In 1949, did a California restaurant worker really find a will sealed inside a bottle that bequeathed millions of dollars to him, as the finder of the bottle?

The story goes that on March 16, 1949, Jack J. Wurm was walking along a beach near San Francisco when he noticed a liquor bottle washed up on the sand. Jack was a man of modest means. He worked in the kitchen of a restaurant and lived in a small, rented house with his wife. However, his luck was about to change.

Jack noticed there was something inside the bottle. So he opened it up and removed a piece of brown wrapping paper on which the following message was written:

To avoid all confusion I leave my entire estate to the lucky person who finds this bottle and to my attorney, Barry Cohen, share and share alike.

Daisy Alexander - June 20, 1937

Jack hadn't heard of Daisy Alexander, so he thought the message was probably "a prank of some college kid." Nevertheless, he saved the bottle and message, and three months later told some friends at a party about his discovery.

One of his friends, a GI who had just returned from serving in England, immediately recognized the name. Daisy Alexander, he informed Jack, was the daughter of the sewing-machine magnate

Isaac Singer. From what he had heard, she had died in 1940 at the age of 80, injured by the blast of a German bomb that hit her London home. But more importantly for Jack, she had died childless, worth about $12 million, and without a will. Her lawyer believed she had written a will shortly before her death, but despite a highly publicized search for the document, he had been unable to find it. So the courts were unsure of how to dispose of her estate.

Jack's friend urged him to get in touch with Alexander's lawyer, Barry Cohen, and Jack promptly did this. He was unsure of the lawyer's address, so he sent a letter to the London postmaster asking him to forward his correspondence to Cohen, which the postmaster did. Soon Jack and the lawyer were in touch.

Jack sent a copy of the message-in-a-bottle will to the lawyer, who concluded that it appeared to be genuine. So Jack stood to inherit $6 million, his half of Alexander's fortune. He would get the money just as soon as a British court made everything official. Though this, of course, could take some time.

And that's how the story goes.

Good story, but is it true?

The tale of Jack Wurm's fortuitous discovery is a popular one. It's been told numerous times in newspapers, magazines, and on radio shows. It's the titular story in a book —

The twelve million dollar note: Strange but true tales of messages found in seagoing bottles

, by Robert Kraske (Thomas Nelson, Inc., 1977). And it's also often been used frequently in sermons (such as

here and

here). The lesson that the sermonizers derive from it is that if Jack Wurm had thrown away the seemingly ridiculous message, he would never have inherited anything. Likewise, they argue, people should not toss aside the Christian message of the Bible, no matter how ridiculous they think it sounds, lest they miss the great reward it offers.

However, the story has been questioned by skeptics. For instance, the

Kirkus Review of Kraske's book took the author to task for uncritically accepting the veracity of the tale, and questioned whether there even was such a person as Daisy Alexander:

Kraske appears to have collected clippings—many, of the column-filler sort—without necessarily checking them out. The titular story, for instance, tells of a San Francisco dishwasher whose lucky bottle bore a will naming the finder heir to the signatory's estate. And she, one "Daisy Alexander," was—his friend tells him—"the only child of Isaac Singer, the American sewing-machine millionaire." Now it happens that Singer had a notorious score of children and none of them was named Daisy. No wonder "at last report" in 1955 the twelve-million-dollar claim was still pending—where Kraske is content to leave it.

More recently, a

thread on the Snopes message boards questioned the story and concluded that it was an "urban legend." Similarly, the

Singer Memories website (about the history of the Singer Sewing Machine Company) has dismissed the story as a "persistent urban legend":

A persistent urban legend claims that Singer's granddaughter Daisy died intestate in England. Several years after her death a beach bum in San Francisco found a bottle with a note in it from Daisy, giving whoever found the bottle half her estate. Her lawyer, who would never otherwise have known of his good fortune, inherited the other half.

So is that it? Is the story nothing more than an urban legend? Well, not so fast. Yes, the story does sound urban-legendy, but investigation reveals that the skeptics may have been a bit too hasty. There are some questionable aspects to the story (someone was almost certainly perpetrating a hoax), but it's not an urban legend. The overall details of the story are true.

The Will of Daisy Alexander

Let's start with Daisy Alexander. Despite the doubts of the Kirkus reviewer, she definitely was a real person. She was indeed a daughter of Isaac Singer (not a granddaughter, as the Singer Memories site thought), and she was very wealthy.

