|  |

| HOME | FORUM | REGISTER | LOGIN | HOAXIPEDIA | TOP 100 APRIL FOOLS | COLLEGE PRANKS | ABOUT THE CURATOR |

| A HISTORY OF HOAXES | HOAX WEBSITES | HOAX PHOTO TESTS | GULLIBILITY TESTS | TALL-TALE CREATURES | CONTACT |

About the Hoax Photo Database

The Hoax Photo Database catalogs examples of photo fakery, from the beginnings of photography up to the present. Included in the database are photos that are "real," but which have been suspected of being fake, as well as images whose veracity remains undetermined. The photos are displayed in chronological order (or reverse-chronological). They're categorized by theme, technique of fakery (if known), and time period. See below for the full list of categories.

Other viewing options

View database as Thumbnail Gallery, reverse-chronological or chronological.

The Hoax Photo Database catalogs examples of photo fakery, from the beginnings of photography up to the present. Included in the database are photos that are "real," but which have been suspected of being fake, as well as images whose veracity remains undetermined. The photos are displayed in chronological order (or reverse-chronological). They're categorized by theme, technique of fakery (if known), and time period. See below for the full list of categories.

Other viewing options

View database as Thumbnail Gallery, reverse-chronological or chronological.

Techniques of Fakery

Numerous techniques of image manipulation are now available to photographers. Instead of trying to list every one, we've narrowed them down to a few broad categories.

Time Periods

Numerous techniques of image manipulation are now available to photographers. Instead of trying to list every one, we've narrowed them down to a few broad categories.

- Added Details

- Deleted Details

- False Caption

- Manipulating Existing Details

- Staged Scene

- Trick Angle

Time Periods

This page has been viewed 0 times.

Roosevelt Rides A Moose

Status:

Date: 1912

Date: 1912

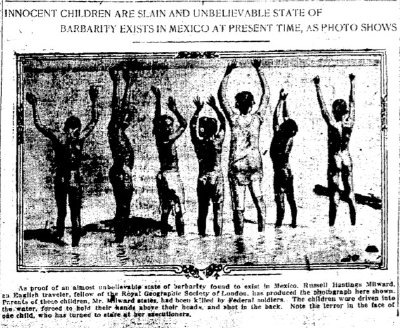

Ocean Execution

Status: False caption

Date: December 1913

Date: December 1913

Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst was notorious for allowing his newspapers to recaption photos creatively. In 1913 one of his papers, the New York American, ran a photo of children, their hands raised above their heads, standing in the ocean. Many other papers then reprinted the photo. The caption read:

The picture had not been altered, but the caption was entirely false. Milward protested that, in reality, the children had been playing happily, and that they had raised their arms at his request in order to make a better picture. What's more, the photo was taken in British Honduras, not Mexico.

As proof of an almost unbelievable state of barbarity found to exist in Mexico, Russell Hastings Milward, an English traveler, fellow of the Royal Geographic Society of London, has produced the photograph here shown. Parents of these children, Mr. Milward states, had been killed by Federal soldiers. The children were driven into the water, forced to hold their hands above their heads, and shot in the back. Note the terror in the face of one child, who has turned to stare at her executioners.

The picture had not been altered, but the caption was entirely false. Milward protested that, in reality, the children had been playing happily, and that they had raised their arms at his request in order to make a better picture. What's more, the photo was taken in British Honduras, not Mexico.

References:

December 27, 1913. The Lima Daily News.

MacDougall, C. (1958, 2nd ed.). Hoaxes. Dover Publications: 245.

December 27, 1913. The Lima Daily News.

MacDougall, C. (1958, 2nd ed.). Hoaxes. Dover Publications: 245.

The Cottingley Fairies

Status: Staged using paper cutouts

Date: 1917-1920

Date: 1917-1920

In 1920 a series of photos of fairies captured the attention of the world. The photos had been taken by two young girls, the cousins Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright, while playing in the garden of Elsie's Cottingley village home. Photographic experts examined the pictures and declared them genuine. Spiritualists promoted them as proof of the existence of supernatural creatures, and despite criticism by skeptics, the pictures became among the most widely recognized photos in the world. It was only decades later, in the late 1970s, that the photos were definitively debunked.

In July 1917 the pair asked to borrow the camera of Elsie's father, telling him they wanted to take a photo of the fairies they had been playing with all morning. Elsie's father laughingly agreed and showed them how to use the camera. An hour later the girls returned, declaring their project a success. And when Mr. Wright developed the plate that evening, he could see that there did indeed appear to be a fairy posing with Frances in the photo. However, he dismissed the girls' explanation, assuming the picture was some kind of trick. He asked Elsie why there appeared to be "bits of paper" in the photo.

Even when the girls took a second photo a little over a month later, showing Elsie with a gnome, the father treated the images as a joke and filed them away.

However, Elsie's mother, Polly Wright, had a stronger belief in the supernatural, and was more intrigued by the photos. In 1919 she attended a lecture on spiritualism and following it, she showed the photos to the speaker, asking him if they "might be true after all." The speaker brought the photos to the attention of Edward Gardner, a leader of the Theosophical movement, who in turn asked a photographer, Harold Snelling, to examine them. Snelling declared the photos were "genuine unfaked photographs of single exposure, open-air work, show movement in all the fairy figures, and there is no trace whatever of studio work involving card or paper models, dark backgrounds, painted figures, etc."

