The Vegetable Lamb, an example of a Lusus Naturae

Medieval naturalists had a great appreciation of hoaxes, and they spent a lot of time collecting and studying them. However, they didn't call them hoaxes. Instead, they called them

Lusus Naturae, or Jokes of Nature.

The term

Lusus Naturae described any creature or specimen that defied classification. One famous example was the Scythian Lamb, or Vegetable Lamb. This bizarre creature, which medieval naturalists were sure existed, although they couldn't locate a specimen, was part plant and part animal. It consisted of a lamb from whose belly grew a thick stem that was firmly rooted in the ground. Thus rendered immobile, the creature survived by eating the grass which grew around it. Medieval naturalists labelled the creature a

Lusus Naturae because it defied classification, being neither plant nor animal.

The category of

Lusus Naturae was not simply a way for medieval naturalists to avoid classifying puzzling creatures. It actually symbolized a belief that Nature was an active, sentient force that enjoyed playing jokes on man, that enjoyed confounding his expectations and subverting his classification schemes. In other words, medieval naturalists believed that Nature was the greatest hoaxer of all.

The category of

Lusus Naturae included inanimate as well as animate objects. The naturalist Athanasius Kircher kept a collection of objects in which he had discovered the shapes of crosses. He believed that Nature had purposefully placed the crosses in the objects as a kind of game, intending for him to find them. The seventeenth century Veronese collector Lodovico Moscardo greatly prized a stone in which he discerned the shapes of trees, houses, and countrysides. He thought it was an example of Nature parodying human art by creating an image in a stone similar to something a man might draw.

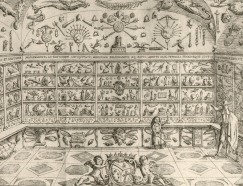

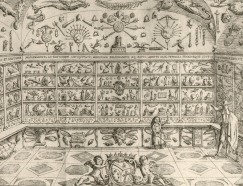

The Museum of Marchese Ferdinando Cospi.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the growing interest in the study of nature prompted the establishment of the first museums in Europe. They appeared first in Italy, but soon spread to the rest of the continent. These early museums were, to use the phrase of the historian Paula Findlen, like 'repositories of wonders,' full of bizarre natural specimens: fossils, birds, bones, monstrosities, and

Lusus Naturae. Remains of legendary creatures such as the unicorn rested alongside examples of more mundane creatures. The curators of these museums also created elaborate jokes of their own designed to mimic nature's capacity for joking: optical illusion shows involving magic lanterns and distorting mirrors, or levitation tricks that used magnets and string. Because these museums gathered together the jokes of nature and the jokes of man, they can be considered to be the original Museums of Hoaxes.

By the end of the seventeenth century the concept of

Lusus Naturae was disappearing. In its place emerged the modern scientific view that nature does not joke, that nature follows strict rules and laws which men can learn and manipulate.

Lusus Naturae exhibits were eventually relocated from museums to circus sideshows, but wherever they were displayed, they continued to fascinate audiences with their category-defying mystery.

Links and References

- Paula Findlen. "Jokes of Nature and Jokes of Knowledge: The Playfulness of Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Europe." Renaissance Quarterly 43 (1990): 292-331.

- Paula Findlen. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Comments

~Joel