Daisy Alexander's dress

Daisy appears to have been her nickname, which may have been what confused the Kirkus reviewer, even though it was the name she always went by. She married Capt. Granville Alexander, and the activities of the couple were often mentioned in society gossip columns. The

Victoria and Albert Museum now owns, as part of its fashion collection, a dress worn by Daisy Alexander as a young woman.

Capt. Alexander died in 1931. After this, Daisy retreated into her Grosvenor square mansion and became increasingly eccentric. Many sources report that she died in 1940, at the age of 80, when a German bomb exploded in the house next door during the Battle of Britain. However, a death notice in the

London Times reported that she died peacefully in her home on Sep. 20, 1939.

The Times, one has to assume, is correct. It's not clear what caused the later confusion about the circumstances of her death.

Death notice of Daisy Alexander - London Times, Sep 21, 1939

Daisy left behind an estate worth around £3 million ($12 million), which generated an annual income of $160,000. Barry Cohen had been her lawyer since 1908, and he knew he had drawn up "four or five wills" for her in the years before her death. However, when he went to look for them, he couldn't find any of them. They had disappeared.

Nor did he have copies. Whenever he had drawn up a will she had always instructed him to leave blanks for her to fill in later, because she didn't want anyone to know what they were getting before she died.

The only will he did have for her was an old one from 1909, but this will was problematic because it had a page ripped out of it, and it disposed of only a fraction of her estate.

So Cohen began a frantic search for the missing will (or wills). He was sure she must have hidden a will somewhere. But where?

During the war, the Ministry of Works took over Alexander's Grosvenor Square mansion. This complicated the search for the will, because the ministry didn't want a lawyer tearing up the place as people were trying to work. However, the ministry did allow Cohen to use a mine detector to scan the mahogany paneling of the house, in an attempt to find any hidden safes. This turned up nothing.

Cohen suspected that Daisy's former housekeeper, Mrs. Alice Sage, might know where the will was hidden, but he couldn't track her down.

Then the search for the will began to take a turn toward the absurd.

Daisy used to have a parrot named Bob whom she talked to for hours. Cohen thought that if he could find this bird, it might somehow lead him to the will. So a search for the bird ensued, but he never located it.

A spiritualist wrote to Cohen, informing him Daisy's ghost had told her that the will was hidden either in a tall black vase or a Louis XIV gilt settee. Cohen recalled that Daisy actually had owned such items, so he searched through antique shops to find them. He located the vase, but it was empty. He never found the settee.

A West African witch doctor offered Cohen his services as a will-finder. Cohen declined. Likewise, a member of a cult offered to use a secret pendulum device (a "Dawson's Pendulum") to locate the will. Again, Cohen turned the man down.

Finally, in desperation, Cohen hired Frederick Liston, a clairvoyant. Liston dipped his hands in water, in order to "magnify the electrical vibrations," and then ran his hands over various parts of the Alexander mansion, searching for the will. Unfortunately, he too turned up nothing.

Frederick Liston, London clairvoyant,

prepares to search for Daisy Alexander's will

In the meantime, word had spread about the search for the missing will and the increasingly strange methods being used to find it. In 1948 and early 1949, numerous papers ran stories about it. As a result of this publicity, new claimants for Alexander's money began popping up out of the woodwork. Long-lost relatives throughout upstate New York, where Isaac Singer had once lived, announced themselves to be the rightful heirs, plotting out convoluted genealogical patterns to back up their claims. Cohen generally ignored these would-be heirs.

And it was around this time that the hunt for the will took an unexpected twist, when Jack Wurm announced he had found Alexander's will in a bottle washed up on a San Francisco beach.

