In the mid-1880s, Henry C. Freund showed up in New York, claiming he had invented a process that would revolutionize the sugar refining industry. He said he could refine one ton of raw sugar for 80 cents, whereas the techniques currently in use cost around $10 a ton. Plus, his method took only ten minutes, and it produced a high-quality granulated sugar, far finer than any seen before. But he insisted on keeping his process secret, disclosing only that it somehow involved electricity. On this enigmatic premise alone, he found investors willing to help him form a business, The Electric Sugar Refining Company, valued at one million dollars. But the reality was that he didn't have any secret process, let alone one involving electricity. He was simply switching raw sugar for refined sugar he had bought in stores, and then hiding the raw sugar in a secret room at his factory.

The New York Demonstrations

Details of Freund's early life are sketchy. He was probably American-born, though he passed himself off as a German chemist. Or, at least, newspapers often described him as being German, possibly because of his last name (which reporters spelled both 'Freund' or 'Friend', some commenting that they couldn't figure out which version was correct because Freund himself seemed to use both spellings.) By the time he showed up in New York City, in 1883, Freund appeared to be around 50 years old.

Freund initially approached members of the Havemeyer family, who controlled much of America's sugar refining industry. However, the Havemeyers refused to give him any money if he insisted on keeping his process a secret.

Theodore Havemeyer later recalled, "I told him that we never bought a pig in a bag, and that we must examine his method before considering whether we would adopt it. He positively refused to explain it or to give me an opportunity of seeing it, and I sent him away." Thus rebuffed, Freund sought out other investors.

Freund conducted numerous demonstrations of his sugar refining process for the benefit of potential investors. All who attended these demonstrations described them as strange affairs, more like spiritualistic seances than scientific presentations.

Freund usually held these demonstrations in the basement room of whatever house he and his wife were currently renting. (They moved frequently.) He would lead investors into the room and show them that it contained only two objects: a piece of cloth-covered machinery, sitting on a table in the middle of the room, and a barrel of raw molasses sugar.

The machine was quite small, almost toy-like in size. Freund told investors that they could walk around the machine and look at it, but he forbid them to touch it or lift the cloth. He also invited them to inspect the room to satisfy themselves that it had only one entrance, and that there was no refining mill concealed somewhere. He would thump on the floor with his foot to demonstrate there were no secret trap doors. Then Freund would ask the investors to wait outside, while he shut himself inside with his wife.

Obediently, the investors waited outside the room. Soon they would hear various banging and thumping noises coming from inside — noises that, as one reporter later described it, "suggested to their sanguine ears that the raw sugar was responding to the magic thrill of electricity and becoming seven times refined in the twinkling of an eye."

Ten minutes later, Freund would open the door and invite them back in. Triumphantly, he would show them that the barrel of raw sugar was now empty, and in its place was a corresponding amount of highly refined sugar. The quality of the sugar impressed many investors, as it appeared to be far finer than any other sugar commercially available.

The Electric Sugar Refining Company

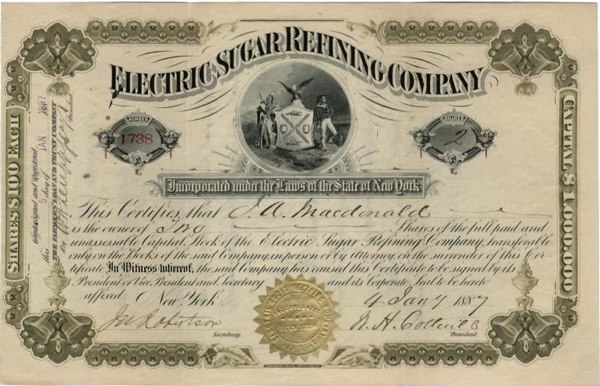

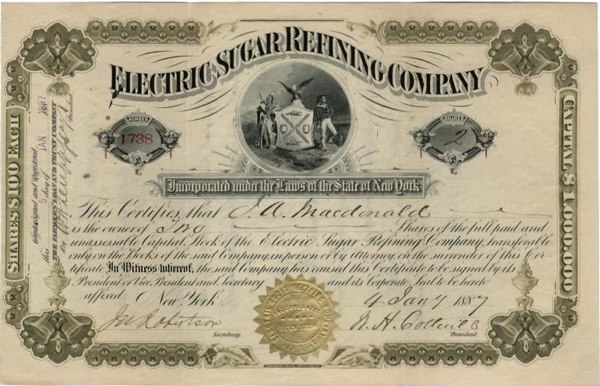

In December 1883, Freund met W.H. Cotterill, a former London solicitor. Cotterill became convinced of the value of Freund's invention, and within a year he had helped Freund form the Electric Sugar Refining Company. Cotterill served as the president of the company, while Freund continued to "experiment" with his process in order to scale it up to industrial levels of production.

The company was established with 10000 shares at a value of $100 each, for a market capitalization of one million dollars. Freund kept 6000 shares. Cotterill and other American investors controlled 1000 of them, and the remaining 3000 shares were sold in England.

Electric Sugar Refining Company stock

But despite having formed a company, Freund continued to keep his process a closely guarded secret, refusing to share it with his new investors. He explained that his process wasn't patentable, so he couldn't yet afford to let anyone but his wife know the secret. He signed a contract with the company stipulating that he would reveal his secret once a full-scale refinery was built and operational.

Meanwhile, his investors provided him with $40,000 to convert the old Atlantic Flour Mills in Brooklyn into a sugar refinery. They gave him a further $180,000 for the machinery he said he needed. Around this time, Freund began to spend lavishly. Local shopkeepers said he often flourished rolls of crisp new bills and would ask them for "change for a thousand".