Once they had received this stamp of approval, the fairy images began circulating throughout the British spiritualist community, and soon came to the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries. Doyle was a passionate believer in spiritualism, and he latched onto the images, convinced they were conclusive photographic proof of the existence of supernatural fairy beings.

At Doyle's urging, the girls took three more pictures of fairies in August 1920. Doyle then wrote an article about the photographs that appeared in the December 1920 issue of The Strand Magazine, in which he passionately argued for the authenticity of the images. This article brought the photos to the attention of the wider public and sparked an international controversy that pitted spiritualists against skeptics.

#1. Frances and the Fairies. Taken July 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "The negative was a little over-exposed. The waterfall and rocks are about 20 feet distance behind Frances, who is standing in shallow water inside the bank of the beck. The colouring of the fairies was described by the girls as shades of green, lavender and mauve, most marked in the wings and fading to almost pure white in the limbs and drapery."

#1. Frances and the Fairies. Taken July 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "The negative was a little over-exposed. The waterfall and rocks are about 20 feet distance behind Frances, who is standing in shallow water inside the bank of the beck. The colouring of the fairies was described by the girls as shades of green, lavender and mauve, most marked in the wings and fading to almost pure white in the limbs and drapery."

#2. Elsie and the Gnome. Taken September 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "Elsie was playing with the gnome and beckoning it to come on to her knee. The gnome leapt up just as Frances, who had the camera, snapped the shutter. He is described as wearing black tights, a reddish jersey and a pointed bright red cap. Elsie said there was no perceptible weight, though when on the bare hand the feeling is like a 'little breath'. The wings were more moth-like than the fairies and of a soft neutral tint. Elsie explained that what seem to be markings on his wings are simply his pipes, which he was swinging in his grotesque little left hand."

#2. Elsie and the Gnome. Taken September 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "Elsie was playing with the gnome and beckoning it to come on to her knee. The gnome leapt up just as Frances, who had the camera, snapped the shutter. He is described as wearing black tights, a reddish jersey and a pointed bright red cap. Elsie said there was no perceptible weight, though when on the bare hand the feeling is like a 'little breath'. The wings were more moth-like than the fairies and of a soft neutral tint. Elsie explained that what seem to be markings on his wings are simply his pipes, which he was swinging in his grotesque little left hand."

#3. Frances and the Leaping Fairy. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is leaping up from the leaves below and hovering for a moment—it had done so three or four times. Rising a little higher than before, Frances thought it would touch her face, and involuntarily tossed her head back. The fairy's light covering appears to be close fitting: the wings were lavender in colour."

#3. Frances and the Leaping Fairy. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is leaping up from the leaves below and hovering for a moment—it had done so three or four times. Rising a little higher than before, Frances thought it would touch her face, and involuntarily tossed her head back. The fairy's light covering appears to be close fitting: the wings were lavender in colour."

#4. Fairy Offering a Posy to Elsie. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is standing almost still, poised on the bush leaves. The wings were shot with yellow. An interesting point is shown in this photograph: Elsie is not looking directly at the sprite. The reason seems to be that the human eye is disconcerting. If the fairy be actively moving it does not matter much, but if motionless and aware of being gazed at then the nature-spirit will usually withdraw and apparently vanish. With fairy lovers the habit of looking at first a little sideways is common."

#4. Fairy Offering a Posy to Elsie. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is standing almost still, poised on the bush leaves. The wings were shot with yellow. An interesting point is shown in this photograph: Elsie is not looking directly at the sprite. The reason seems to be that the human eye is disconcerting. If the fairy be actively moving it does not matter much, but if motionless and aware of being gazed at then the nature-spirit will usually withdraw and apparently vanish. With fairy lovers the habit of looking at first a little sideways is common."

#5. Fairies and Their Sun-Bath. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "This is especially remarkable as it contains a feature quite unknown to the girls. The sheath or cocoon appearing in the middle of the grasses had not been seen by them before, and they had no idea what it was. Fairy observers of Scotland and the New Forest, however, were familiar with it and described it as a magnetic bath, woven very quickly by the fairies and used after dull weather, in the autumn especially. The interior seems to be magnetised in some manner that stimulates and pleases."

#5. Fairies and Their Sun-Bath. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "This is especially remarkable as it contains a feature quite unknown to the girls. The sheath or cocoon appearing in the middle of the grasses had not been seen by them before, and they had no idea what it was. Fairy observers of Scotland and the New Forest, however, were familiar with it and described it as a magnetic bath, woven very quickly by the fairies and used after dull weather, in the autumn especially. The interior seems to be magnetised in some manner that stimulates and pleases."

Skeptics noticed many problems with the photos, in addition to the obvious one that the fairies look like bits of paper. For instance, in the first photo why is Frances not looking at the fairies? (The girls claimed they were so used to the fairies that they often paid them no attention.) And why does the second fairy from the left not have wings? In the second photo, why is Elsie's hand bizarrely elongated? (Frances attributed this to "camera slant.") In the fourth photo, why is the fairy dressed in the latest French fashions?

Despite these problems, the photos continued to attract believers. Much of this belief might be attributed to the context of the times. By the end of World War One the English were emotionally bruised and battered by four years of unrelenting bloodshed. They seemed to be in need of something that would reaffirm their belief in goodness and innocence. They found this reaffirmation in the fairy photographs of Frances and Elsie.