Jack Wurm's Discovery

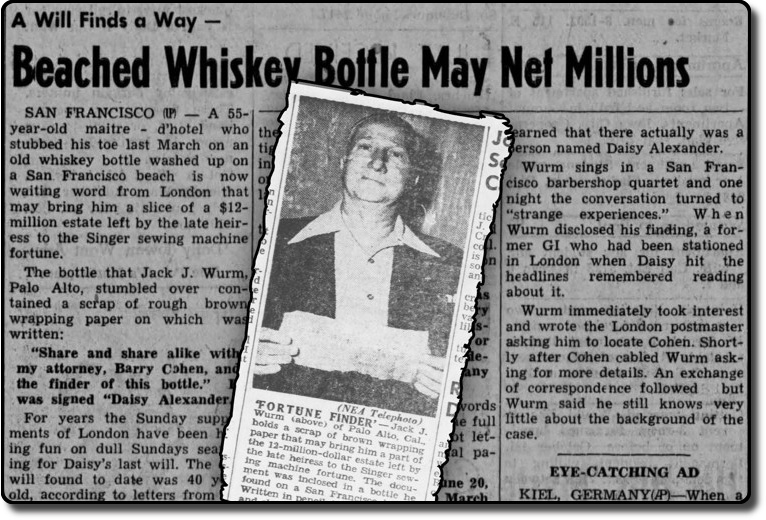

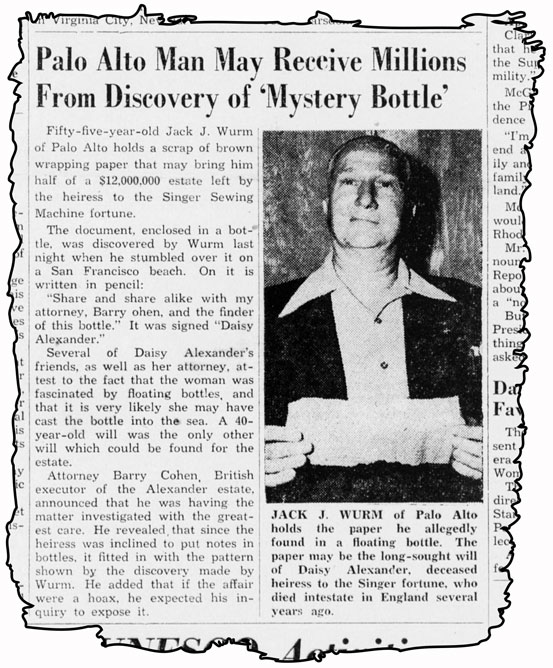

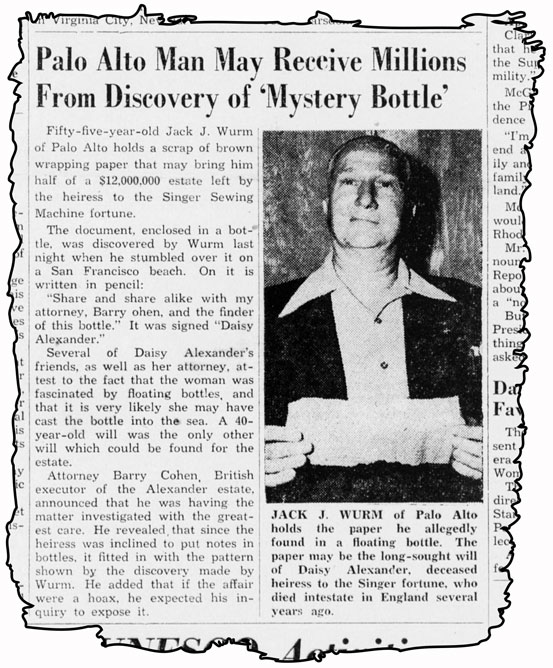

In July 1949, newspapers worldwide reported Jack Wurm's discovery of the bottle-borne will of Daisy Alexander. Wire services distributed a photo of him holding the document.

The Stanford Daily - July 29, 1949

Wurm notified Barry Cohen of his discovery. By this time Cohen was 84, and his son Ronald had taken over the day-to-day operations of the law practice that bore their name. But the elder Cohen still took an active interest in anything related to Alexander's will, and when he heard of the will in a bottle, he was intrigued. Surprisingly enough, he didn't dismiss it out of hand. In fact, he told reporters he thought there was a "good chance" it was authentic. He elaborated:

"It sounds fantastic, but she did have a curious interest in floating communications around in a bottle. I recall Mrs. Alexander talked in a fascinated manner about the distances bottles will float. But memory may be tricky and yesterday I asked Mrs. Alexander's old friend, Lady Stanley. She too recalled Mrs. Alexander was interested in floating bottles."

However, Cohen then immediately tempered his enthusiasm with legal reality. He noted that even if Daisy Alexander had written that will, placed it in a bottle, and thrown it into the Thames, and if the bottle had then found its way to San Francisco (presumably taking a northern polar route followed by a southern descent through the Bering Strait), that didn't mean that Wurm and himself were Alexander's legal heirs.

Cohen observed that the text of the will sounded "like somebody's attempt to write a will" rather than a genuine will. And more importantly, the signature on the document hadn't been witnessed. This meant that a British court would never accept it as a valid will.

Still, Cohen was curious enough about the will to want to examine it more closely. He obtained a photostat copy of the document from Wurm, in order to compare the signature to known samples of Daisy Alexander's handwriting. He also had the document microscopically examined, looking for any "code markings" that Alexander might have left on the document — markings that only her friends would understand.

