In 1983, the novel

The Diary of a Good Neighbor was published in Great Britain and the United States. It told the story of a successful middle-aged magazine editor who befriends a lonely old woman. The cover identified the author as Jane Somers, a name that was said to be the pseudonym of a "well-known English woman journalist." The book received little critical attention, and had only modest sales. Approximately 1500 copies sold in the UK and 3000 in the United States.

A year later a sequel appeared,

If the Old Could. But a surprise announcement accompanied its publication. Doris Lessing revealed herself to be the author of both works. Lessing, of course, is a major literary figure. Even at that time, in her early sixties, she was considered to be a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. (She won the prize in 2007.) Her novel

Golden Notebook, published in 1962, had sold more than 900,000 copies, and her series of five novels,

The Children of Violence, had sold almost a million copies. Why had she concealed her authorship of

The Diary of a Good Neighbor?

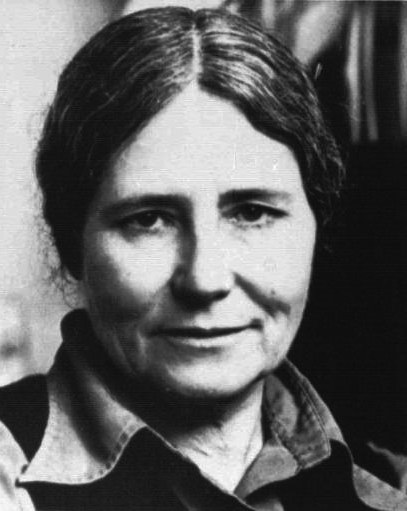

Doris Lessing in 1982

Motive

Lessing explained her intentions in a preface to a one-volume edition of both works. She said she wanted to illustrate how difficult it is for unknown authors to attract attention. Also, she wanted to play a prank on critics who insisted on pigeonholing her as one type of writer or another.

"I wanted to be reviewed on merit, as a new writer, without the benefit of a 'name,' to get free of that cage of associations and labels that every established writer has to learn to live inside."

"The reviews were more or less what I expected. It was interesting to be a beginning writer again because I found how patronizing reviewers can be. I was compared to Barbara Pym. That made me laugh. You are patted on the head and found promising."

Lessing also wanted to expose how difficult it is for unknown writers to get published -- particularly how publishers can be influenced by the name attached to a book as much as by the work itself.

As Doris Lessing it was easy for her to get a book published. But as Jane Somers, it was much more difficult. Lessing's two main London publishers (not realizing she was the true author of the work) both turned down

The Diary of a Good Neighbor. Jonathan Cape, the publisher of many of her works, said it was pretty good, but not commercially viable. Granada said it was "too depressing." Eventually it was accepted by Michael Joseph, who was then let in on the secret and agreed to go along with the experiment. Only Robert Gottlieb, Lessing's New York publisher, immediately recognized that Lessing was the true author of the work.

Controversy

Jonathan Yardley, writing in the

Washington Post, accused Lessing of having contradictory motives for her hoax, and dismissed what she had done as little more than a publicity stunt.

Lessing claimed that she wanted to demonstrate how in book publishing "nothing succeeds like success," but she also wanted to be reviewed honestly since "if the books had come out in my name, they would have sold a lot of copies and reviewers would have said, 'Oh, Doris Lessing, how wonderful.'" Yardley noted:

There's an obvious contradiction here. If Lessing's first point about famous authors is correct, then it stands to reason that when reviewers saw the "Canopus" novels with her name on them they would have said, "Oh, Doris Lessing, how wonderful" and given them favorable notices regardless of their actual merit. But that did not happen. Instead, after reading the novels a great many reviewers said, in effect, "Oh, Doris Lessing, how terrible." One can't help but wonder: Is it the success syndrome that really bothers Lessing, or is it that reviewers refused to be seduced by her name on the "Canopus" novels and picked them to pieces?

Certainly a success syndrome exists in the book industry, and reviewers are susceptible to it as well as publishers. But it also exists in the minds of writers, an aspect of the situation that is conveniently ignored in Lessing's argument. If it is true that famous authors too often get free rides from publishers and critics, then it is equally true that famous authors expect free rides. The ego of an author can be a monumental thing -- especially, need it be said, that of a famous one -- and it can lead the author to believe that everything he or she writes is a work of genius. This, as it happens, is not always true, but one constant remains: Famous authors expect all their books to be published, to be praised and to sell...

If anything, the Lessing case proves that the unknown but serious writer stands a reasonable chance of getting review attention, if not vast sales. The Jane Somers novels were reviewed by all three major American newspaper book-review supplements, which hardly justifies her complaint that "there were almost no reviews." The editors of those supplements obviously were able to spot the work of the unknown Jane Somers on their shelves, to recognize that it deserved a thoughtful reading, and to assign it for review. Jane Somers got pretty much the same treatment as any unknown novelist receives, and that treatment is neither as unfair nor as indifferent as Lessing imagines it to be. Her contention that book-review editors spend insufficient time looking for good books, regardless of the identity of their authors, is simply without foundation; the search for good but undiscovered books is what keeps many people in a business that too often presents them only with bad or mediocre ones...

What would have happened had Doris Lessing kept on writing as Jane Somers? Rather than spill the beans all over the newspapers and television, what if Lessing had given real weight to her experiment by carrying it to the end? To publish two pseudonymous novels and then almost immediately declare one's authorship is no genuine test of anything except the public's appetite for literary tempests; but to have kept plugging away as Jane Somers, that would have been a real test...

That Lessing chose not to follow this course is understandable and she deserves no criticism for failing to do so. But with a paperback edition of the two novels under the title "The Diaries of Jane Somers" now about to appear, bearing Lessing's name on the cover and including a new introduction by her, the sight of Lessing chasing after newspaper reporters and television interviewers to leak her story is something less than becoming. Were it not for her unsullied reputation for high solemnity and ideological rectitude, it would look for all the world as if the woman were staging a publicity stunt.

Links and References

- McDowell, Edwin. (September 23, 1984). "Doris Lessing says she used pen name to show new writers' difficulties." The New York Times.

- Yardley, Jonathan. (October 1, 1984). "Lessing is more: An 'unknown' author and the success syndrome." The Washington Post.

Comments