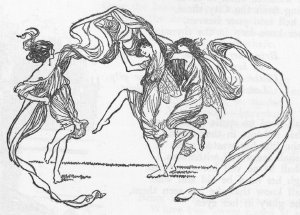

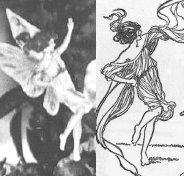

Fairy figures in Princess Mary's Gift BookIt was not until 1978 that James Randi pointed out that the fairies in the pictures were very similar to figures in a children's book called Princess Mary's Gift Book, which had been published in 1915 shortly before the girls took the photographs.

Subsequently, in 1981, Elsie Wright confessed to Joe Cooper, who interviewed her for The Unexplained magazine, that the fairies were, in fact, paper cutouts. She explained that she had sketched the fairies using Princess Mary's Gift Book as inspiration. She had then made paper cutouts from these sketches, which she held in place with hatpins. In the second photo (of Elsie and the gnome) the tip of a hatpin can actually be seen in the middle of the creature. Doyle had seen this dot, but interpreted it as the creature's belly button, leading him to argue that fairies give birth just like humans!

Below is a side-by-side comparison of the figures in Princess Mary's Gift Book and the fairies in the first Cottingley fairy photo.

The Museum of Hoaxes believes the Cottingley images to be in the public domain, and therefore did not remove the photos, nor has it agreed to pay a licensing fee for their use. The basis of our belief is that the images were published before 1923 in America. Specifically, they appeared in Arthur Conan Doyle's The Coming of the Fairies, published in 1922 by George H. Doran Co., New York. According to American law, all works published in this country before 1923 are in the public domain.

The status of the Cottingley images under British law is less clear cut, since British law grants continuing copyright to photographs taken before January 1, 1945 if the copyright has been revived. It is not clear whether or not the copyright to the Cottingley Fairy images was revived.

The possibly conflicting status of the Cottingley images under American and British law places them in an ambiguous legal situation. It is not clear which countries copyright law has priority. A possible precedent can be found in the case of J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, which is copyrighted in the UK, but is in the public domain in the US. Efforts to enforce the UK copyrights in America have been unsuccessful. When Project Gutenberg made the text of Peter Pan freely available on its site, it simply added a disclaimer noting that the text was public domain in the U.S., but not elsewhere.

Whether or not the Cottingley images are copyrighted, a strong case can be made that their use by sites such as the Museum of Hoaxes is protected by fair use laws — referred to as "fair dealing" laws in Great Britain — since they are displayed for the purpose of comment and criticism.

The Origin of the Photographs

During World War I, ten-year-old Frances Griffiths, who was from South Africa, moved into the English home of her aunt and uncle, the Wrights, while her father fought in the war. She and her cousin, thirteen-year-old Elsie, often played together in the large garden of the family's Cottingley village home.In July 1917 the pair asked to borrow the camera of Elsie's father, telling him they wanted to take a photo of the fairies they had been playing with all morning. Elsie's father laughingly agreed and showed them how to use the camera. An hour later the girls returned, declaring their project a success. And when Mr. Wright developed the plate that evening, he could see that there did indeed appear to be a fairy posing with Frances in the photo. However, he dismissed the girls' explanation, assuming the picture was some kind of trick. He asked Elsie why there appeared to be "bits of paper" in the photo.

Even when the girls took a second photo a little over a month later, showing Elsie with a gnome, the father treated the images as a joke and filed them away.

However, Elsie's mother, Polly Wright, had a stronger belief in the supernatural, and was more intrigued by the photos. In 1919 she attended a lecture on spiritualism and following it, she showed the photos to the speaker, asking him if they "might be true after all." The speaker brought the photos to the attention of Edward Gardner, a leader of the Theosophical movement, who in turn asked a photographer, Harold Snelling, to examine them. Snelling declared the photos were "genuine unfaked photographs of single exposure, open-air work, show movement in all the fairy figures, and there is no trace whatever of studio work involving card or paper models, dark backgrounds, painted figures, etc."

Once they had received this stamp of approval, the fairy images began circulating throughout the British spiritualist community, and soon came to the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries. Doyle was a passionate believer in spiritualism, and he latched onto the images, convinced they were conclusive photographic proof of the existence of supernatural fairy beings.

At Doyle's urging, the girls took three more pictures of fairies in August 1920. Doyle then wrote an article about the photographs that appeared in the December 1920 issue of The Strand Magazine, in which he passionately argued for the authenticity of the images. This article brought the photos to the attention of the wider public and sparked an international controversy that pitted spiritualists against skeptics.

The Photos

Shown below are the five Cottingley fairy photos, in the order in which they were taken. The text of the accompanying descriptions comes from Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs and Their Sequel by Edward Gardner (published 1945). #1. Frances and the Fairies. Taken July 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "The negative was a little over-exposed. The waterfall and rocks are about 20 feet distance behind Frances, who is standing in shallow water inside the bank of the beck. The colouring of the fairies was described by the girls as shades of green, lavender and mauve, most marked in the wings and fading to almost pure white in the limbs and drapery."

#1. Frances and the Fairies. Taken July 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "The negative was a little over-exposed. The waterfall and rocks are about 20 feet distance behind Frances, who is standing in shallow water inside the bank of the beck. The colouring of the fairies was described by the girls as shades of green, lavender and mauve, most marked in the wings and fading to almost pure white in the limbs and drapery." #2. Elsie and the Gnome. Taken September 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "Elsie was playing with the gnome and beckoning it to come on to her knee. The gnome leapt up just as Frances, who had the camera, snapped the shutter. He is described as wearing black tights, a reddish jersey and a pointed bright red cap. Elsie said there was no perceptible weight, though when on the bare hand the feeling is like a 'little breath'. The wings were more moth-like than the fairies and of a soft neutral tint. Elsie explained that what seem to be markings on his wings are simply his pipes, which he was swinging in his grotesque little left hand."

