The History of April Fool's Day

An illustrated exploration of the tradition of April Foolery

An illustrated exploration of the tradition of April Foolery

Introduction

It's a day when you have to be on your guard against whoopee cushions, coins glued to pavements, wild goose chases, and bizarre stories in the news about spaghetti-growing trees and left-handed hamburgers.

Truth be told, most people ignore the day, assuring themselves that they're far too mature for such foolishness, but a dedicated core of folly-loving pranksters keeps the tradition alive.

But even those who ignore the day might wonder why such a celebration exists. How did the tradition originate? How has it changed over the years? And why would our reason-loving culture set aside a day in honor of folly?

The following pages attempt to provide some answers, delving deep into the history of April foolishness, tracing its evolution from ancient prank-filled festivals and medieval fools all the way up to the hoaxes of the internet age.

Part 1: Foolishness Before 1500 ad

1. The Beginning — Ancient Prank-Filled Festivals

If we look back two thousand years or more, we find no trace of April Fool's Day. But what we do find is celebrations in cultures around the world that very much resembled April Fool's Day, because they all centered around the playing of pranks. The ancient Romans played pranks during both the festival of Saturnalia (at the Winter solstice) and Hilaria (at the beginning of Spring). In India there was Holi, known as the festival of color, during which street celebrants threw colored powder and water at each other. Iranians played jokes on each other on Sizdah Bedar, at the beginning of April — a tradition that dates back to the sixth century BC (and continues to this day). In ancient Korea, it was the custom to play pranks on the first day of snowfall. And the millenia-old Jewish festival of Purim, at the start of spring, was a time of satire and frivolity.

Could April Fool's Day trace back to one of these celebrations? Although it's tempting to speculate about such a direct lineage, there's no evidence this is the case. Instead, what unites April Fool's Day with these earlier prank-filled festivals is that they all demonstrate what appears to be a universal cultural phenomenon — the impulse to play pranks at times of transition in the calendar, when an old season or year is ending, and a new one is beginning. Thus, in cultures everywhere you find people playing pranks at the onset of winter or the arrival of spring. Trick-or-treating on Halloween is an example of the phenomenon. And April Fool's Day, likewise, occurs at a time of seasonal transition, falling on the first day of the first month of spring (or what was widely regarded as the first month of spring during the middle ages).

Similarly, it's common for people to have pranks played on them at times of transition in their lives, such as when they're getting married (think of tying tin cans to the back of the married couple's car), when they've started school (freshmen hazing), and when they've started a new job.

The question is, why do times of transition inspire pranks? One theory offered by sociologists is that pranks give expression to the nervous energy and tension associated with change. They defuse the tension through humor, providing it with a safe outlet.

Another theory, suggested by the folklorist Alan Dundes, is that pranks serve as miniature rites of passage, mirroring the larger rite of passage occurring in the person's life, or in the natural world. During a prank, the victim is first symbolically separated from the group, goes through a trial, and is then brought back into the group. Dundes explains, "either the dupe comes to realize that he has been fooled or the joke is revealed to the victim by one or more members of the group. At this point, the victim is re-incorporated into the group, e.g., as a full-fledged member in good standing."

Finally, pranks might be associated with times of transition because they represent a symbolic reversal of the social order. Normal expectations are turned upside-down. Truth becomes fiction. The young challenge the authority of the old. Trust is replaced by suspicion. This mirrors the reversal occurring either in the natural world (winter becoming spring) or in the person's life (a single person becomes married, etc.). But at the conclusion of the pranks, the normal order returns and is reaffirmed.

The Roman festival of Saturnalia, held in late December, involved extravagant public banquets, as depicted in this 18th-century painting titled "Winter or Saturnalia" by Antoine-François Callet.

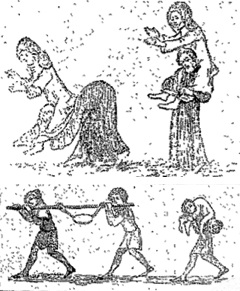

During Saturnalia, social customs were temporarily reversed. Masters had to serve slaves, and even carry them around, as depicted in this illustration by J.R. Weguelin, published in Harper's Magazine, Dec. 1884.

|

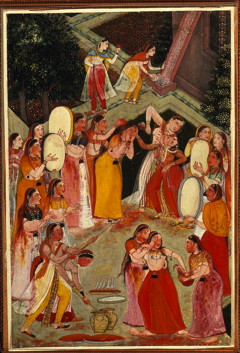

Girls spraying each other with colored water at Holi. Rajasthani, Bikaner school. Circa 1640. Holi originated as a spring harvest festival in northern India. The custom dates back to ancient times, although its exact age is unknown.

Holi remains enormously popular today. This image of Holi celebrants was taken in Gauhati, India on March 15, 2006.

|

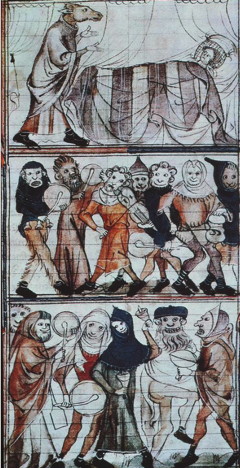

A 14th century depiction of charivari, which was the medieval folk custom of making noise, parading through town in masks, and playing pranks during weddings. The modern tradition of pranks at weddings derives from this custom. Charivari became particularly raucous when people disapproved of the wedding, such as when an old man was marrying a very young woman.

