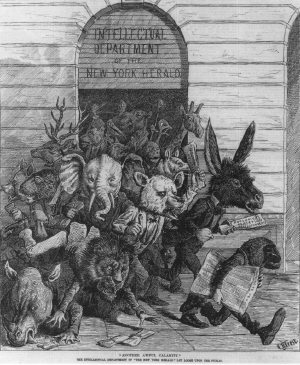

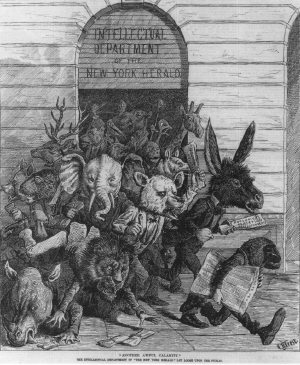

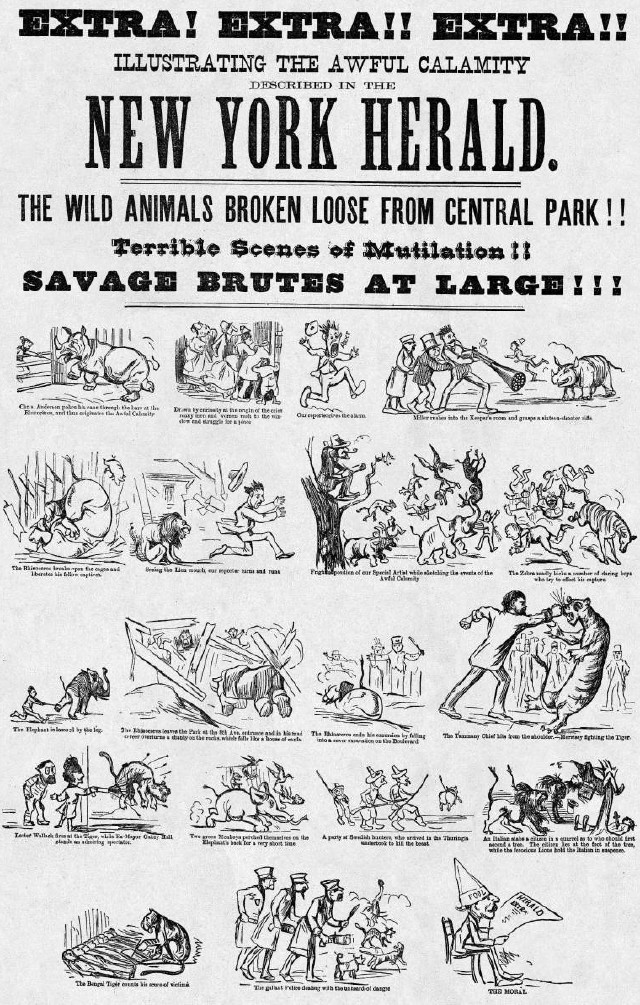

"Another Awful Calamity. The Intellectual Department of The New York Herald Let Loose Upon the Public."

"Another Awful Calamity. The Intellectual Department of The New York Herald Let Loose Upon the Public." Front cover of the

Daily Graphic (Nov. 13, 1874), mocking the

Herald for its recent wild animal hoax. Illustration by Arthur Burdett Frost.

In the 1870s the New-York Herald was one of the most widely read and influential papers in the world. It had recently won international acclaim when it financed Henry Stanley's successful quest to find Dr. David Livingstone in the interior of Africa. But it followed up this success with a stunt that was almost as widely denounced.