#2. Elsie and the Gnome. Taken September 1917. Camera: Midg Quarter. "Elsie was playing with the gnome and beckoning it to come on to her knee. The gnome leapt up just as Frances, who had the camera, snapped the shutter. He is described as wearing black tights, a reddish jersey and a pointed bright red cap. Elsie said there was no perceptible weight, though when on the bare hand the feeling is like a 'little breath'. The wings were more moth-like than the fairies and of a soft neutral tint. Elsie explained that what seem to be markings on his wings are simply his pipes, which he was swinging in his grotesque little left hand." #3. Frances and the Leaping Fairy. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is leaping up from the leaves below and hovering for a moment—it had done so three or four times. Rising a little higher than before, Frances thought it would touch her face, and involuntarily tossed her head back. The fairy's light covering appears to be close fitting: the wings were lavender in colour."

#3. Frances and the Leaping Fairy. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is leaping up from the leaves below and hovering for a moment—it had done so three or four times. Rising a little higher than before, Frances thought it would touch her face, and involuntarily tossed her head back. The fairy's light covering appears to be close fitting: the wings were lavender in colour."  #4. Fairy Offering a Posy to Elsie. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is standing almost still, poised on the bush leaves. The wings were shot with yellow. An interesting point is shown in this photograph: Elsie is not looking directly at the sprite. The reason seems to be that the human eye is disconcerting. If the fairy be actively moving it does not matter much, but if motionless and aware of being gazed at then the nature-spirit will usually withdraw and apparently vanish. With fairy lovers the habit of looking at first a little sideways is common."

#4. Fairy Offering a Posy to Elsie. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "The fairy is standing almost still, poised on the bush leaves. The wings were shot with yellow. An interesting point is shown in this photograph: Elsie is not looking directly at the sprite. The reason seems to be that the human eye is disconcerting. If the fairy be actively moving it does not matter much, but if motionless and aware of being gazed at then the nature-spirit will usually withdraw and apparently vanish. With fairy lovers the habit of looking at first a little sideways is common." #5. Fairies and Their Sun-Bath. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "This is especially remarkable as it contains a feature quite unknown to the girls. The sheath or cocoon appearing in the middle of the grasses had not been seen by them before, and they had no idea what it was. Fairy observers of Scotland and the New Forest, however, were familiar with it and described it as a magnetic bath, woven very quickly by the fairies and used after dull weather, in the autumn especially. The interior seems to be magnetised in some manner that stimulates and pleases."

#5. Fairies and Their Sun-Bath. Taken August 1920. Camera: Cameo Quarter. "This is especially remarkable as it contains a feature quite unknown to the girls. The sheath or cocoon appearing in the middle of the grasses had not been seen by them before, and they had no idea what it was. Fairy observers of Scotland and the New Forest, however, were familiar with it and described it as a magnetic bath, woven very quickly by the fairies and used after dull weather, in the autumn especially. The interior seems to be magnetised in some manner that stimulates and pleases."Controversy

Skeptics noticed many problems with the photos, in addition to the obvious one that the fairies look like bits of paper. For instance, in the first photo why is Frances not looking at the fairies? (The girls claimed they were so used to the fairies that they often paid them no attention.) And why does the second fairy from the left not have wings? In the second photo, why is Elsie's hand bizarrely elongated? (Frances attributed this to "camera slant.") In the fourth photo, why is the fairy dressed in the latest French fashions?

Despite these problems, the photos continued to attract believers. Much of this belief might be attributed to the context of the times. By the end of World War One the English were emotionally bruised and battered by four years of unrelenting bloodshed. They seemed to be in need of something that would reaffirm their belief in goodness and innocence. They found this reaffirmation in the fairy photographs of Frances and Elsie.

Debunked

Fairy figures in Princess Mary's Gift Book

Subsequently, in 1981, Elsie Wright confessed to Joe Cooper, who interviewed her for The Unexplained magazine, that the fairies were, in fact, paper cutouts. She explained that she had sketched the fairies using Princess Mary's Gift Book as inspiration. She had then made paper cutouts from these sketches, which she held in place with hatpins. In the second photo (of Elsie and the gnome) the tip of a hatpin can actually be seen in the middle of the creature. Doyle had seen this dot, but interpreted it as the creature's belly button, leading him to argue that fairies give birth just like humans!

Below is a side-by-side comparison of the figures in Princess Mary's Gift Book and the fairies in the first Cottingley fairy photo.

|  |  |

Copyright Controversy

The copyright status of the Cottingley fairy photos is contested. The Science and Society Picture Library, claiming to represent the photographers' estate, has asserted exclusive right to license the use of the images. In May 2005 it sent infringement notices to many sites (including the Museum of Hoaxes) that were displaying the photos. It demanded fees of up to 130.00 GBP per year for the right to display each image.The Museum of Hoaxes believes the Cottingley images to be in the public domain, and therefore did not remove the photos, nor has it agreed to pay a licensing fee for their use. The basis of our belief is that the images were published before 1923 in America. Specifically, they appeared in Arthur Conan Doyle's The Coming of the Fairies, published in 1922 by George H. Doran Co., New York. According to American law, all works published in this country before 1923 are in the public domain.

