In 1935 veterans of World War One lobbied Congress to pay them their war bonuses ten years early in order to ease the economic hardship they were experiencing during the Great Depression. Congress readily acquiesced and passed the Harrison Bonus Bill in January 1936.

This pre-payment was a source of inspiration for Lewis Gorin, a senior at Princeton University. It seemed logical to him that if present-day veterans could get their war bonuses early, why shouldn't

future veterans also receive their money up-front — before they had fought in a war. After all, given the global political situation, it seemed inevitable to Gorin that all the young men in the country would soon have to go off to fight. Why shouldn't these future veterans be given their money now, while they could still enjoy it, instead of having to wait until after the conflict, when they might be dead?

The Veterans of Future Wars is Formed

While attending a tea party at the Terrace Club in March 1936, Gorin shared his idea with his friend, Thomas Riggs Jr. Immediately the two of them decided to found an organization to promote the cause of future veterans. Thus the Veterans of Future Wars was born. A few days later the manifesto of their organization appeared in the

Daily Princetonian. It read:

Whereas it is inevitable that this country will be engaged in war within the next thirty years, and whereas it is by all accounts likely that every man of military age will have a part in this war,

We, therefore, demand that the Government make known its intention to pay an adjusted service compensation, sometimes called a bonus, of $1,000 to every male citizen between the ages of 18 and 36, said bonus to be payable the first of June, 1965. Furthermore, we believe a study of history demonstrates that it is customary to pay all bonuses before they are due. Therefore we demand immediate cash payment, plus three per cent interest compounded annually and retroactively from the first of June, 1965, to the first of June, 1935. It is but common right that this bonus be paid now, for many will be killed or wounded in the next war, and hence they, the most deserving, will not otherwise get the full benefit of their country's gratitude.

The Movement Spreads

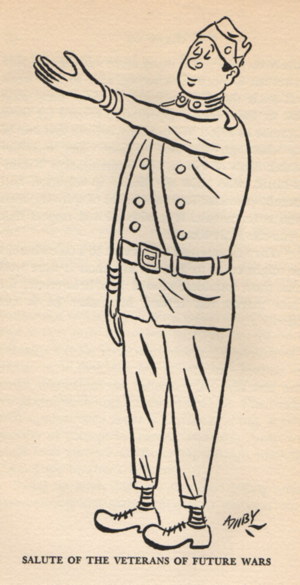

Wire services picked up the manifesto, spread it nationwide, and soon local chapters of the Veterans of Future Wars began popping up at campuses throughout the nation. Enthusiastic new members from as far away as North Dakota paid dues to the main chapter in Princeton and adopted the organization's salute: arm held out towards Washington with "hand outstretched, palm up and expectant" (a mockery of the fascist salute then gaining currency in Europe). At its peak, in June 1936, the Veterans of Future Wars had over 50,000 paid-up members.

Spin-offs of the organization began to appear. The women of Vassar College started an auxiliary called the "Association of Gold Star Mothers of Future Veterans" (after the Gold Star Mothers) and demanded that Congress send them to France to view "the future burying ground of our dead" (the real Gold Star Mothers had been sent to France to view the graves of their sons). But in the face of withering public outcry (how could anyone make fun of the Gold Star Mothers?) the women of Vassar lost their nerve and changed the name of their organization to the much tamer "Home Fire Division."

'Commander' Gorin on the steps of Nassau Hall, Princeton

giving a pep talk to members of the Veterans of Future Wars

The students of Rensselaer Polytechnic formed the "Future Profiteers of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute" and demanded that the military pay them early for war contracts they would complete in the future. At Rutgers the "Association of Future War Propagandists" appeared, while at City College of New York the "Foreign Correspondents of Future Wars" requested "training courses for members of the association in the writing of atrocity stories and garbled war dispatches for patriotic purposes." Probably the most forthright spin-off of all was the "Future Gold Diggers of Sweetbriar College."

What was the message?