|

2. The Medieval Fool and the Culture of Folly

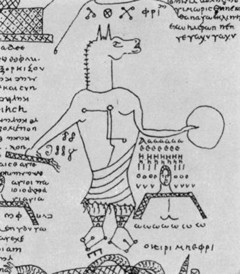

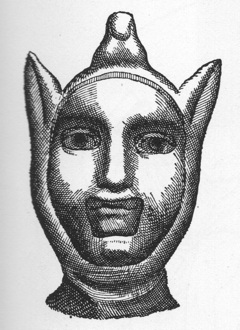

April Fool's Day, by its name, honors the fool — that curious figure who wears a multi-colored tunic, bells, and a pointed hat. Fools have disappeared from the modern world (though, of course, we still have many foolish people), but back in the Middle Ages they played a central role in European culture. The fact that we still have a celebration in their name demonstrates just how prominent their presence used to be. In this sense. April Fool's Day is like a small fragment of the medieval world that continues to persist into the present.The roots of the fool go far back in time. Their characteristic dress probably evolved from the costumes worn by comic actors back in ancient Rome — and those costumes, in turn, may have derived from ancient Egyptian trickster figures. But it was during the Middle Ages that the fool, as a concept and iconographic image, fully came into his own.

Who were the fools?

'Fool' was a broadly applied term that included a wide range of people. Some fools were wandering entertainers who made a precarious living traveling from town to town, always on the road. Often these entertainers were either monks who had abandoned their monasteries or scholars who had dropped out of university.

But the term also included those who today we would describe as mentally handicapped, as well as people with physical differences such as hunched backs, dwarfishness, and even ugliness.

In fact, the term 'fool' encompassed almost anyone on the margins of society who, for one reason or another, didn't quite fit in. Sometimes a distinction was made between "natural fools" (i.e. the mentally handicapped) and "artificial fools" (purposeful comedians). But during the Middle Ages the distinction wasn't applied as often as, to us, would seem to make sense. More often, 'fool' was used as a catch-all category for anyone who was different.

Some fools found employment in royal courts, but overall court fools were a small subset of the larger group. And during this period, court fools were most likely to be "natural fools" who people laughed at, not with.

The fool as a symbol

Fools were real people, but the fool was also a symbolic character that frequently appeared in medieval art and literature. However, the qualities attributed to him, as a symbol, varied greatly. Sometimes the fool represented holiness and innocence — a reminder that God accomplished his purposes through the foolish and humble, not the great and powerful. Followers of St. Francis of Assisi, for instance, proclaimed themselves to be "the fools of Christ."

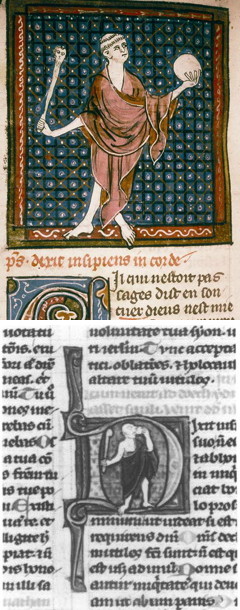

But at other times, the fool represented depravity and impiety. He was the foolish denier of God. It was common for images of fools to appear in illuminated manuscripts accompanying the opening line of psalms 14 and 52: "The fool has said in his heart, there is no God." Historian D.J. Gifford has noted that the further back in time we look, the more often we find this sinister version of the fool. Twelfth-century images of fools typically portrayed them as shabby, poor, half-naked, and bald — a far cry from the merry jester image of modern times.

These contradictory meanings stemmed from the fool being the physical manifestation of folly itself which, in medieval folk belief, was a fundamental aspect of the natural world. Folly was the teeming chaos that lay beyond the safety of human institutions and traditions. It was unstructured primeval energy — an unpredictable force of either creation or destruction. By tapping into this energy, the fool could be a conduit for either angelic or demonic divinity.

As such, the fool was very much a religious symbol. Or, as sociologist Anton Zijderveld puts it, a "magico-religious" symbol. Because although the fool was incorporated into Christian thought, he nevertheless represented a pre-Christian, magical view of the world. As Zijderveld also notes, the medieval celebration of folly was "an excellent medium for the expression of ancient paganism."

The Egyptian god Seth

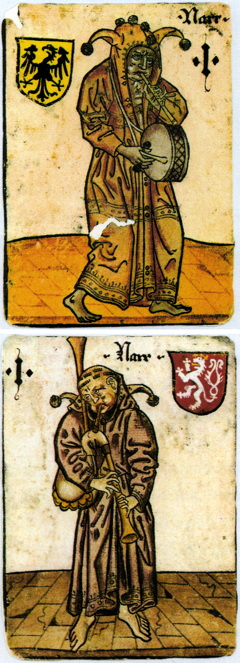

15th century cards showing fools.

|

Detail from Roman terracotta showing a comic actor wearing a hat resembling those later worn by fools.

A "natural" fool

|

Dixit insipiens. The unholy fool.

A dancing fool

|

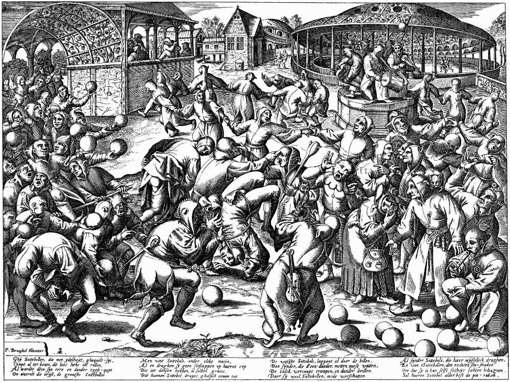

3. The Feast of Fools

The Feast of Fools.

|

{title}.

|

All text Copyright © 2014 by Alex Boese, except where otherwise indicated. All rights reserved.