The status of the Cottingley images under British law is less clear cut, since British law grants continuing copyright to photographs taken before January 1, 1945 if the copyright has been revived. It is not clear whether or not the copyright to the Cottingley Fairy images was revived.

The possibly conflicting status of the Cottingley images under American and British law places them in an ambiguous legal situation. It is not clear which countries copyright law has priority. A possible precedent can be found in the case of J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan, which is copyrighted in the UK, but is in the public domain in the US. Efforts to enforce the UK copyrights in America have been unsuccessful. When Project Gutenberg made the text of Peter Pan freely available on its site, it simply added a disclaimer noting that the text was public domain in the U.S., but not elsewhere.

Whether or not the Cottingley images are copyrighted, a strong case can be made that their use by sites such as the Museum of Hoaxes is protected by fair use laws — referred to as "fair dealing" laws in Great Britain — since they are displayed for the purpose of comment and criticism.

References:

- Gardner, Edward L. (1951). Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs and Their Sequel. The Theosophical Publishing House London Ltd. Second Edition.

- The Cottingley Fairies, Cottingley.net

- The Case of the Cottingley Fairies, Joe Cooper.

Technique: Staged Scene, Models and Cutouts. Time Period: 1900-1919.

Themes: Children, Paranormal, Striking a Pose,.

Themes: Children, Paranormal, Striking a Pose,.

Trotsky Vanishes

|

|

Status: Fake (deleted person)

Date: Taken in 1919; altered ca. 1967

Date: Taken in 1919; altered ca. 1967

Leon Trotsky was a leader of the Russian October Revolution, second in command to Lenin. During the 1920s he opposed the policies of Stalin. As a consequence, he was deported and eventually assassinated.

When historian David King visited Moscow in 1970, he discovered that the Soviets had made a systematic attempt to purge all mention of Trotsky -- as well as any other person who had fallen out of political favor -- from historical records. This included removing Trotsky's image from photographs. King decided to start collecting examples of the Soviet falsification of photographs. In 1997 he published a book based on his collection, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia.

The top image, from King's collection, was taken by L.Y. Leonidov on November 7, 1919. It shows Soviet party leaders celebrating the second anniversary of the October Revolution in Red Square. Trotsky (wearing a hat and saluting) is standing near the center of the image to Lenin's left.

In 1967 a doctored version of the photo (bottom) was included in an exhibition in Moscow. Trotsky had disappeared from it. Also gone were L.B. Kamenev (who was to Lenin's immediate left) and A.B. Khalatov (the bearded man who was standing in front of the child and Trotsky).

When historian David King visited Moscow in 1970, he discovered that the Soviets had made a systematic attempt to purge all mention of Trotsky -- as well as any other person who had fallen out of political favor -- from historical records. This included removing Trotsky's image from photographs. King decided to start collecting examples of the Soviet falsification of photographs. In 1997 he published a book based on his collection, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia.

The top image, from King's collection, was taken by L.Y. Leonidov on November 7, 1919. It shows Soviet party leaders celebrating the second anniversary of the October Revolution in Red Square. Trotsky (wearing a hat and saluting) is standing near the center of the image to Lenin's left.

In 1967 a doctored version of the photo (bottom) was included in an exhibition in Moscow. Trotsky had disappeared from it. Also gone were L.B. Kamenev (who was to Lenin's immediate left) and A.B. Khalatov (the bearded man who was standing in front of the child and Trotsky).

References:

• King, David. (Dec 2000). "Photographic images should not be relied upon, but even falsified photographs can be illuminating for students of History." New Perspective. PDF File.

• King, David. (Dec 2000). "Photographic images should not be relied upon, but even falsified photographs can be illuminating for students of History." New Perspective. PDF File.

Stotham, Massachusetts: The Town That Didn’t Exist

Status: Real pictures, falsely captioned

Date: April 1920

Date: April 1920

The White Pine Monograph Series was a series of carefully researched, high quality brochures, paid for by Weyerhaeuser mills and edited by Russell Whitehead, that collected together photographs, drawings, and descriptions of early American buildings built with white pine. It was published bimonthly between 1915 and 1940, and sent to architects, with the goal of encouraging them to use white pine as a building material. The series was considered to be so expertly produced, that many architects preserved bound copies of the monographs in their offices. The series can still be found in many architectural libraries today.

Given its intended audience, the White Pine series was not the kind of publication that contained a lot of humor. However, it did include one unusual item. The April 1920 issue (vol. VI, No. 2) contained an article, written by Hubert G. Ripley, about the town of Stotham, Massachusetts. It contained many photographs of houses and buildings in the town.

Frontispiece of Hubert Ripley’s article

The article began by offering a short history of the town:

The building identified as the 'Meeting House of the Stotham Congregation Society (above) was, in reality, the North Congregational Church Parish House of Woodbury, Connecticut (below -- click to view on Google maps).

Ripley proceeded to paint a picture of Stotham as a village seemingly untouched by modernity, where ancient traditions were kept alive. He offered brief histories of some of the homes, such as the Rogers mansion, known locally as the "Haunted House." He also praised the townsfolk themselves:

Stotham, Ripley concluded, was a village "where the quintessence of naturalness finds its ultimate expression."

Holland's staff reported back to him that they had successfully cataloged everything in the series, but that they had encountered a problem when they came to the article about Stotham. Try as they might, they couldn't find any evidence of the town's existence, despite having pored over maps and histories of Massachusetts. Nor could they find references to any of the characters, such as Zabdiel Podbury, mentioned by Ripley in his article.