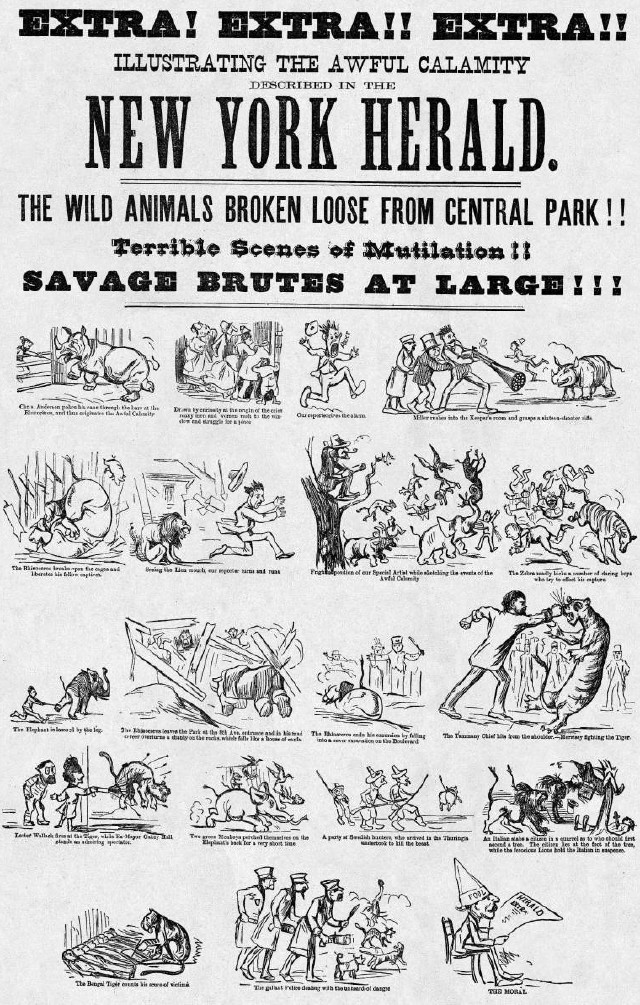

On November 9, 1874 the Herald published a front-page article claiming that the animals had escaped from their cages in the Central Park Zoo and were rampaging through the city. A lion had been seen inside a church. A rhinoceros had fallen into a sewer. The police and national guard were heroically battling the beasts, but already forty-nine people were dead and two hundred injured. It was "a bloody and fearful carnival," the article despaired. And the animals were still on the loose! (

Click here to read the full text of the New York Herald article.)

Many readers panicked when they read the article. However, those who did so hadn't read to the end where it stated (in rather small print) that, "the entire story given above is a pure fabrication."

Along with the

Great Moon Hoax of 1835, the New York Zoo Escape ranks as one of the most notorious media hoaxes of the nineteenth century.

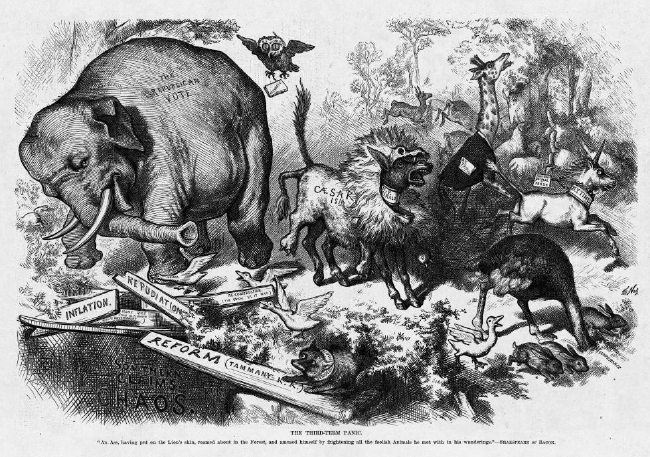

An illustration that accompanied an 1893 article in

Harper's Weekly about the hoax.

Authorship

Thomas Connery, an editor at the

Herald, later confessed in an article published in

Harper's Weekly in 1893, that the idea for the hoax had been his. He insisted that James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the owner of the

Herald, had not been responsible for it, although many assumed Bennett must have, at least, given it his approval.

Connery claimed that the idea for the hoax came to him after he witnessed a leopard almost escape while being transferred from an animal-carriage into its cage in the Central Park Zoo (referred to as the "menagerie" at the time). Wishing to call attention to the conditions at the zoo, Connery first thought of writing a column scolding the zoo keepers, but then decided that something more attention-grabbing was needed. He conceived of the idea of "a harmless little hoax, with just enough semblance of reality to give a salutary warning."

He first assigned the writing of the article to Harry O'Connor, but he felt that O'Connor's resulting piece was too obviously a "transparent imposition." Therefore, he reassigned the article to Joseph Clarke, who wrote the version that ran on November 9.

The Article

The article ran to over 10,000 words in length, and occupied six full columns. It appeared on page three, which was considered to be the front page. (The first two pages were always filled with ads and acted as a cover page for the paper.) "AWFUL CALAMITY," the headline screamed. "A Shocking Sabbath Carnival of Death."

The article began by offering general details of what it said had been a day of horror, beginning Sunday afternoon and continuing through Monday morning (November 9), when the article appeared. Because wild animals were supposedly still on the loose, it noted that the mayor had issued a proclamation urging all citizens "to keep within their houses or residences until the wild animals now at large are captured or killed."

