The Great Civil War Gold Hoax

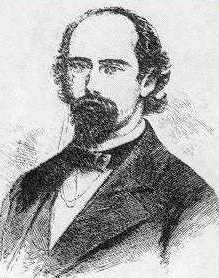

Joseph Howard, city editor of the Brooklyn Eagle. (Image from Harper's Weekly, June 4, 1864.)

But their hopes were dashed when on Wednesday May 18 they read in two of their morning papers, the New York World and the New York Journal of Commerce, that President Lincoln had issued a proclamation ordering the conscription of an additional 400,000 men into the Union army on account of "the situation in Virginia, the disaster at Red River, the delay at Charleston, and the general state of the country."

The implication of the proclamation was clear. Evidently the war was not going as well as had been hoped, thus raising the possibility that the conflict might drag on for years to come, putting further strains on the nation's economy and manpower. In reaction to this news, share prices on the New York Stock Exchange plummeted, while gold, considered to be a safe, inflation-proof investment, immediately rose in value.

After the initial shock of the news had worn off, people began to wonder why the proclamation had appeared in only two papers. By 11 o'clock on that Wednesday morning a large crowd of merchants, suspicious that the proclamation was not true, had gathered outside of the offices of the Journal of Commerce on the corner of Wall and Water Streets. Even Gen. McClellan, a presidential candidate and former commander of the Union troops, made his way to the Journal to see what was going on. The nervous editors of the paper insisted that the proclamation was true and offered as proof an Associated Press dispatch bearing the announcement that they had received earlier that morning.

However, it soon became clear that the proclamation was not real. Shortly after 11 a.m. the Associated Press issued a statement denying that they had sent such a dispatch, and at 12:30 p.m. a telegram was received from the State Department in Washington, signed by the Secretary of State, William H. Seward, declaring that the proclamation was "an absolute forgery." Word that the proclamation was bogus quickly spread throughout the city. Unfortunately, by that time the damage to stock prices had already been done.

As the dust settled the means by which the deception had been perpetrated became clear. The World and the Journal had received their information, as they received most of their information, via an Associated Press dispatch brought over from the local telegraph office by a courier (a young street urchin). The dispatch had arrived at 3:30 a.m., just after the night editors and proofreaders had gone home, leaving the night foreman at each paper as the only person responsible for reviewing the dispatch and deciding whether to insert it in the morning's edition. This moment between the departure of the night staff and the arrival of the day staff was, in fact, the only time during the entire day when a single person was responsible for reviewing incoming news. Whoever had mastermined the deception evidently knew this would be the case and had timed the arrival of the dispatch accordingly.

The night foremen on duty at the World and Journal read the dispatch, noted that it appeared to be a legitimate Associated Press dispatch, and ordered the few remaining compositors on duty to make room for it in the edition then being prepared. The papers often received telegrams very early in the morning from Washington, so there seemed to be no cause for suspicion in this case.

Other city papers had received similar dispatches. However, unlike the World and the Journal, their foremen had decided to double-check the information before printing it. They sent out messengers to nearby papers to determine if everyone had received similar dispatches (The World and the Journal happened to be fairly remote from the other papers). Learning that not every paper had received the dispatch, their suspicions were raised, and they decided not to print the proclamation until they could verify it further.

When President Lincoln learned of the false proclamation, he grew infuriated and ordered that the papers that had printed it be closed down and their proprietors arrested. Soldiers acting on his orders seized the offices of the two papers. They even seized the office of the Independent Telegraph Line, even though this business had nothing at all to do with the hoax. The ensuing furor that erupted over Lincoln's suppression of the press became one of the greatest scandals of his presidency.

In the meantime, detectives had tracked down the perpetrators of the crime. On Saturday morning, May 21, they arrested Francis A. Mallison, a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle. Mallison quickly confessed that he had been an accomplice to the crime, but claimed that Joseph Howard, Jr., the city editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, was the real mastermind behind the scheme. The detectives then arrested Howard at his residence in Brooklyn. Howard submitted quietly and later made a full confession, whereupon he was sent to Fort Lafayette.

As a newspaper man, Howard had an intimate knowledge of the news business and was therefore in a perfect position to commit such a crime. He knew that the best way to get bogus information into a paper would be by delivering it at the moment when the night foreman briefly assumed editorial control. He also knew that any word of a delay in the war effort would cause a quick rise in the price of gold. With these two pieces of information in hand, he had hatched his plan.

Howard had forged Associated Press dispatches onto which he copied his false Presidential proclamation. On Tuesday, May 17, he then invested heavily in gold. The next morning, with Mallison's help, he sent the fake dispatches through couriers to the offices of the various city papers, and when the stock market opened later that day, Howard simply waited for the bad news to hit, sold his investment, and pocketed a handsome profit.

This was actually not the first time Howard had been guilty of deception. In 1861 he had written a false story in which he claimed that Lincoln had travelled in disguise through Baltimore wearing "a Scotch cap and long military cloak" while on his way to Washington to assume the Presidency. Howard was 35 years old when he perpetrated the gold hoax. The New York Daily Tribune described him in this way: "of medium height, has dark eyes and hair, is rather bald, is pale and slender, with regular features, and wears a mustache."

Remarkably enough, Howard ended up serving less than three months of his sentence before Lincoln ordered his release on August 22, 1864. The President was apparently moved by the appeal of Henry Ward Beecher, a friend of Howard's wealthy father, who pleaded that the young man was only guilty of "the hope of making some money."

Lincoln might also have leaned towards leniency on account of the fact that Howard's false proclamation turned out to be true. On July 18, two months after the hoax, Lincoln did issue a call for more men. Howard was only wrong about the number of men. He had estimated that 400,000 would be needed, but Lincoln, in reality, asked for 500,000.

References/Further Reading:

- Wert, Jeffrey D. "The Great Civil War Gold Hoax". American History Illustrated 1980 15(1): 20-24.

- Harper's Weekly. Saturday June 4, 1864. Vol. VIII. No. 388. p.365-366.

- New York Daily Tribune. May 19-May 26, 1864.

| Main Page | Search |

Back to Gallery: 1800-1868 |