In reality, a house in Bedford, Massachusetts

Later Holland ran into Russell Whitehead, the former editor of the White Pine Series, and took the opportunity to ask his help in identifying the details of Stotham. John Harbeson, in an article that appeared in the May 1964 issue of The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, described what happened next.

In other words, although Stotham would have been a charming place to visit, it unfortunately didn't exist.

Given its intended audience, the White Pine series was not the kind of publication that contained a lot of humor. However, it did include one unusual item. The April 1920 issue (vol. VI, No. 2) contained an article, written by Hubert G. Ripley, about the town of Stotham, Massachusetts. It contained many photographs of houses and buildings in the town.

Frontispiece of Hubert Ripley’s article

The article began by offering a short history of the town:

When Zabdiel Podbury fled from Stoke-on-Tritham in the Spring of 1689 with Drusilla Ives, taking passage on the bark Promise, sailing for Massachusetts Bay, it was not realized at the time that, from this union, and the joint labors of the Penthesilean pair, the village of Stotham (so named by them in memory of their autochthonous abode) would in later days come to be regarded as a typical example, athough, perhaps, not so well known, of the unspoiled New England Village.

The building identified as the 'Meeting House of the Stotham Congregation Society (above) was, in reality, the North Congregational Church Parish House of Woodbury, Connecticut (below -- click to view on Google maps).

Ripley proceeded to paint a picture of Stotham as a village seemingly untouched by modernity, where ancient traditions were kept alive. He offered brief histories of some of the homes, such as the Rogers mansion, known locally as the "Haunted House." He also praised the townsfolk themselves:

It is the personal contact with the people themselves that lends an elusive charm to the externals of their environment. As the houses seem to show by their aspect, they are the personification, in their external and internal attributes, of the simplicity of life, and the friendly point of view, of the gentle folk who live in them.

Stotham, Ripley concluded, was a village "where the quintessence of naturalness finds its ultimate expression."

Questions Arise

For over two decades no one questioned Ripley's article about the idyllic town of Stotham. It was only when Leicester B. Holland, head of the Fine Arts Department of the Library of Congress, asked his staff to catalog all the material in the White Pine Series, that anyone realized something was amiss. Holland's staff reported back to him that they had successfully cataloged everything in the series, but that they had encountered a problem when they came to the article about Stotham. Try as they might, they couldn't find any evidence of the town's existence, despite having pored over maps and histories of Massachusetts. Nor could they find references to any of the characters, such as Zabdiel Podbury, mentioned by Ripley in his article.

In reality, a house in Bedford, Massachusetts

Later Holland ran into Russell Whitehead, the former editor of the White Pine Series, and took the opportunity to ask his help in identifying the details of Stotham. John Harbeson, in an article that appeared in the May 1964 issue of The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, described what happened next.

There was a short silence during which Whitehead maintained a completely expressionless face, and then a sly smile passed across it. Finally he told this story. As the early numbers had been assembled, about Quincy, the Boston Post Road, the Wooden Architecture of the Lower Delaware Valley, etc., the most appropriate photographs of whole buildings or of details were chosen for publication. Always a few were left over, as not being quite as good, or simply because there was not sufficient room. These were put in a big drawer. After a while the drawer was quite full. He and Hubert Ripley were looking through it one day; they were of the opinion many of the photographs were too good to be wasted, and they felt the public to which the White Pine Series was addressed was being deprived of some charming documents that would surely serve a purpose to the avid users of the data, many of them architects proud of their 'Early American' work. And so the plan was formed to create a village in which 'Zabdield Podbury who married Drusilla Ives, a Penthesilean pair named the village they founded Stotham, in memory of their autochthonous abode.'

In other words, although Stotham would have been a charming place to visit, it unfortunately didn't exist.

References:

- Harbeson, J.F. (May, 1964). "Stotham, The Massachusetts Hoax, 1920." The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 23(2): 111-112.

- Magruder, C. (March, 1963). "The White Pine Monograph Series." The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 22(1): 39-41.

- Ripley, H.G. (April, 1920). "A New England Village." The White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs. 6(2): 1-14.

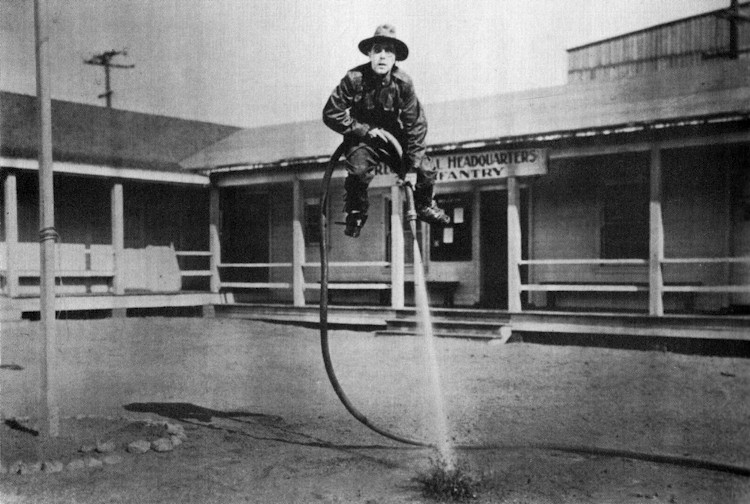

High-Pressure Hijinks

Status: Undetermined

Date: ca. 1923

Date: ca. 1923

A soldier appears to be lifted in the air by the pressure from a water hose.

