How a wealthy collector contrived to play a practical joke from the grave on the trustees of the British museum.

Francis Douce (1757-1834) was a wealthy English antiquarian, known for his collection of books, prints, drawings, coins, and artifacts. In particular he specialized in collecting material related to children's books and games, fools and jesters, as well as death, demonology, and witchcraft. He also worked briefly at the British Museum, where he held the post of Keeper of Records.

Francis Douce, portrait by James Barry

When he died in 1834, Douce left the bulk of his collection to the Bodleian Library. The gift consisted of some 15,000 books, 50,000 prints and drawings, and a large collection of coins. It was one of the library's most valuable bequests ever. However, Douce included an additional, unusual stipulation in his will. He wanted all his personal papers donated to the British Museum, but they were first to be sealed in a box and only opened sixty-six years after his death. The text of this directive was recorded in

The Gentleman's Magazine (July to December, 1834, Vol. II, New Series, p.217):

"I desire my executor to collect together all my letters and correspondence, all my private manuscripts, and unfinished or even finished essays or intended work or works, memorandum books, especially such as are marked in the inside of their covers with a red cross, with the exception only of such articles as he may think proper to destroy, as my diaries, or other articles of a merely private nature, and to put them into a strong box, to be sealed up, without lock or key, and with a brass-plate, inscribed "Mr. Douce's papers, to be opened on the 1st. of January 1900," and then to deposit this box in the British Museum, or, if the Trustees should decline receiving it, I then wish it to remain with the other things bequeathed to the Bodleian Library."

Sixty-six years is an extremely long time to make someone (even an institution) wait, and there were grumbles from scholars about the oddity of this bequest. For instance, in the August 21, 1880 edition of

Notes and Queries, one scholar wrote in with this complaint:

As Douce died in 1834, if the conditions of this bequest are literally observed, these books will have been sealed up for sixty-six years, which appears to be an unreasonable time. I am the last person in the world to disregard the wishes of testators, having left my own collections to be sealed up for twenty years; but there is a medium in all things, and, if no limit is to be observed, some literary Thellusson may order his manuscripts to be uselessly warehoused for centuries.

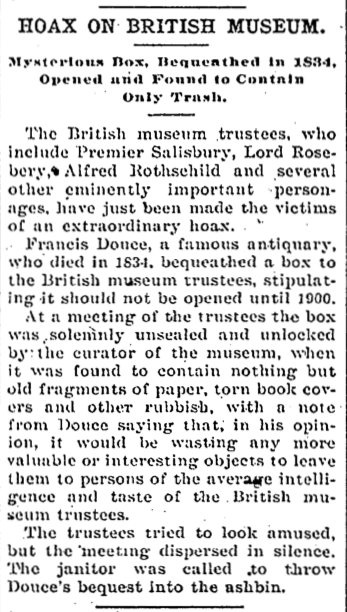

Nevertheless, the British Museum dutifully observed Douce's wishes and waited the full length of time. Finally, on January 1, 1900 the trustees of the museum gathered to open the box. There must have been some anticipation. After all, having made them wait that long, Douce must have left them something of interest.

The box was unsealed. The lid was opened, and everyone leaned over to peer inside.

There was a moment of silence as the men took in the contents of the box, and then someone snorted with disgust. Inside the box was only trash: scraps of paper and torn book covers. On top of the heap of rubbish was a note from Douce explaining that, in his opinion, it would be a waste to leave anything of greater value to the philistines at the British Museum.

It seemed that Douce had contrived to play a practical joke from the grave on the trustees of the British museum, of whom, during his life, he had a very low opinion. The trustees filed out of the room. A janitor later came and disposed of Douce's bequest.

The Dubuque Herald - May 27, 1900

Controversy: Did this really happen?

The tale of Douce's bequest makes an appealing story, especially since it fits into the ever-popular genre of jokes played upon academics, but is it true?

The broad details are correct. Douce did die in 1834 and he did leave behind his unusual bequest to the British museum. However, there is controversy over whether the box actually contained either trash or a spiteful note.

Arundell Esdaile, in

The British Museum Library: A Short History and Survey (George Allen & Unwin, 1946), suggests that the contents of Douce's box were slightly less dramatic:

By the terms of the will, the British Museum had the option to refuse the box and allow it go with the other material to the Bodleian. Instead, they kept the box and, according to Douce’s wish, did not open it until 1 January 1900, whereupon it was decided that the contents were not valuable. At the request of the Bodleian, the box was at last transferred from the British Museum to the Bodleian in 1930.

Joby Topper, who in 2002 completed his master's thesis at the University of North Carolina on Francis Douce (

Francis Douce and his Collection: An antiquarian in Great Britain, 1757-1834), suggests that it might be a case of "one's man's trash being another man's treasure." In response to an email query about the subject of Douce's bequest, Topper wrote:

The keepers of manuscripts at the British Museum (Scott and Kenyon) were not at all impressed by the unpublished manuscripts, notebooks, and letters they found in Douce's box. To my knowledge, they never made so much as a handlist of the contents. In 1930, they sent the box to the Bodleian at the Bodleian's request. There, the notebooks and correspondence were found to be very useful in understanding Douce's collection and the collecting interests of several friends, among them Isaac D'Israeli and T.F. Dibdin.

As for the insulting note, though I've never read or heard about it, I could believe that Douce was capable of writing it. He worked as Keeper of Manuscripts in the British Museum for a short time (1807-1811), and he resigned in disgust after a disagreement with the museum Trustees over the assignment of a person to his department without his approval--though later he made it very clear that he had never been happy working in the BM, and this incident was simply the last straw. Was he bitter enough to leave the BM such an insulting note? I doubt it. Surely Douce knew that his little joke would be played on innocent people of the next generation and not on the people he believed had treated him unfairly during his tenure.

However, after looking at some of the newspaper articles from 1900 (written soon after the British Museum trustees supposedly opened the box) describing Douce's practical joke, Topper professed more doubt:

It really makes me wonder if there's a nugget of truth in this story. But then again, the article was written at the height of the "yellow journalism" era, so we have good reason to be skeptical.

So ultimately it remains a mystery whether Douce actually did perpetrate an elaborate practical joke from the grave, or whether the story of his insulting bequest was an invention of either an enterprising newspaper reporter or the trustees of the British Museum.

Links and References

- Topper, Joby. (April, 2002). Francis Douce and His Collection: An Antiquarian in Great Britain, 1757-1834. A Master’s paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree.

- "Obituary -- Francis Douce, Esq. F.S.A." (Aug., 1834). The Gentleman's Magazine. Vol. 2, New Series: 212-217.

- "The Douce Bequest to the British Museum." (Aug. 21, 1880). Notes and Queries. Series 6. II: 146.

- "Hoax on British Museum." (May 27, 1900). The Dubuque Herald.

Comments