Lord Gordon-Gordon

Lord Gordon-Gordon was the most famous alias of a nineteenth-century imposter whose specialty was posing as a wealthy Scottish landowner. He did this so well that he succeeded in convincing many people who really were wealthy to trust him with their money, which he then spent. His most famous victim was the railroad developer/robber baron Jay Gould, for which reason Gordon-Gordon is sometimes referred to as the "robber of the robber barons". The peak of Lord Gordon-Gordon's criminal career were the two years 1871 and 1872. He spent the next two years on the run, before committing suicide in 1874.

Britain

No definite facts are known about Gordon-Gordon's early life. He's rumored to have been the illegitimate child of a clergyman and parlor-maid. Various sources suggest he went by the name Hubert Hamilton, though this doubtless wasn't his real identity.

Gordon-Gordon first began passing himself off as a wealthy Scottish landowner around 1869, at which time he called himself Lord Glencairn. As part of his disguise, he employed a young valet — or a "gentleman's tiger," as such boys were called. According to the historian W.A. Croffut, Gordon-Gordon kept this boy "dressed in buckskin breeches, long boots, blue coat with gilt buttons, and an immense cockade upon his hat, which in Great Britain denotes that his master holds a commission under the sovereign."

Lord Gordon-Gordon in Scottish dress

In the character of Lord Glencairn, Gordon-Gordon struck up a friendship with a well-to-do Scottish clergyman, Mr. Simpson. Through Simpson, he was able to gain the trust of a wider network of wealthy people, as well as to establish credit with jewelers in both Edinburgh and London. His basic method-of-operation was the foot-in-the-door technique. He would make small requests of people to gain their trust, and then gradually increase the size of his requests. And having gained the trust of a person, he would use them as a reference to gain the trust of other possible victims.

Around 1870, "Lord Glencairn" disappeared, leaving behind debts of around $100,000 (the exact amount is unknown).

Minnesota

In 1871, Gordon-Gordon resurfaced in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Having shed the identity of Lord Glencairn he now called himself Lord Gordon-Gordon. He didn't brashly announce his presence, but rather let it slip very discreetly, through casual remarks, that he was the heir of the great Earls of Gordon, cousin of the Campbells, collateral relative of Lord Byron, descendant of the bold Lochinvar and the ancient kings of the Highlanders, and that he had an income of over a million dollars a year. To bolster his credibility, he deposited $40,000 in a Minneapolis bank. This was the money he had left over from his British swindle. Word of the wealthy foreigner quickly spread around Minnesota.

Croffut provides a description of Gordon-Gordon's personal appearance at this time:

"He was slender of build, about five feet ten inches in height, and dressed with the greatest care, usually wearing gloves, patent leathers and a silk hat. His hands were frequently manicured, and his hair was brushed as smooth as curly hair could be. He was clean shaven, except for two tufts of side whiskers, a l'Anglaise. He was exceedingly self-poised, calm and deliberate of speech, articulated with much precision, and posed with an amount of ceremony seldom seen on the American continent."

Gordon-Gordon made the acquaintance of Colonel John S. Loomis, Land Commissioner of the Northern Pacific Railroad, whom he informed of his interest in buying hundreds of thousands of acres of railroad land in Minnesota. He explained that he planned to resettle tenants from his overcrowded Scottish estates onto this land.

At the time, the Northern Pacific Railroad was hoping to expand westward, for which it needed to raise significant amounts of capital. So the prospect of a wealthy Scot buying up huge amounts of their land was very exciting to the railroad management, because it would provide them with the money they needed for expansion. As a result, the railroad spared no expense in wooing Lord Gordon-Gordon, in the hope of selling him land.

Colonel Loomis personally took charge of wining and dining Gordon-Gordon. He sent him on an all-expense-paid tour of the railroad lands throughout Minnesota and the Dakotas, accompanied by state officials and officers of the Railway. Gordon-Gordon requested that these men refer to him simply as "My Lord".