A Regional Commander salutes his fellow future veterans, "hand outstretched, palm up and expectant"

In its original formulation, the Veterans of Future Wars was as much about satirizing government largesse as it was about lampooning the sabre-rattling of those urging war with Germany. But as it spread nationwide, the anti-war side of the concept quickly came to dominate.

One correspondent to

Time Magazine articulated the anti-war appeal of the Veterans of Future Wars in this way: "It's a 20th Century 'Don Quixote' packed with the dynamite of 'war babies' turning the guns of ridicule on the goose-stepping, gun-toting generation which splashed through the biggest blood-bath in history — and emerged crying for more" (

Time, April 6, 1936).

The Chicago University chapter of the V.F.W. came up with the slogan: "We'll make the world safe for hypocrisy" (mocking the phrase, "making the world safe for democracy.") And during one parade, V.F.W.'s carried death's-heads and crutches.

Future veterans march in New York down Broadway, past Columbia University

Controversy

Many real veterans disliked the movement. National Commander James E. Van Zandt of the Veterans of Foreign Wars sneered, "They're too yellow to go to war... They'll never be veterans of a future war." Representative Fuller of Arkansas got up in Congress to declare that "Such organizations are unworthy of public notice and should be denounced by every true American." Maj. Gen. Amos A. Fries, retired, denounced it as "just a damned fool idea."

However, there were also some voices of support from those in power. Eleanor Roosevelt said, "I think it's just as funny as it can be! And -- taken light, as it should be -- a grand pricking of lots of bubbles." Though she also cautioned that, if it were taken too far, it might "hurt some feelings."

The End of the Movement

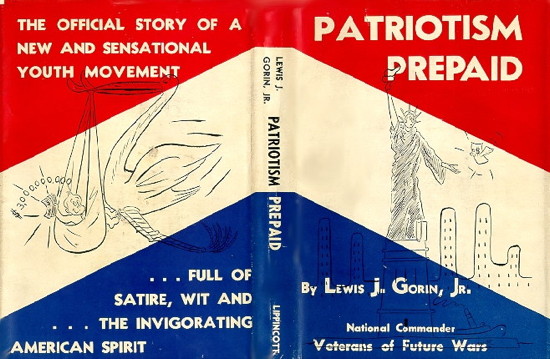

The movement continued on throughout 1936, with Gorin publishing a book,

Patriotism Prepaid, in which he elaborated on the VFW concept. However, by 1937 the joke had run its course, and the 584 nationwide chapters of the Veterans of Future Wars began to disband. The movement officially ended in April, 1937. The officers wrote an "obituary" of the organization, stating they had achieved their objectives by awakening the country to "the absurdity of war" and to the "equal absurdity of the Treasury exploitation in which the various veterans organizations had been allowed to indulge."

There was a brief effort to revive the movement in 1950 at the start of the Korean War, but by then the joke had lost its freshness and went nowhere.

In 2003 an online version of the organization appeared, with a website at

vofw.org. The authors of this website claimed that the new organization represented all those soldiers who would, in the future, fight wars in the following countries scheduled to be invaded: Afghanistan (2002), Iraq (2003), North Korea (2004), Iran (2005), Libya (2006), Somalia (2007), Syria (2008), Yemen (2009), Indonesia (2010), China (2011), Japan (2012), Germany (2013), France (2013), Australia (2014), Mexico (2015), Canada (2016), and California (2017).

True To Its Name

In the most fitting rebuke to those who had questioned their patriotism, all of the original Princeton members of the Veterans of Future Wars, except two, served in World War Two. Of the two who did not serve, one was injured in an automobile accident, and the other worked in an essential industry (steel). The two founders of the VFW, Gorin and Riggs, both served abroad.

Links and References

- Lewis J. Gorin, Jr. (1936). Patriotism Prepaid. J.B. Lippincott Company.

- "Future Veterans". Time. March 30, 1936: 38.

- "Future Veterans Amuse First Lady." (April 3, 1936). The Washington Post.

- "As Time Goes By." (July 26, 1943). Time Magazine.

Comments