In February 1899, numerous American newspapers, including the

Los Angeles Times, printed a story claiming that a farmer, W.W. Mangum, had successfully trained monkeys to pick cotton on his plantation in Smedes, Mississippi. The story was sourced to an article in the

Cotton Planters' Journal by T.G. Lane. Reportedly Mangum was so pleased with the success of his monkey-labor experiment that he had ordered more monkeys from Africa, and he was urging other planters to join him in using simians as laborers.

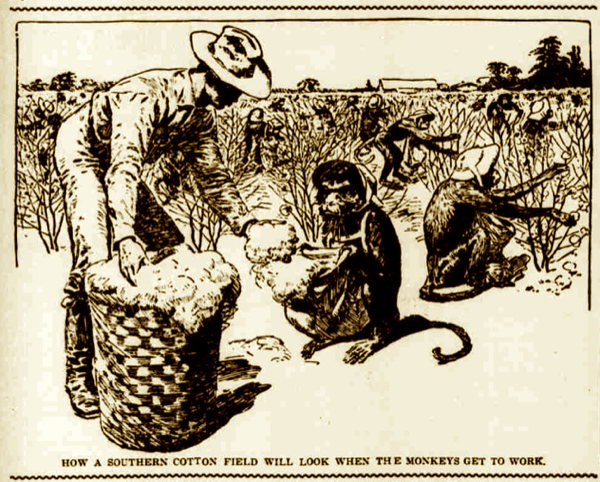

Illustration from the

Globe Republican, April 20, 1899

There's no evidence this story was true. In fact, the tale of monkeys being trained to pick cotton (or other crops) was one of the more persistent legends that circulated in the American South during the second half of the nineteenth century. Versions of it appeared in newspapers every few years.

An early version of the legend: The parable of the hidden costs of oversight

In 1867 a correspondent wrote in to the

Galveston News, claiming that eighteen years earlier, in 1849, he had attempted to train monkeys to pick cotton on his plantation in Thomas County, Georgia. He said that he had used twenty-three monkeys imported from the Island of Trinidad. Numerous papers, including the

New York Times, reprinted the text of his letter:

I was mighty well pleased when I received my monkeys. Their arrival turned my plantation topsy-turvey. For two weeks nothing was done by whites or blacks but play with the monkeys. The overseer got one of the brightest looking, and remained at his house most of the time watching the monkey's tricks, and I must confess that my wife, myself and children were in the same business. Seeing this would not pay, I began making preparations to go to work. I had reckoned on one negro managing ten monkeys, and five monkeys picking as much as three negroes.

For the next two weeks, all hands, whites and blacks were engaged in the cotton fields, teaching monkeys. The result was somewhat different from my calculations. Instead of one negro managing ten monkeys, &c;., it took ten negroes to manage one monkey, and then the monkey did not pick a pound or an ounce of cotton. I became disgusted, gave all my neighbors, that would accept, a monkey, and about a fortnight since sold the last eight to a traveling menagerie at $5 a piece. My monkey speculation has thrown me behind six weeks in cotton picking. The next time I go to Trinidad I don't believe I shall want any monkeys.

The moral of his story was that, while the monkeys had initially seemed like a good solution to the problem of harvesting cotton, supervising their work turned out to involve far more effort than it was worth.

Despite the fact that the correspondent claimed to have conducted the experiment himself, it is unlikely he actually had. An identical story had been circulating for years in parable form. The correspondent doubtless knew the parable and retold it as something that had actually happened to him, in order to make it more compelling.

For instance, in 1863 President Lincoln used the parable of the inefficient monkeys to criticize the corruption of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He said that just as "it took two overseers to watch one monkey, it needs more than one honest man to watch one Indian agent."

The May 30, 1865 issue of the

Syracuse Daily contained a letter from a correspondent who used the parable to criticize the use of African-American soldiers, suggesting that it would require numerous white soldiers to supervise every black soldier.

As late as 1889 people were still using the monkey parable. For instance, in 1889 a Texas senator used it on the floor of the Texas legislature to critique a railroad commission bill, suggesting that the state would lose money on account of the new law because the cost of its enforcement would be so high.

1887: The Simian Must Go!