As he traveled across the state in first-class comfort, Gordon-Gordon periodically selected sites where he planned to build future towns or schools and then chose names for them. During this tour, the railroad provided Gordon-Gordon with a personal secretary and valet, as well as money for daily expenses. All of this reportedly cost over $45,000.

In January 1872, Gordon-Gordon finally took his leave of Minnesota, telling his hosts that he needed to travel east to arrange the transfer of money for his land purchases. His eager hosts provided him with letters of introduction to the leaders of New York society.

New York

In New York, Gordon-Gordon rented a large suite at the Astor Hotel, where he received visitors such as Horace Greeley, editor of the

New York Tribune. Through conversation with Greeley, Gordon-Gordon quickly identified a lucrative target for a new swindle — the Erie Railroad Company whose management was engaged in a bitter battle for control of the company — and he set his plan in motion.

Gordon-Gordon discreetly revealed to Greeley that he secretly owned some 60,000 shares of Erie Railroad stock and also represented certain European partners whose combined stock gave him a controlling interest in the company. He and his partners, Gordon-Gordon disclosed, planned to replace the company's Board of Directors with men more favorable to their own interests.

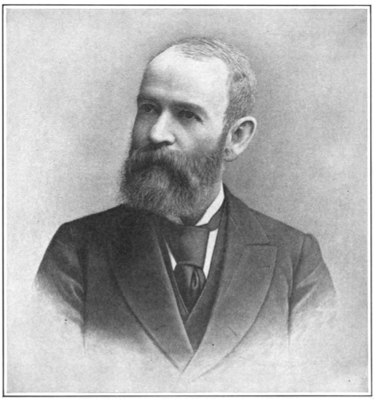

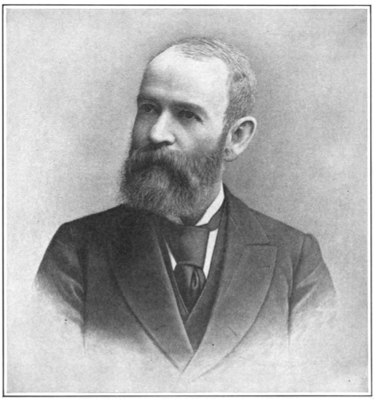

Word of this imminent management shakeup quickly spread throughout New York's business community, and caused Gordon-Gordon to receive a frantic visit from Jay Gould on March 2, 1872. Gould had himself been plotting to solidify his control over the railroad company, but he feared that this new European consortium could thwart his plans.

Jay Gould

Gould suggested that surely a deal could be struck favorable to both parties — allowing Gordon-Gordon and his partners to choose new Directors but letting Gould keep control of the company. Gordon-Gordon feigned reluctance. Why, he argued, should he trust Gould? But finally he agreed to the deal, on one condition. He insisted that Gould give him half-a-million dollars in cash and securities, as a sign of good faith. Gordon-Gordon promised not to spend this money, but rather would return it untouched once their plan had been seen through to completion. Gould promptly agreed to this condition.

Gould made good on his promise and transferred $500,000 into Gordon-Gordon's control — $160,000 in cash and the remainder in shares of various companies. At this point, Gordon-Gordon could have absconded with the cash, fled to some distant part of the world, and lived the rest of his life in comfort. But mysteriously, he didn't do this. Instead, he remained in New York and sold some of the shares.

Gould realized Gordon-Gordon was selling shares because of the trading activity on the exchange. His suspicions aroused, he immediately swung into action. Gould informed brokers not to accept the trades, and then, using Greeley as an intermediary, he informed Gordon-Gordon that their deal was off and demanded the cash and securities back.

Gordon-Gordon returned all the cash but only some of the shares (those he hadn't already sold). Gould figured there was around $150,000 in shares missing, and he concluded that Gordon-Gordon had swindled him. Gould brought suit aainst Gordon-Gordon for obtaining money under false pretenses, and he had him arrested on April 9, 1872.

To Gould's surprise, several wealthy New Yorkers (A.F. Roberts and Horace F. Clark) paid the $40,000 bond on Gordon-Gordon's behalf, allowing him to remain free during the subsequent trial.