Mark Sloan, in his book Hoaxes, Humbugs, and Spectacles (1990), dates this image to circa 1923. He credits it to "The New York Times; courtesy National Archives and Wide World Photos."

It's very unlikely the soldier actually was lifted in the air by the pressure from the hose. For a start, the blast from the hose is not directed at his center of gravity. Therefore, it would not be pushing him upwards.

Some have noted that the soldier resembles Buster Keaton. If it is Keaton, then this may be a scene from a movie, in which case the effect most likely was created with hidden wires.

Another possibility is that an image of a man with a hose was cut from another picture (perhaps of him sitting on top of a wall) and inserted into the background scene of the infantry headquarters.

Although the picture was obviously intended as a joke, its status is listed as undetermined since it isn't clear what technique was used to create it.

References:

Sloan, M. (1990). Hoaxes, Humbugs, and Spectacles. Villard Books: p.114.

Sloan, M. (1990). Hoaxes, Humbugs, and Spectacles. Villard Books: p.114.

Ada Emma Deane’s Armistice Day Series

Status: Fake (superimposed "spirit" faces)

Date: November 1924

Date: November 1924

Ada Emma Deane spent most of her life working as a cleaning lady before launching a new career as a photographic medium at the age of 58. She quickly became one of the most famous mediums in Britain. Her signature effect was that eerie, disembodied heads would appear in pictures taken by her. These heads, so it was claimed, were the manifestation of departed spirits. Skeptics pointed out that in order to produce this effect, Deane required that photographic plates be submitted to her in advance so that she could "pre-magnetise" them with her psychic powers. This gave her ample opportunity to tamper with the plates. But her defenders (who included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) insisted that no trickery was involved. They often argued that she was merely a simple cleaning lady who lacked the expertise to pull off such deception.

Deane's most famous photos were those she took, with the help of spiritualist Estelle Stead, during the two minutes silence at services commemorating Armistice Day and the end of World War I. In these photos ghostly figures and faces — supposedly the spirits of dead war heroes — could be seen floating above the crowd. She took the first such picture in 1921, and then again in 1922 (top) and 1923 (second from top). By 1924 her Armistice Day photo was highly anticipated, and newspapers bid on the rights to it. The Daily Sketch won the rights and published the resulting photo (second from bottom) on November 13, 1924. The photo showed a group of faces floating in a cloud above the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

But two days later The Daily Sketch announced it had discovered the photo to be a fraud. The faces in the cloud were not dead war heroes. Instead, they appeared to be living football players and boxers, including Battling Siki and Jimmy Wilde. The paper published portraits of the athletes alongside Deane's spirit photo (bottom). It denounced Deane as a "charlatan" who had perpetrated "a cruel fraud designed to deceive credulous people and bereaved relatives of the glorious dead."

Deane's defenders argued that they failed to see the similarity to the athletes — that, in fact, the faces were too blurry to positively identify. Deane herself said, "If I had wanted to produce a fraudulent photograph, is it likely I would have used portraits of well-known footballers or boxers?" Nevertheless, the incident put a serious dent in her reputation. She continued to work as a photographic medium for a number of years, but she never again took an Armistice Day photo.

Deane's most famous photos were those she took, with the help of spiritualist Estelle Stead, during the two minutes silence at services commemorating Armistice Day and the end of World War I. In these photos ghostly figures and faces — supposedly the spirits of dead war heroes — could be seen floating above the crowd. She took the first such picture in 1921, and then again in 1922 (top) and 1923 (second from top). By 1924 her Armistice Day photo was highly anticipated, and newspapers bid on the rights to it. The Daily Sketch won the rights and published the resulting photo (second from bottom) on November 13, 1924. The photo showed a group of faces floating in a cloud above the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

But two days later The Daily Sketch announced it had discovered the photo to be a fraud. The faces in the cloud were not dead war heroes. Instead, they appeared to be living football players and boxers, including Battling Siki and Jimmy Wilde. The paper published portraits of the athletes alongside Deane's spirit photo (bottom). It denounced Deane as a "charlatan" who had perpetrated "a cruel fraud designed to deceive credulous people and bereaved relatives of the glorious dead."

Deane's defenders argued that they failed to see the similarity to the athletes — that, in fact, the faces were too blurry to positively identify. Deane herself said, "If I had wanted to produce a fraudulent photograph, is it likely I would have used portraits of well-known footballers or boxers?" Nevertheless, the incident put a serious dent in her reputation. She continued to work as a photographic medium for a number of years, but she never again took an Armistice Day photo.

References:

• Fischer, Andreas. "The Most Disreputable Camera in the World: Spirit photography in the United Kingdom in the early twentieth century." in The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult. Yale University Press. 2004.

• Jolly, M.T. (2003). Fake Photographs: Making Truths in Photography. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Sydney. [PDF]

• Cloud with spirit faces. Flickr.

• Mrs. Ada Emma Deane's Ghost Picture. Columbia.edu.

• Fischer, Andreas. "The Most Disreputable Camera in the World: Spirit photography in the United Kingdom in the early twentieth century." in The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult. Yale University Press. 2004.

• Jolly, M.T. (2003). Fake Photographs: Making Truths in Photography. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Sydney. [PDF]

• Cloud with spirit faces. Flickr.

• Mrs. Ada Emma Deane's Ghost Picture. Columbia.edu.

Technique: Superimposed Image. Time Period: 1920-1939.

Themes: Death, Military, Paranormal, Ghosts,.