Inside the new Brooklyn factory, Freund ordered the construction of two burglar-proof "secret rooms". The walls of these rooms were lined with iron and the doors had multiple locks, to which only Freund and his wife had the keys, since it was in these rooms that the secret machinery was kept.

Freund conducted a number of demonstrations at the Brooklyn factory, to satisfy his investors that good progress was being made. As in his earlier demonstrations, he would instruct people to wait outside the secret rooms while he operated his machinery. They would hear thump-bang-crunch noises from inside, and then highly refined sugar would start to flow in chutes out of the rooms into barrels.

Freund invited people to take samples of this sugar, and its quality (as well as the promise of the cheapness of its production) generated great excitement in the investment community. By 1888, the stock of the Electric Sugar Refining Company had reached as high as $625 a share in England.

The Fraud Unravels

Freund suffered from various health problems. These problems were exacerbated by his heavy drinking. So it wasn't a complete surprise when he died on March 10, 1888, just a day before a massize blizzard hit New York. He was buried during the blizzard, in a ceremony attended by only a few people.

There was later some suggestion that the directors of the Electric Sugar Refining Company tried to conceal his death, so as not to scare investors. And because almost no one witnessed the burial, there was even speculation that Freund faked his death, but those who met him when he was alive all agreed that his health had been so poor that this was highly unlikely.

After Freund's death, his wife, Olive, stepped in to take control. She was younger than he was — said to be in her early thirties and quite attractive. She assured the officers of the company that she knew her late husband's secret — and that it was also known by her stepfather and mother, Mr. and Mrs. William Howard — and that together they would be able to continue the work of completing the refinery. This satisfied the officers, who drafted a new agreement with her, stipulating they would pay her $75,000 once the refinery was complete, which was expected to be soon, and that she would then divulge the secret to them.

Olive Freund and her family lived in the Brooklyn factory for a number of months, continuing to allow no one else into the secret rooms. But they offered one reason after another for why the refinery wasn't being completed: parts were needed, or they couldn't find skilled workers. Toward the end of the year they left to live in Milan, Michigan. This made Cotterill nervous, and in December 1888 he followed them there in order to press Olive to reveal the secret.

At first Olive seemed willing to divulge the secret, in return for the $75000 promised to her. Cotterill agreed to this. But then Olive asked for an additional $5000, which Cotterill refused. The two argued. Finally, Cotterill, who had grown extremely suspicious, asked her point blank: "Does your process turn the raw sugar directly into refined sugar?" He said that if she would answer in the affirmative, he would immediately give her $2500. Instead, Olive hesitated and asked to consult privately with her lawyer.

After a while, she sent her lawyer out to Cotterill, who was waiting in an adjoining room. The lawyer asked him: "Will a process that manipulates refined sugar so that it presents the appearance of the tests you have seen be of any use to you and your company?"

"No, sir!" Cotterill replied.

The lawyer responded, "Then we advise you that you had better return to New York."

Cotterill hurried back to Brooklyn. On January 2, 1889, he and several other officers of the company broke into the secret rooms at the factory. Inside they found numerous barrels of raw sugar — all the sugar that had supposedly been converted into refined sugar during the various tests. There were also some machines for crushing cube sugar into smaller particles, but nothing else.

The method of Freund's fraud quickly became clear. He had secreted refined sugar into the factory inside boxes marked 'machinery.' He had bought this sugar in small amounts from numerous grocers in order to reduce suspicion. The raw sugar, which his process was supposed to have refined, had simply been stockpiled.

In other words, there was no electric refining process. At best, Freund may have devised a chemical method of removing impurities from already refined sugar, which allowed him to produce the highly refined sugar that so impressed investors. But this process was of little value.

When news of the fraud got out, shares of the Electric Sugar Refining Company became worthless.

Trial and Convictions

After the revelation of the fraud, some details of Freund's earlier history emerged. Reporters discovered that in 1881 he had been in Chicago, claiming to know a way to refine sugar cheaply from grapes. With the backing of investors, he had formed the Grape and Cane Sugar Refining Company. But within a year, this company collapsed after one of his investors had him arrested on a charge of obtaining money under false pretenses. However, the investor dropped the charges, and upon his release, Freund disappeared. He showed up in New York two years later.

British investors lost the most money in the Electric Sugar Refining Company, and these investors insisted that Cotterill and the other officers must have known of the fraud. But the company's officers insisted they had been deceived as much as everyone else, and no criminal charges were brought against them.

Instead, Olive Freund and her parents were arrested in Michigan and brought back to New York, where they were placed in "The Tombs," awaiting trial.

The greatest suspicion focused on Olive's stepfather, William Howard, since for the past few years he had been an active participant in Freund's demonstrations, pretending to operate the machinery. Although he put on a great display of religious piety in court, often signing hymns during breaks, the jury showed no sympathy for him and sentenced him to nine years and eight months of hard labor in Sing Sing.

Olive and her mother, by contrast, were let off almost scot free. Toward the end of 1889, the two women changed their plea from not guilty to guilty of grand larceny. In return, they were sentenced only to time already served. The District Attorney charitably reasoned that the women "undoubtedly acted under the direction of their husbands," and so couldn't be held fully to blame.

Links and References

- "Col. Fellows's Tender Heart" (Dec 12, 1889). New York Times.

- The Historic Hack House. Milan Area Historical Society.

- "Howard's Heavy Sentence" (Jun 22, 1889). New York Times: 5.

- "Keely Motor Sugar! The Electric Process an Amazing Swindle" (Jan 5, 1889). The Sun: 1.

- "Sugar Men Electrified" (Jan 5, 1889). New York Tribune: 1.

Comments