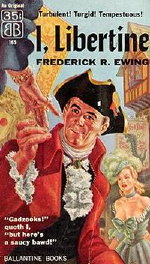

On September 20, 1956 Ballantine Books published

I, Libertine, a novel by Frederick R. Ewing. It was advertised as a "turbulent, turgid, tempestuous" tale of eighteenth-century court life in London. However, Ewing didn't actually exist. Both he and the book were the creation of nighttime deejay Jean Shepherd, devised as an elaborate hoax upon "day people."

The Night People

When Jean Shepherd started out as a deejay at WOR in New York City in the early 1950s, the only timeslot he could get was from 12-5 in the morning, the graveyard shift. But Shepherd didn't mind. In fact, he liked it because it gave him the freedom to experiment with the concept of radio entertainment. Alone in the studio at night, he threw out the scripted, highly packaged format that had been the norm up until that time, and began talking off the top of his head, delivering dark, comedic monologues about whatever was on his mind that day.

Soon he had developed a devoted following. People called in with comments of their own. His listeners enjoyed a sense of belonging to a secret, close-knit community that existed on the margins of normal society. Shepherd called his listeners the "night people." They even had their own password, "Excelsior," with which they could identify each other out in public. The appropriate response was "seltzer bottle."

Shepherd frequently mused on the difference between night people and day people. Night people, he said, were more creative because "night is the time people truly become individuals because all the familiar things are dark and done; all the restrictions on freedom are removed."

Day people, on the other hand, were bound by rules, lists, and schedules. They were, he said, the victims of "creeping meatballism," and the inventors of red tape.

Origin of I, Libertine

One day in April 1955, Shepherd walked into a Doubleday Book Shop on Fifth Avenue and asked the clerk if the store carried the script of the old radio serial "Vic and Sade." The clerk consulted a list of published books and told Shepherd that not only did they not have it, but that the book didn't exist. Shepherd insisted the book did exist. He was sure of it. But the clerk insisted it didn't because it wasn't on the list.

The incident enraged Shepherd. He felt it epitomized the difference between day people and night people because the bookstore clerk, evidently a day person, couldn't imagine a book might exist if it wasn't on his list of published books.

As Shepherd later shared these thoughts with his listeners, a practical joke occurred to him. All the night people, he suggested, should descend on bookstores, en masse, and request a book that truly didn't exist. The day people would be driven mad searching for this non-existent book. It would shake their faith in their lists.

Shepherd's listeners embraced his plan with a passion. One of them came up with a name for the fake novel:

I, Libertine. Someone else suggested it should be written by an expert on eighteenth-century erotica, and someone else came up with a name for this expert: Frederick R. Ewing.

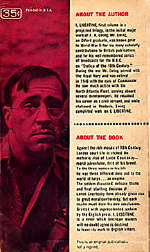

As the conversation continued, an entire biography was invented for Ewing. He was to have been an Oxford graduate, a retired Royal Navy Commander and a scholar "well remembered" for his series of BBC talks on "Erotica of the 18th century."

Perpetrating the Hoax

On the day after Shepherd first proposed the idea, 27 requests were placed at the 5th Avenue Bookstore for

I, Libertine. And in the following weeks, Shepherd's fans made their way to bookstores throughout the United States to order the book. One of his listeners, a steward on the Queen Mary, even placed requests for it at stores in England and in Scandinavia.

Some listeners created fake library cards and snuck them into the card catalogs at libraries. A student at Tufts was said to have turned in a book report about

I, Libertine. His professor, who also happened to be a fan of Shepherd, gave it a B+ and wrote "Excelsior!" on the bottom.

The Hoax Becomes Real

Puzzled bookstore owners didn't know what to make of the multiple requests for

I, Libertine. They contacted publishers, to inquire when this novel that everyone was talking about would be released. And in this way, word of the book eventually made its way to the publisher Ian Ballantine, who traced it back to Shepherd.

Ballantine thought it would be an interesting idea to capitalize on the hoax by publishing the book for real. Shepherd agreed to the idea, and science-fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon, who was also a fan of Shepherd, was commissioned to write the text.

Sturgeon wrote the novel in 30 days, and it was released on September 20, 1956 with a print run of 130,000 copies. Shepherd posed as Frederick Ewing for the author photo on the back cover. In a postscript, special thanks were given to the night people, "whose battle cry is Excelsior, and whose humor and forbearance are really responsible for the work."

The hoax had been revealed a month before the publication date, and the resulting publicity helped sales, even though reviews of the novel itself were generally lukewarm. One reviewer wrote, "Despite a couple of ingenious twists, there is one spot where the novel almost comes to a halt, and the loving is pretty sleazy." Another said, "Throughout, the characters are depicted in a manner that suggests, at time, that they might have descended not from English nobility but contemporary spacemen." Copies of the book are now considered collector's items and can fetch hundreds of dollars.

Links and References

- Henderson, Carter. (Aug 1, 1956). "Night people's hoax on day people makes hit with book folks." The Wall Street Journal.

- Brazda, Jerome. (Aug 2, 1956). "Day Time Squares Hoaxed." Oxford Press-Courier.

When Jean Shepherd started out as a deejay at WOR in New York City in the early 1950s, the only timeslot he could get was from 12-5 in the morning, the graveyard shift. But Shepherd didn't mind. In fact, he liked it because it gave him the freedom to experiment with the concept of radio entertainment. Alone in the studio at night, he threw out the scripted, highly packaged format that had been the norm up until that time, and began talking off the top of his head, delivering dark, comedic monologues about whatever was on his mind that day.

When Jean Shepherd started out as a deejay at WOR in New York City in the early 1950s, the only timeslot he could get was from 12-5 in the morning, the graveyard shift. But Shepherd didn't mind. In fact, he liked it because it gave him the freedom to experiment with the concept of radio entertainment. Alone in the studio at night, he threw out the scripted, highly packaged format that had been the norm up until that time, and began talking off the top of his head, delivering dark, comedic monologues about whatever was on his mind that day. Puzzled bookstore owners didn't know what to make of the multiple requests for I, Libertine. They contacted publishers, to inquire when this novel that everyone was talking about would be released. And in this way, word of the book eventually made its way to the publisher Ian Ballantine, who traced it back to Shepherd.

Puzzled bookstore owners didn't know what to make of the multiple requests for I, Libertine. They contacted publishers, to inquire when this novel that everyone was talking about would be released. And in this way, word of the book eventually made its way to the publisher Ian Ballantine, who traced it back to Shepherd.

Comments