Themes: Death, Military, Paranormal, Ghosts,.

Bloody Sunday, 1905

Status: Staged reenactment

Date: 1925

Date: 1925

On January 22, 1905 (January 9 in the Old Style calendar) workers in St. Petersburg marched toward the Winter Palace intending to hand a petition to Tsar Nicholas II. Soldiers stopped them at the Narva Gate and opened fire. In Russia the day came to be known as Bloody Sunday. The event exposed the brutality of the Russian police and undermined popular support for the Tsarist regime.

In 1925 director Vyacheslav Viskovsky made a propaganda film about Bloody Sunday titled Devyatoe Yanvarya (January 9). The film included a reenactment of the soldiers firing on the crowd. This image shows the reenactment. (It is not clear whether it is a retouched still from the film itself, or a photograph that was taken during the filming.)

The image was more dramatic than any existing photographs of the Bloody Sunday massacre, and was soon distributed by the Soviet Tass News agency, which described it as an actual photograph of the 1905 event. Later it appeared in numerous Soviet textbooks, again presented as a photograph of the event itself, not as a staged reenactment.

In 1925 director Vyacheslav Viskovsky made a propaganda film about Bloody Sunday titled Devyatoe Yanvarya (January 9). The film included a reenactment of the soldiers firing on the crowd. This image shows the reenactment. (It is not clear whether it is a retouched still from the film itself, or a photograph that was taken during the filming.)

The image was more dramatic than any existing photographs of the Bloody Sunday massacre, and was soon distributed by the Soviet Tass News agency, which described it as an actual photograph of the 1905 event. Later it appeared in numerous Soviet textbooks, again presented as a photograph of the event itself, not as a staged reenactment.

References:

• Alain Jaubert. (1989). Making People Disappear: An amazing chronicle of photographic deception.

• Alain Jaubert. (1989). Making People Disappear: An amazing chronicle of photographic deception.

Mother Cat Stops Traffic

Status: Staged Scene

Date: July 29, 1925

Date: July 29, 1925

Harry Warnecke, a photographer for the New York News, got a phone tip about a cat trying to carry its kittens home who was tying up traffic because a policeman had stopped the cars on a busy street to allow it to cross. Warnecke arrived after the event was over, but he convinced the policeman and cat's owner to allow him to recreate the scene. Despite the policeman's initial reluctance, the cat's inclination to cross the street diagonally instead of in front of the cars, and furious honking motorists, Warnecke finally got his shot -- after three attempts.

References:

Faber, J. (1978, 2nd ed.). Great News Photos and the Stories Behind Them. Dover Publications: pgs 38-39.

Faber, J. (1978, 2nd ed.). Great News Photos and the Stories Behind Them. Dover Publications: pgs 38-39.

Technique: Staged Scene. Time Period: 1920-1939.

Themes: Animals, Cats, On the Road, Photojournalism,.

Themes: Animals, Cats, On the Road, Photojournalism,.

Death in the Air

Status: Staged with models

Date: Published in 1933; debunked in 1984.

Date: Published in 1933; debunked in 1984.

Death in the Air: The War Diary and Photographs of a Flying Corps Pilot, published in 1933, purported to be the diary of an anonymous World War I RAF pilot killed in combat. The manuscript, which included numerous spectacular shots of aerial combat, was presented to the publisher by a Mrs. Gladys Cockburn-Lange, who claimed to be the widow of a British pilot.

The photos attracted enormous interest, since there were very few images of World War I aerial combat in existence. However, many people were skeptical. Why was the name of the pilot not revealed? How could the RAF have had no knowledge of these photos? And how could such clear shots have been taken with a camera mounted on an airplane (given the state of camera technology during WWI)?

The photos weren't definitively debunked until 1984 when archivists at the Smithsonian realized that "Mrs. Gladys Cockburn-Lange" was actually Betty Archer, the wife of Wesley David Archer, a model maker in the film industry. Archer had created models of all the aircraft, and then had superimposed images of the planes onto aerial backgrounds.

"His wings suddenly collapsed and floated past me"

"Just as he left the burning plane"

"....family group as 'twere"

The photos attracted enormous interest, since there were very few images of World War I aerial combat in existence. However, many people were skeptical. Why was the name of the pilot not revealed? How could the RAF have had no knowledge of these photos? And how could such clear shots have been taken with a camera mounted on an airplane (given the state of camera technology during WWI)?

The photos weren't definitively debunked until 1984 when archivists at the Smithsonian realized that "Mrs. Gladys Cockburn-Lange" was actually Betty Archer, the wife of Wesley David Archer, a model maker in the film industry. Archer had created models of all the aircraft, and then had superimposed images of the planes onto aerial backgrounds.

The Photos

Below are examples of three of the faked photographs, along with the captions that accompanied them in Death in the Air.

"His wings suddenly collapsed and floated past me"

"Just as he left the burning plane"

"....family group as 'twere"

References:

Brugioni, D. (1999). Photo Fakery. Brassey's: 100-102.

Park, E. (Jan 1985). "The Greatest Aerial Warfare Photos Go Down in Flames." Smithsonian: 103-113.

Brugioni, D. (1999). Photo Fakery. Brassey's: 100-102.

Park, E. (Jan 1985). "The Greatest Aerial Warfare Photos Go Down in Flames." Smithsonian: 103-113.

Technique: Staged Scene, Models and Cutouts. Time Period: 1920-1939.

Themes: Death, Military, War, Planes,.

Themes: Death, Military, War, Planes,.