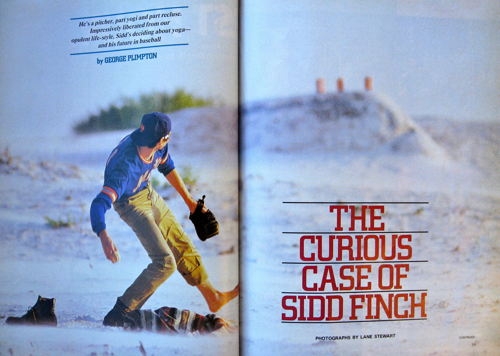

1985: Sidd Finch

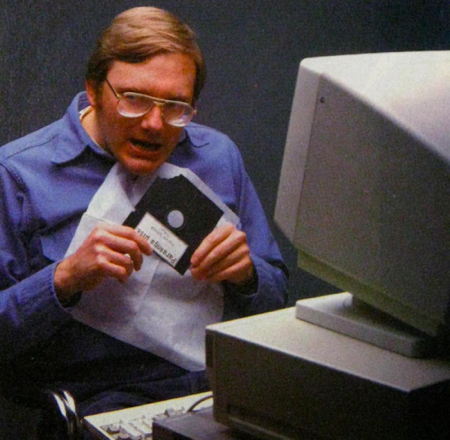

1985: Edible computer disks

2009: Tartan Sheep that appeared in the London Times

All text Copyright © 2014 by Alex Boese, except where otherwise indicated. All rights reserved.