The court proceedings soon began. On the first day of the trial, Gordon-Gordon adopted the air of an innocent man. Croffut writes:

"During three hours of vigorous examination he sat with his legs crossed and his thumbs thrust carelessly into his waistcoat pockets, as unconcerned and unruffled as if conversing in a drawing-room."

Gordon-Gordon told the court of his Scottish ancestry and also gave the names of various English nobility who, he claimed, were his friends and partners. Gordon-Gordon's willingness to supply this information seemed convincing to many of the people in the court.

That night Gould cabled the various men in Europe whom Gordon-Gordon had mentioned. All replied that they had never heard of him. Gould prepared to present this information in court the next day. But Gordon-Gordon, sensing that the game was up, had already fled on the night train to Montreal.

Canada

Gould offered a reward of $25,000 for Gordon-Gordon's arrest. He also sent detectives to Europe to investigate Gordon-Gordon's past. They soon uncovered his past alias, "Lord Glencairn," as the proprietors of the Edinburgh and London jewelry stores identified him in photographs.

For almost a year, Gordon-Gordon's whereabouts weren't known, but in the Summer of 1873 word reached the States that he was living in Fort Garry, Manitoba, just 50 miles north of Minnesota's border with Canada. Learning of this, a party of prominent Minneapolis citizens — including

Loren Fletcher,

Eugene Wilson, and

John Gilfillan, all three of whom later were elected to Congress — resolved to bring him to justice. Accompanied by several Minneapolis police officers, they crossed the border and apprehended Gordon-Gordon, whom they found sitting on his front porch.

The kidnapping party threw Gordon-Gordon into the back of a wagon and rushed back to the safety of the States. But their plan failed when they were stopped at the border by Canadian police (the kidnappers later claimed they were a few yards across the border, in U.S. territory) and thrown into jail. They sent Minneapolis Mayor George Brackett a desperate telegram: "We're in a hell of a fix; come at once!"

An international incident ensued. Minnesota papers, such as the

St. Paul Pioneer, declared that a militia should be raised to cross the border and rescue the Americans. But instead diplomatic means were used to secure their release. The negotiations eventually involved officials from the highest levels of government: Minnesota governor Horace Austin, President Ulysses Grant, and Canadian Prime Minister Sir John Macdonald. The would-be kidnappers were finally released on September 15, 1873.

Meanwhile, Gordon-Gordon was still at large, and Gould's reward offer remained in effect. But now Gordon-Gordon's pursuers made sure to go through the proper legal channels and obtained extradition papers to secure his capture. They tracked him down to a cottage in Headingly, Manitoba and sent several Toronto police officers to arrest him.

The officers arrived at the cottage on the morning of August 1, 1874 and found Gordon-Gordon asleep. When woken, Gordon-Gordon acted quite nonchalant and asked if he could finish his nap. Realizing this wasn't going to happen, he got himself dressed. He told the officers he wanted to get his cap, since it was somewhat cold outside. He then stepped into an adjoining room and shot himself in the head.

At the Coroner's subsequent inquest, Alexander Munro of the Toronto police provided the following testimony about Gordon-Gordon's final moments:

"I told Gordon that I had come to arrest him, and that I had a warrant. I showed him the warrant. He said it was all right. Just glanced over it. Don't think he read it all; and he said he was ready to go. Gave him a few minutes to put on warmer clothes. He wanted to know if I intended taking him through the States. I told him I did not. He got dressed and was all ready to go, with the exception of a Scotch cap. He called for it. He made a sort of rush into the bedroom. Where he got the revolver I do not know. I was standing in the door, within four feet of him. The next thing I saw was his turning around with his back against the wall, with the revolver in his hand. I made a rush toward him to prevent his shooting. I expected it was meant for myself, and as I was about getting hold of him, the gun went off. He made some remark while holding the revolver in his hand, but I did not catch the meaning; he sank down against the wall just as I got hold of him; I saw the blood coming out of his left ear; that was the first I noticed; afterward saw the wound in his right temple; I believe he was dying fast and was dead immediately."

Links and References

Comments