In February 1887, the

Kentucky Register reported that a local farmer in Kingston had succeeded in training seven monkeys to pick hemp. While we don't have the text of the Kentucky Register's story, the article appears to have been reprinted verbatim in the

Decatur Daily Republican:

THE MISSING LINK

Monkeys To Be Trained to Do the Work of Colored Men at the South

Kingston, KY. Feb 17 -- About six months ago a brother of J.B. Parkes, who lives in Cape Town, South Africa, sent him seven large monkeys, which he told him to train to break hemp in the fields, as monkeys were used in large forces in Africa for that purpose.

Mr. Parkes almost despaired of the attempt to teach the wily little fellows the task, but after four months patient labor he has accomplished his object, and will send for ten more monkeys and train them also which will be an easy task, as the strangers will do whatever the trained ones do.

Mr. Parkes is a substantial farmer and has extensive hemp fields which the little fellows break and prepare for market, as well as negroes and white men and the cost of keeping them is very little. The seven monkeys will do as much work in one day as five of the best hemp pickers, and they seem to enjoy the work, if the chattering can be accepted as evidence.

Mr. Parkes says that the monkey can be trained to pick cotton just as well, and there is no doubt but that the day is coming when the colored man will have to seek other and advanced employment, as the monkey is bound to succeed him in time.

Versions of the article soon appeared in newspapers throughout the country, including the

New York Times which published an angry editorial denouncing Mr. Parkes's experiment. The

Times viewed monkey laborers as a new form of immigrant labor, and warned, in colorful langauge, that monkeys could soon deprive workers of the chance to earn an honest living:

"Loyal Knights of Labor should view with alarm and resist with clubs the movement to introduce imported monkey labor in this Republic... The cruel laws of political economy will favor the extension of the plan, for the cheapness of monkey labor as compared with human labor must weigh powerfully in favor of the former... If this thing is not stopped we shall presently have millions of pauper monkeys in this country, working merely for their board and lodgings and excluding an equal or greater number of Italians and Irishmen from gainful occupation. This must not be. the Simian must go...

The monkey is and must be a scab, hopeless and irreclaimable. He cannot be 'organized.' He cannot be 'called out.' He cannot be made to boycott Ehret's Beer. He is incapable of cultivating a dislike for non-union cocoanuts. He is too profoundly selfish to recognize the great principle that 'the injury of one is the concern of all.' He wears nothing but his hair, and is only in the slightest degree a consumer of the products of the toil of wage earners. he cannot be made to talk or to vote against the capitalistic skinflints. And, finally, he is a quadrumanous beast, capable in some occupations of working at the same time with all four of his hands to take the bread from the mouths of honest laborers...

A delegation of Knights of Labor should proceed at once to Kingston, where they should hang these seven scab monkeys with their own hemp, put the miserable PARKES under the ban of a perpetual boycott, and send such a letter of warning to his collusive brother in South Africa as would cause him to abandon forthwith his abhorrent industry as a monkey purveyor."

James Parkes was a real farmer living near Kingston in Madison County, Kentucky. Because of the wide dissemination of the article he began receiving hundreds of letters attacking his experiment as impractical and complaining that it would put laborers out of work. Mr. Parkes was astounded because a) he had no brother in South Africa, b) he didn't grow hemp, and c) he had no trained monkeys.

Parkes pleaded with the

Kentucky Register to publish a retraction, and eventually they did this, noting that Parkes was a modest, retiring person who deserved to be left alone.

The source of the article eventually became known when

Joseph Mulhattan, a traveling salesman, admitted he had written it. Mulhattan was a notorious hoaxer. The monkeys-pick-hemp story was only one of numerous tall tales he tricked newspapers into printing. He had simply telegraphed the article to the

Register, and they had printed it without fact-checking it in any way.

1889: Monkey Picking Cotton Statue

In November 1889, the

Galveston Daily News reported on that year's San Antonio Fair. In the center of the fair stood the exhibit of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass railway, triangular in form and about fifteen feet high. It was decorated with specimens of the game birds and ducks of the southwest, as well as samples of native products such as corn cobs, cotton, wool, fruits, and flowers. But most intriguingly, "A portion of one side is given up to a stuffed monkey picking cotton." Below the monkey statue was the inscription, "Thousands of pounds of cotton will be wasted in the fields of southwest Texas this year for want of cotton pickers -- shall we import monkeys and save our crops!"