The tragedy was said to have begun after a reckless keeper provoked a rhinoceros by prodding it with a stick through the bars. The enraged beast smashed down its cage, thereby escaping and killing its keepers. In its rage, it then battered down the cages of the other animals, who proceeded to scatter throughout the city, wreaking havoc wherever they went.

The text did not shy away from offering up all the gruesome details of the animal attacks:

Backing down from the mangled body with a swiftness almost incredible from his bulk, the rhinoceros plunged his horrid horn into the dead keeper...

The panther was crouched over Hyland’s body, gnawing horribly at his head. I recognized his body by the striped shirt which I could just see hanging tattered from the arm...

Men and women rushed in all directions away from the beast, who sprang upon the shoulders of an aged lady, burying his fangs in her neck and carrying her to the ground.

Scenes of increasing strangeness were described: a lion and a tiger fighting on fifty-ninth street, a battle between a sea lion and a rhinoceros, an anaconda attempting to eat a giraffe, Swedish hunters stalking a lioness on Broadway, a Bengal Tiger shot on Madison Avenue, a panther attacking worshipers inside a church on West Fifty-third Street, and carnage as a tiger leapt on board a ferryboat.

Specific names were given. A list of the dead and wounded was offered. And bolded column sub-headers highlighted all the most salient points: THE WILD ANIMALS ARE LOOSE, POLICE ARMED WITH REVOLVERS, CIRCLE OF FEAR-STRICKEN PEOPLE, CONFUSION AND DESTRUCTION.

Only if a reader read carefully to the end, would he have found the truth revealed in the final paragraph:

Of course the entire story given above is a pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true. Not a single act or incident described has taken place. It is a huge hoax, a wild romance, or whatever other epithet of utter untrustworthiness our readers may choose to apply to it. It is simply a fancy picture which crowded upon the mind of the writer a few days ago while he was gazing through the iron bars of the cages of the wild animals in the menagerie at Central Park.

The Reaction

By all accounts, the article caused widespread panic throughout the city. Armed men rushed into the streets, ready to defend their homes. Reporters were dispatched to cover the story. The police mobilized. Parents rushed to bring their children back from school.

Recalling the reaction nineteen years later, Connery wrote: "while in the hoax General John A. Dix was represented as shooting the Bengal tiger, in reality he did sally forth on the morning of the publication armed with a rifle, firmly believing that the Herald's story was true, and that danger might lurk at any corner."

Connery also claimed that the editor of the

New York Times ran out of his home waving two pistols in the air, ready to shoot the first animal he encountered.

The Hoax Denounced

Rival papers throughout the United States quickly and unanimously denounced the hoax. The New-York Times, while admitting that the "animals in the Central Park are confined in the flimsiest cages ever seen," described the article as an "intensely stupid and unfeeling hoax" and printed letters from readers claiming to have been terrified by the story. It commented sarcastically that if "charming sketches of dead children and dying old ladies do not move the reader to roars of laughter, his sense of fun must be somewhat different from that with which the proprietor or editor of the New-York Herald has been endowed."

The Galveston Daily News wrote: "To be in keeping with its enterprise, the Herald should bribe a keeper to let loose a lion or two upon occasion, so as to bring up that journal's prophetic record... Bennett had better recall Stanley from the interior of Africa. He is the crack lion shot of the Herald establishment, and should be at home to protect it."

The New York Times also reported that a group of citizens paid a visit to the District Attorney's office to express their outrage at the Herald's hoax and to find out whether the paper could be indicted on account of it. The District Attorney promised to give it his attention. However, no charges were ever brought against the paper.

For its part, the Herald feigned surprise when the article provoked such an enormous reaction, but it was wholly unrepentant. By way of apology, it simply inserted a short article into the next issue, titled "Wild Beasts," urging that safety precautions at the zoo be improved. Understandably, the public was underwhelmed by this show of contrition. However, the Herald did not report any drop in circulation as a result of the hoax.

Origin of the Republican Party Symbol

According to rumor, the Herald's wild animal hoax had an impact far beyond the controversy it temporarily stirred up. It may have been the inspiration for the elephant that serves as the symbol of the Republican party.