Presumably he found nothing to convince him that the will was genuine, because in August 1949 Ronald Cohen announced that he and his father were no longer interested in the will that Wurm had found. He suggested that it "might even be a hoax."

Was the will a hoax?

It's possible that Daisy Alexander wrote the message the Jack Wurm found on a California beach in 1949. It's possible, but extremely unlikely. As Ronald Cohen indicated, the will was probably a hoax.

The circumstances of its discovery suggest this. First of all, if Alexander had tossed a bottle into the Thames, it seems farfetched to believe that the bottle would have floated all the way to San Francisco eleven years later (conveniently washing ashore near a major population center). Not impossible, but very improbable.

Second, the timing of the discovery is suspicious — the fact that Wurm found the bottle soon after the search for Alexander's will had been featured prominently in the news. This suggests that someone created the document after being inspired by the recent news stories.

So who created it? Who was the hoaxer?

We can pretty much rule out the Cohens. If they had wanted to create a fake will, they had the means to create something a lot more convincing (and something that courts wouldn't dismiss out of hand).

Wurm, as the man who claimed to have found the will, is the obvious candidate, although it has to be said that he doesn't seem like an obvious hoaxer. He came across in interviews as somewhat guileless and never did much to press his claim to Alexander's money. But then again, there is no standard pattern of what a hoaxer should look like. They come in all kinds of varieties.

Perhaps, as Wurm said he first suspected, the will was the "prank of some college kid" — or some other anonymous hoaxer. Perhaps someone in the San Francisco area read about the search for Alexander's will, put a fake will in a bottle and tossed it in the bay, where it was found soon after by Wurm.

Or perhaps Wurm was in collusion with someone else, someone who came up with the idea, created the will, and then convinced Wurm to pose as its finder, knowing that Wurm would come across as a believable character.

This final scenario seems the most likely to me, since Wurm just doesn't come across as the kind of guy who would have dreamed up such a fanciful scheme. And who could the colluder be? Wurm's GI friend who had served in Britain (the one who knew all about Daisy Alexander) has to be a prime suspect.

However, this is all speculation. Barring the discovery of new information, we'll never know for sure who the hoaxer was.

Postscript

After a flurry of news coverage in 1949, Wurm's discovery was mostly forgotten — until 1954, when reporter Alan Hynd decided to track down Wurm and find out the status of his million-dollar inheritance.

Wurm was still working in the kitchen of a San Francisco restaurant, and he didn't seem to have heard that the Cohens had long ago written off the will-in-a-bottle as a hoax. In fact, Wurm made it sound to Hynd as if the will was in some kind of legal limbo, with the possibility that a court might still declare it valid and make him an instant millionaire. Wurm said:

"I got a lawyer in San Francisco who's handling the whole thing for me and he keeps telling me not to worry. There's a lot of hurdles to go over when a guy like me just picks up a bottle on a beach in a foreign country and stakes a claim for millions just on the strength of a piece of paper in that bottle. I don't know what's been happening. To tell you the truth, I'm afraid to let myself think much about the matter."

Unfortunately for Wurm, by 1954 the fate of Alexander's estate had already been settled. A British court had granted probate for the 1909 will. Alexander's niece and nephew who lived in England became the primary heirs.

Eventually Wurm left San Francisco and retired in Minnesota. He died there in 1987, without ever having seen a dime of Alexander's money.

References

- Hynd, Alan. (Oct. 1954). "Tales of the Floating Bottles." The Saturday Evening Post. 27, 110-112.

- Kraske, Robert (1977). The Twelve Million Dollar Note: Strange but True Tales of Messages Found in Seagoing Bottles.

Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Thomas Nelson, Inc. - Menchin, Robert. (1963). The last caprice: A book of wills, odd and curious, of the famous and infamous

. Simon and Schuster.

. Simon and Schuster. - "Mrs. Alexander's Missing Wills Key to $12,000,000: Also seek settee with secret compartments and parrot named Bob," (Dec 6, 1948). The Milwaukee Journal.

- "Lost Will, $12,000,000 Estate Stumps London Searchers," (Dec 16, 1948). The Washington Post.

- "Sewing Machine Fortune - Will in a Bottle - Probate Attempts Abandoned," (Aug 6, 1949). Kalgoorlie Miner.

- "Will in Bottle May Be Authentic, Londoner Advises," (Jul 27, 1949). Spokane Daily Chronicle.

- "Microscope Expert To Examine Will," (Aug 3, 1949). Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Comments