The

Galveston News noted, "The exhibit is considered by competent judges to be as fine a thing in its line as was ever exhibited in the United States."

1899: Mister Mangum's Monkeys

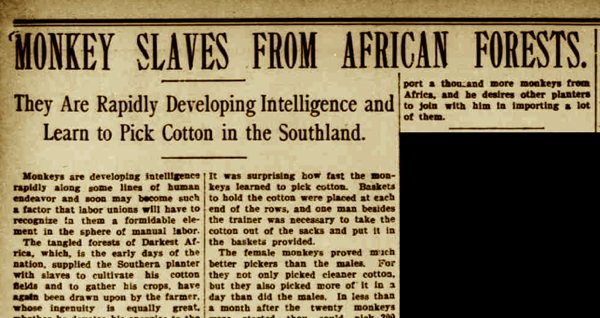

As noted in the introduction, many papers printed a version of the monkeys-pick-cotton legend in February 1899. The article described how W.W. Mangum of Smedes, Mississippi had first conducted a trial run of his idea by obtaining and training ten monkeys of the "Sphagtalis Vulgaris" breed:

Baskets to hold the cotton were placed at the end of the rows, and one man, over and above the trainer, was necessary to take the cotton out of the sacks, and put it in the baskets. The females proved much better pickers than the males, for they not only picked cleaner cotton, but they would also pick more in a day. In less than a month after the monkeys were started at the work they would pick on an average of 150 pounds a day.

This initial experiment proved such a success that in June 1898 Mangum supposedly ordered three hundred monkeys of the same breed from Africa. Eventually he succeeded in training them in the same manner as the first ten monkeys. The author of the article described visiting Mangum's plantation and seeing the monkeys work:

Headline from the

Globe Republican, April 20, 1899

I must admit that it was a glorious sight to see, and one that did my heart great good. The rows were filled with monkeys, each one with her little cotton sack around her neck, picking away quietyly and orderly, and without rush or confusion. When they got their sacks full they would run to the end of the row, where a man was stationed to empty them into the cotton baskets, when they would hurry back to their work. The monkeys seemed actually to enjoy picking.

Mangum declared his experiment to be an unqualified success, boasting that it was "the greatest discovery that has been made for the cotton planter since Whitney discovered the cotton gin."

This article, though widely disseminated, inspired skepticism. For instance, the Wisconsin

Stevens Point Journal wrote, "Monkeys may yet prove of some use outside the menagerie and hand organ business, but we have no proofs concerning the cotton pickers."

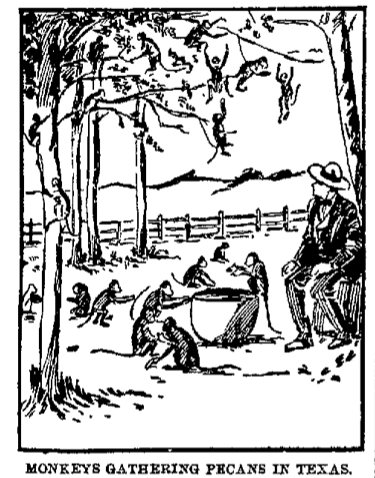

1900: Monkeys Pick Pecans

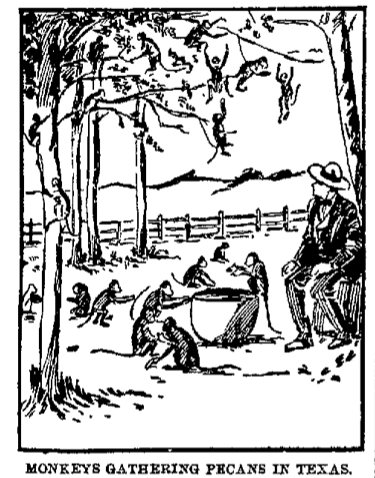

An article in the October 4, 1900 issue of the

Massillon Independent described one John Pangle of Marble Falls, Texas, who had reportedly trained monkeys to gather pecans:

Pangle insists monkeys can be trained to gather pecans. Other Texans laugh at him. Pangle has imported a big troop of simians from Brazil to save his reputation and, according to a Del Rio (Tex.) dispath to the Chicago Times-Herald, is spending hundreds of dollars to decide the issue.