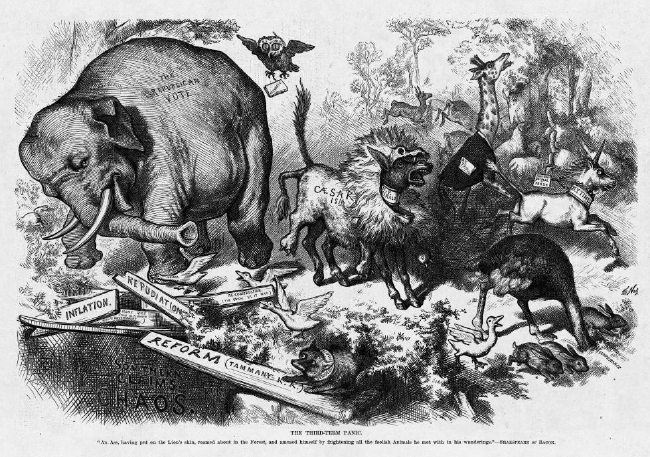

The link connecting the Herald's hoax to the adoption of the elephant as the republican party symbol was the political cartoonist Thomas Nast.

In 1874 the Herald was frequently editorializing against President Grant (a Republican), warning voters that he planned to seek a third term in office, despite the tradition, started by George Washington, that Presidents should limit themselves to two terms. The Herald charged Grant with "Caesarism." Republicans insisted that these charges were false.

The story goes that, in the week following the wild animal hoax, Nast (at the time a staunch Republican) published an illustration in

Harper's Weekly in which he satirized both the hoax and the Herald's attempts to scare voters about Grant's intentions. The illustration showed the Herald as a jackass, disguised in the skin of a lion tagged "Caesarism." The appearance of the Herald was scaring zoo animals who were running frightened through the woods of Central Park. One of the animals was an elephant labeled "The Republican Vote." The cartoon was captioned "The Third-Term Panic."

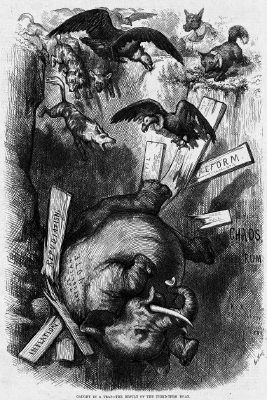

A few weeks later Nast returned to this theme, with a cartoon that showed the Republican Vote (again represented as an elephant) falling into a pit with a variety of other animals. The caption read, "Caught in a trap -- the result of the third-term hoax." The reference to the third-term hoax was a pun, alluding simultaneously to the Herald's charges of "Caesarism" and its recent wild-animal hoax.

Other cartoonists, inspired by Nast's cartoon, also began to use an elephant to represent Republicans, and so the symbol stuck. By the 1880s it was firmly established as the symbol of the party.

The link between the Democratic party and an ass (or donkey) traced further back, to the time of Andrew Jackson. But Nast's cartoons also helped to popularize that symbol.

This story of the origin of the Republican party symbol has been frequently repeated. For instance, William Safire tells it in his book

New Language of Politics (1972).

For the most part, it is true. Nast did publish these cartoons, and they did popularize the association of republicans with elephants. But the story is incorrect in one key detail. Nast's first cartoon (the one titled "The Third-Term Panic) was published a week

before the wild animal hoax, not after it. Therefore, the cartoon could not have been inspired by the hoax. In fact, some suggest the opposite is true -- that the hoax itself was inspired by Nast's illustration. This seems possible, but no one at the Herald ever commented on whether Nast's illustration served as a source of inspiration for them.

Links and References

- "Awful Calamity. Wild Animals Broken Loose from Central Park." (Nov 9, 1874). New York Herald.

- "Wild Beasts." (Nov 10, 19874). New York Herald.

- "Practical Jokes." (Nov. 10, 1874). The New-York Times.

- "The Heartless Newspaper Hoax." (Nov. 11, 1874). The New York Times.

- "A 'Herald' Sell." (Nov 15, 1874). The Galveston Daily News.

- Connery, T.B. (June 3, 1893). "A Famous Newspaper Hoax." Harper's Weekly. 534-535.

- Burns, Sarah. (1999). "Party Animals: Thomas Nast, William Holbrook Beard, and the Bears of Wall Street." American Art Journal. 30 (1/2): 8-35.

- Fedler, Fred. Media Hoaxes. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, 1989: 84-96.

- The Central Park Zoo Scare of 1874. bbc.co.uk.

- Cartoon of the Day. "The Third-Term Panic." Harpweek.com.

The Central Park Zoo Escape