Illustration from the

Masillon Independent, Oct. 4, 1900

The Meaning of the Legend

On one level, the legend of monkeys being trained to pick cotton had obvious racist overtones. The suggestion that African-American laborers, who were the backbone of the South's agricultural economy, could be easily replaced by monkeys doubtless appealed to the racism of southern whites. It was common for whites to dismissively compare black people to monkeys. (It is a widely seen psychological strategy that people symbolically reduce those they are oppressing or abusing to the status of animals, in order to justify their mistreatment.)

The tale also spoke, more broadly, to beliefs about the relationship between monkeys and mankind — particularly the belief that monkeys might be primitive humans who simply lacked adequate social training. This idea, that monkeys could be trained to become human, would later inspire experiments in the twentieth century, such as an attempt by psychologist Winthrop Kellogg in 1931 to raise a baby chimpanzee as a human.

But above all else, the tale addressed the importance of cotton to the Southern economy and how labor-intensive the harvesting of it was. Planters fantasized about finding some way to reduce the cost of harvesting the crop. For this reason, the idea of training monkeys to pick cotton proved intriguing to the Southern imagination. When the harvesting of cotton became mechanized during the twentieth century, the story lost its relevance and ceased to circulate.

Could monkeys be trained to pick cotton?

Monkeys are highly intelligent creatures, and there are credible reports of them being trained to do a wide variety of activities. For instance, in the February 7, 1919 issue of

Science, E.W. Gudger collected accounts of monkeys who had been trained to pick coconuts. Reportedly a cord was fastened round the monkey's waist, and it was then led to the coconut palm which it rapidly climbed, grabbed a coconut, and dropped it to the ground.

The problem with training monkeys to pick cotton is the repetitive nature of the task. Monkeys are wild animals. While it is possible to train them to do a single action that can be accomplished in a short span of time, they will not willingly perform a repetitive action for hours on end, day after day. Eventually their wild, untameable nature will reassert itself.

Goosing The Cotton

Weeder Geese

Although Southern farmers may not have trained monkeys to pick cotton, during the twentieth century, some cotton farmers did experiment with the use of geese to weed cotton fields. Geese would be let loose in the fields, and they would then feed on weeds growing between the cotton rows. This practice was known as "cotton goosing." In April 1963,

Time Magazine reported, "A brace of the waddling birds can keep an acre of cotton weeded; a gaggle of twelve geese can gobble as much as a hard-working man can clear with a hoe."

Cotton goosing was mainly practiced in the alluvial Mississippi Valley. Its major drawback was that the "weeder geese" trampled young cotton plants. Also, the geese frequently died from ingesting insecticides.

Links and References

- "Monkeys in the Cotton Fields." (March 24, 1867). New York Times.

- Chauncey Shafter Goodrich. (Mar. 1926). "The Legal Status of the California Indian (Concluded)." California Law Review. 14(3): 157-187.

- "Debate on the railroad commission bill continued." (Feb. 28, 1889). The Galveston Daily News.

- "Not Practicable: A Georgia Planter's Experiment." (Feb. 19, 1877). The Chicago Tribune.

- "The Missing Link." (Feb. 18, 1887). The Decatur Daily Republican.

- "Scab Monkeys." (Feb. 17, 1887). The New York Times.

- (June 25, 1887). Fort Wayne Daily Sentinel.

- Robert Grise. (Nov. 20, 2007). "Tale of the Parkes Monkey." Richmond Register.

- "Monkeys and Competition." (Aug. 9, 1899). Nebraska State Journal.

- "Monkeys Pick Cotton." (Feb. 5, 1899). Los Angeles Times.

- "The San Antonio Fair." (Nov. 10, 1889). The Galveston Daily News.

- Arthur W. Page. "a cotton harvester at last." World's Work, 21: 13, 748-60. Dec. 1910.

- "Monkeys as Laborers: How a Texas man is testing them on his farm." (Oct. 4, 1900). Massillon Independent.

- E.W. Gudger. (Feb. 7, 1919). "On monkeys trained to pick coco nuts." Science, New Series. 49(1258): 146-147.

- "Goosing the Cotton." (April 26, 1963). Time Magazine: 60.

- Charles Aiken. (1998). The Cotton Plantation South Since the Civil War. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore: 108-109.

Comments